We live in a rhythmic world, and so do our parasites. As human beings we follow a pretty repeatable pattern every day: sleep, work, eat, repeat. As well as our behaviour, our biological processes also have repeatable patterns. We have daily rhythms in activity, body temperature, food intake, metabolism, immune function and urine production to name a few.

To know what, and when to do things each day, we take time cues from our environment, primarily using the sun. Environmental cues are used to set the timing of our internal clocks. We need these clocks for successful survival and reproduction as they allow us to coordinate our biological processes with rhythms in our environment. Parasites live in a rhythmic world inside hosts, and several recent studies have begun to discover how host rhythms affect parasites.

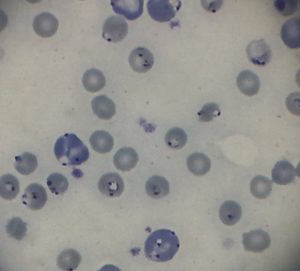

In February, we published a new study that found when hosts eat determines the timing of daily activities of their malaria parasites. Using a rodent model system, we showed that when the mice’s mealtime changed, the parasites living inside them altered the timing of when they infected red blood cells and when they undergo mitosis.

Why might eating be important?

We then did some more experiments to ask what aspect of feeding time matters. We found that increases in blood glucose concentration, associated with mealtimes, coincide with the time at which the most metabolically active and glucose hungry parasite forms are present in the blood. Parasites could be using glucose (or other things present in the host blood after eating) as a food source: When hosts eat, parasites eat.

Or parasites might be using host feeding as an environmental time cue, like we use the sun. Perhaps this enables them to avoid a rhythmic immune response, if certain parasite forms are more susceptible at certain times of day. However, by measuring host cytokines during infections as a marker of the host immune response, we were able to reveal that the parasites themselves generate a rhythmic immune response. This means that immune rhythms are a product of the parasites’ timing, not a cause of their timing.

Parasites get jet lag

Understanding what drives the timing of parasite rhythms is important. Amazingly, like us, parasites get jet lag. This reveals opportunities to reduce the severity of infection and transmission to new hosts.

A study from 2011 found that ensuring parasite mitosis and red blood cell invasion occur at the ‘correct’ time of day inside the host is crucial for a successful infection. The experiment was set up using mice in two different (opposite) light schedules: 12 hours of light followed by 12 hours of darkness, and vice versa. Parasites from mice in one light schedule were used to infect mice on the opposite light schedule. This resulted in parasites experiencing a ‘jet lag’ of 12 hours to the host environment, as mouse rhythms follow the light schedule. Doing things at the wrong time resulted in a 50% reduction in both parasite multiplication rate and the number of transmission stages produced.

This reveals the importance of timing for the survival and reproduction of malaria parasites and means that disrupting parasite rhythms could be helpful for control.

Why should we care?

We have studied malaria parasites, but rhythms matter to other parasites too, for example in transmitting to vectors. And host susceptibility to infection changes at different times of day in mice, flies and plants. Likewise, these things could apply to malaria.

With increasing reports of drug and insecticide resistance, the hunt is on to look for new cures and new ways to stop the spread of disease. Disrupting the link between eating and parasite timing – perhaps through host diet, or via drugs that manipulate the biological pathways – could reduce both the severity and spread of malaria infection. Knowing how differences in timing impact both parasites and hosts, as well as understanding the biological mechanisms controlling their rhythms, will give us the tools to be better able to tackle infection.

Comments