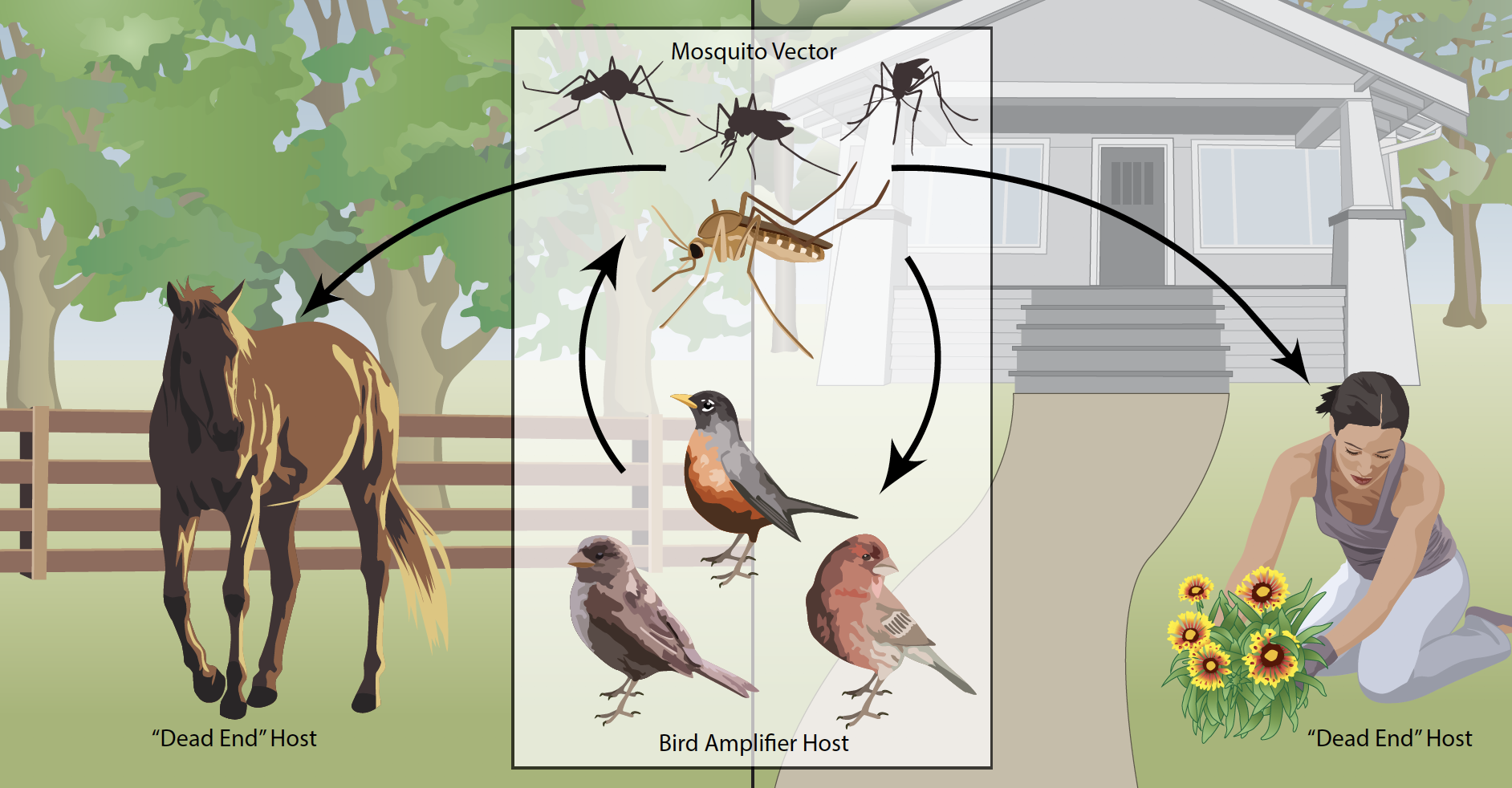

West Nile Virus causes the most common mosquito-borne human disease in the United States. Between 1999-2019, over 51,000 people contracted the virus and 2,390 deaths were recorded. The virus normally circulates in bird populations. Mammals are dead end hosts, which means they can’t pass on infections, though some, like humans, can get sick. Many different mosquitoes transmit West Nile Virus (including species in the Aedes, Anopheles and Culex genera). Because there is no cure or vaccination, reducing infectious mosquito bites, particularly in August and September, is one of the most effective forms of prevention.

However, as a zoonotic disease (transmitted from animals to humans), there are many different factors that affect where and when the virus is transmitted. West Nile Virus was first identified in Uganda in 1937 (in an area that was then called the West Nile District, hence the name). The virus was found in several crows and pigeons in the Nile Delta and wasn’t known to cause disease. However, a pathogenic strain circulating in Israel and Tunisia spread to New York, causing an outbreak that spread throughout the US. The virus can be highly pathogenic to birds in the Americas (particularly crows). Outbreaks in birds can increase risk for human spread, particularly when virus loads are very high.

A recent study looked at how nutrition impacts infection with West Nile virus. The focus of the study was on American robins (Turdus migratorius), which are common bitten by mosquitoes and can have high levels of West Nile virus during infection. Robins are also commonly found, suggesting they are important for the maintenance and spread of West Nile Virus. The scientists caught 42 robins in Michigan and slowly acclimated them to laboratory conditions before moving them to a specialist lab in New York for experimental infections.

All robins were given unlimited water and fed a fixed diet. They were first screened for previous infection with West Nile virus using a plague reduction neutralization assay that detects antibodies specific to West Nile virus. Three of the robins had antibodies and were placed in the control groups. The remainder of the naïve robins were split into one of four treatment groups:

- Normal food + infected with West Nile Virus

- Normal food + inoculated with saline

- Restricted food + infected with West Nile Virus

- Restricted food + inoculated with saline

For the two days immediately before infection, birds in the ‘restricted food’ treatment groups did not receive food, whereas the ‘normal food’ groups received the same diet. On the day of infection, all birds received the normal diet, so there were only two days of food restriction total. All birds received an inoculation on the day of infection – those in the treatment group received a non-lethal does of West Nile virus, whereas the control birds only received saline.

After inoculations, birds were monitored for viral load and antibodies up to 14 days after infection. During the first 6 days, small amounts of blood were used to measure virus load with a Vero cell plague assay. When examining the birds that had a restricted diet, they found their West Nile virus infections reached higher levels of virus and for more prolonged periods compared to birds on a regular diet. The difference was great enough, that the scientists estimated that there were 200% more infectious days for food restricted birds compared to birds fed a normal diet.

But what does this mean for the virus at the population level? Sure hungry birds may be more likely to pass on West Nile virus to a mosquito, but how important is this affect? To address this, the scientist used their experimental data to build a model. This model simulated birds and mosquitoes and showed that even a small increase in the number of birds that are food stressed can have a huge impact on the number of infected mosquitoes. Even if only 20% of birds are food stressed – this can significantly increase the number of infected mosquitoes – particularly in the late summer and early fall when transmission is greatest.

This study found that robins that missed only two days of food were much more likely to spread West Nile virus. The precise mechanisms underlying why such a short window of food restriction has such a big impact on viral dynamics is unknown, but other studies that have found similar effects of food restriction on initial infections. It is believed that initial food restriction may limit immune function – and in particular the lack of some nutrients may have a big effect on the body’s ability to fight off initial infection. This study suggests that One Health – the idea that a healthy environment and healthy animals facilitate healthy humans – is important for the control and management of West Nile virus in our changing world.

Comments