As we reported here at Bugbitten, Australia experienced the geographical expansion of the mosquito-borne Japanese Encephalitis virus in people and pigs in March and April of 2022. As of October 19, 42 human cases have been reported across 5 territories, including New South Wales, Northern Territory, Queensland, South Australia and Victoria. Unfortunately, 7 people among these cases died due to their Japanese Encephalitis infection. Because only 1 out of every 250 infections result in neurological disease, likely many more people were infected. During the same time period, Japanese Encephalitis was detected and confirmed at more than 70 piggeries across 4 territories, and twenty-six horses and an alpaca were identified as either probable or possible cases. Pigs are efficient amplification hosts for Japanese Encephalitis, while horses and alpacas, as well as people are dead-end hosts for the virus. The virus was also detected in mosquitoes collected and sentinel chickens tested in South Australia, in New South Wales, and in Victoria. This sudden geographical expansion of the virus was related to extensive flooding in southeastern Australia due to La Nina condition at the end of the Australian summer.

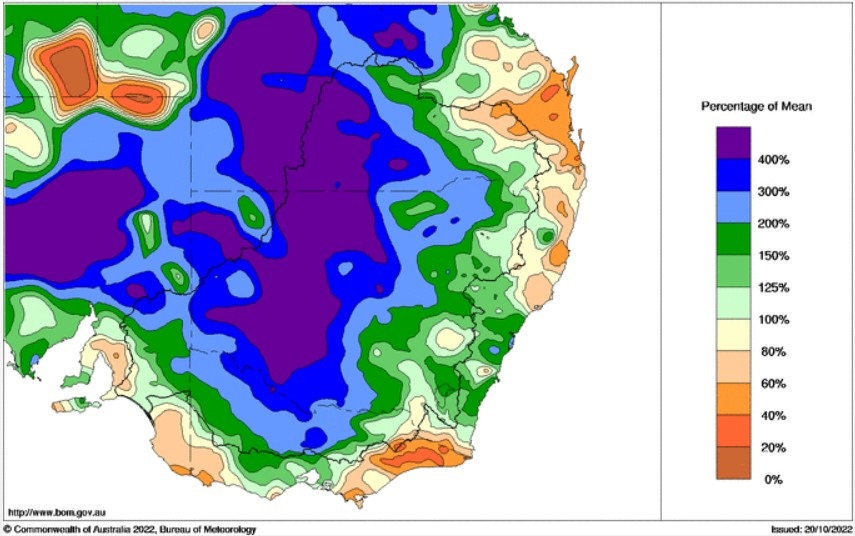

Citizens of Australia and the public health professionals tasked with protecting them were certainly hoping for climatic conditions to change coming into the new summer season, and a break in worrying about Japanese Encephalitis. Unfortunately, it looks like they will be denied that reprieve. First, the Australian Bureau of Meteorology recently announced that La Niña conditions, when the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean is cooler than average, will continue at least until early 2023. In addition, the Indian Ocean Dipole remains negative, which measures the difference in sea surface temperature between the western Indian Ocean and the eastern Indian Ocean. Under these conditions, there is likely above average rainfall over Australia, particularly in the eastern parts where the Japanese Encephalitis outbreak occurred. In addition, climate change increases the frequency of short duration, high intensity rainfall events, which lead to flash flooding. Flooding has already occurred following intense rainfall last week, and is likely to continue throughout the Australian spring and summer.

Continued wet weather is relevant for Japanese Encephalitis risk for multiple reasons. First, while mosquitoes do not emerge with Japanese Encephalitis directly from floodwaters, receding floodwaters do provide breeding sites for the most important mosquito vectors of the virus, namely Culex annulirostris. Second, floodwaters provide excellent habitat for wading birds such as herons and egrets, which are the main reservoir hosts of Japanese Encephalitis virus. The additional difficulty this upcoming season is that the virus might have overwintered in the environment, either in mosquitoes, in birds, or in pigs. If that’s the case, the virus will have a head-start as mosquitoes and waterbirds amplify it. On the other hand, JEV was only recognized late into the last mosquito season, limiting the opportunities for intervention. In this season, both public health and veterinary authorities are alert to any clinical signs in pigs, horses or humans, or detections of the virus through mosquito surveillance, and can respond quickly to emerging outbreaks. Piggeries can implement tighter biosecurity, monitor and control mosquitoes on the premises, and watch for clinical signs of Japanese Encephalitis in pigs. There are several vaccines licensed for Japanese Encephalitis in Australia, and they are recommended for people at risk of infection, such as those who work at piggeries, pork abattoirs and those conducting mosquito surveillance. A recent article published in the Journal of Clinical Diseases however suggest that perhaps more people should be included in the at-risk category. According to this article, the main vector of Japanese Encephalitis, Culex annulirostris, has an incredible average dispersal distance of more than 4 km, and more than 700,000 people live within that distance to piggeries. However, it’s unclear what the distribution of dispersal distances would be for vector mosquitoes that have ample hosts at close proximity to their breeding site, and how that would influence the actual population at risk.

Unfortunately, the current extended La Niña conditions and consequent potential Japanese Encephalitis risk might be a sign of things to come. Observations in the past 50 years have shown more frequent La Nina conditions as the planet warmed. If that trend is going to continue, it might combine with heavier precipitation and increased sea level rise to induce more frequent and severe flooding, making eastern Australia a haven for birds, mosquitoes and Japanese Encephalitis. This will necessitate an even more robust response from public health and veterinary authorities, with a combination of mosquito and viral surveillance, biosecurity and vaccination campaigns, and public outreach and education on mosquito control and personal protection measures. Let’s hope that will not be necessary!

Comments