Sea lice are small marine crustaceans that are external parasites of marine fish, such as salmon and brown trout. The parasites can cause considerable damage while feeding on mucus, tissue and blood from their host. The infested fish undergo a chronic stress response, releasing cortisol and depressing their immune response making them more susceptible to infections.

The life history of a sea louse

The first two larval stages of sea lice are non-feeding, swimming forms found in the surface plankton. Once they molt to the parasitic copepodid stage they search for a host. Although not much is known about this search, it is likely that light, currents and salinity assist with chemo- and mechanosensory cues coming into play at close quarters. Copepodid stages require a salinity above 25 0/00 and migrate towards the light.

More molts occur when the larvae attach to the surface of the host, but they move freely once they are adult. The mouth parts are adapted to form a siphon and most of the body is covered by a shield that forms a suction pad to hold them in place. Females are larger than males and they produce several long egg strings during their lifetime.

Fish farms act as restaurants for sea lice

The large-scale farming of Atlantic salmon has created an abundance of hosts for sea lice, resulting in an increase in these ectoparasites and a knock-on effect on wild salmon populations.

Because aquaculture is a multimillion-dollar global industry, widely used prevention techniques are in place to minimise the impact of sea lice infestations. These include fish quarantine systems, optimizing nutrition, maintaining water quality, cleaner fish and the use of chemotherapeutants (with the resultant selection pressure for the evolution of resistance).

Prevention techniques are now emerging based on an understanding of the behaviour of salmon and sea lice.

Salmon behaviour

As with many other bony fish, salmon need to replenish the gas in their swim bladder to adjust their buoyancy. This requires them to come to the surface where they encounter sea lice larvae. Sea-caged Atlantic salmon spend a lot of time in surface waters but will swim deeper to maintain their preferred temperature of 16°C. Unexpectedly, however, Norwegian scientists have established that salmon can be kept submerged in cages for 17 days without becoming stressed and were not excessively stressed until being submerged for 4 months.

Altering salmon behaviour, by restricting the time the fish spend in the surface waters, will make it less likely that they will encounter sea lice and become infested.

New farming techniques

New salmon farming techniques have been developed that involve using novel, depth-based, fish-cage designs. These fish cages exclude the fish from surface waters and may involve deep feeding and lighting to attract the fish to the bottom of the cage.

The snorkel sea cage

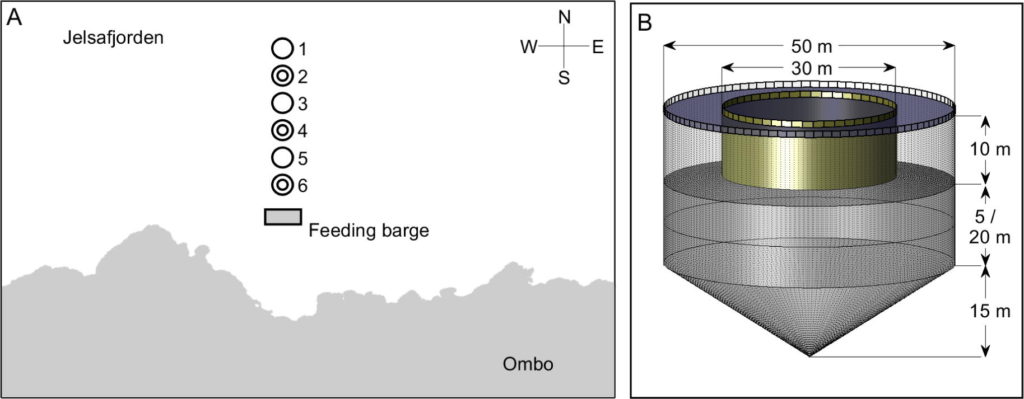

One of the new technologies is the snorkel cage. This large cage has a central tube, the snorkel, that is impenetrable to sea lice and opens at a depth below which sea lice larvae are usually found. A barrier above the snorkel entrance prevents the salmon from swimming to the surface waters unless they are in the snorkel. The technology is based on the results of several short-term research studies of efficiency and effect on fish health. For instance, a study conducted in 2016 found that sea louse infestation was reduced by over 50% when fish were kept in these cages for 12 weeks and that the confinement had no effect of fish mortality or welfare. However, there has been concern that the findings of this and other studies may not be relevant to large scale commercial aquaculture conducted over several seasons.

A long-term study

To remedy this concern, Lena Geitung and her colleagues conducted a 12-month study of salmon kept in snorkel cages at a Norwegian fish farm. The study compared louse infestation in 3 standard cages and 3 snorkel cages with a snorkel depth of 10 metres. If lice reached more than the allowable limit of infestation the cages were de-loused using hydrogen peroxide or thermolicer treatments.

The number of newly attached lice was 75% lower in the snorkel cages compared with the standard cages throughout the study period and the need to de-louse reduced by a factor of almost two.

During the year the cages are naturally exposed to brackish waters that sea lice avoid and periods of warmer temperatures that push fish downwards. Temperature and salinity were measured throughout the year in this experiment. The researchers found snorkel cages were less effective in late summer and autumn when surface water was brackish and its temperature increased. Salmon may swim in deeper waters in the standard cages at this time and, in the snorkel cages, surviving copepodids may sink to levels lower than the opening of the snorkel. Overall infestation rates in August and September were low and did not differ in the two cage types.

While effective in a long-term commercial setting, it was concluded that depth-based technologies such as snorkel cages could be abandoned during predictable periods of high temperatures and low salinity.

Comments