Heartworm disease and its spread

Q. What are we learning about the spread of heartworm disease?

Laura Kramer: Globally, the areas in which heartworm disease has become endemic are growing conduct my research in Europe, and over the past 10 years there, the disease has spread from the southern areas, including Italy, to central and eastern Europe. This was actually predicted by my University of Parma colleague Dr. Claudio Genchi, whose forecast model used meteorological data to predict where heartworm disease could be transmitted in the future.

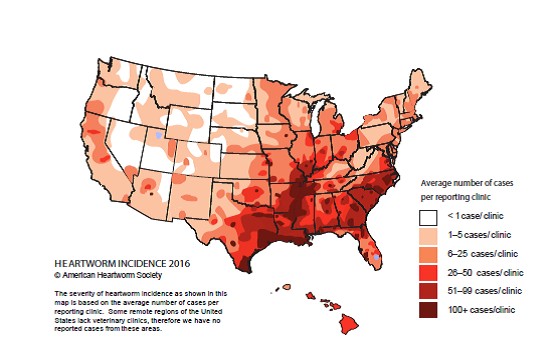

We definitely see parallels to this in what is happening in the United States. We know that climate change also is a factor here, and that infected dogs are moving around much more than they did in the past. We also know that we have new competent mosquito vectors that can transmit the disease. As a result, we’ve seen movement in the United States of heartworm infection from the South and Southeast towards the western and northern states. The bottom line: veterinarians everywhere need to be aware of the spread of heartworm disease – and that the introduction of infected dogs into a previously “non-endemic” area can present a new health risk to their patients.

For more on this topic, see the paper by Dr Claudio Genchi and Dr Laura Kramer in the Symposium Proceedings.

Q. What do we know about the mosquito vectors that spread heartworms?

Tanja McKay: A variety of mosquito species live in the United States, with 10 to 12 believed to be the major players in heartworm transmission. Each species has a different habitat, emerging from ditches, ponds or even small containers of water. Different species also have different travel patterns. Some stay near their emergence site, while others can travel as far as two miles. Some prefer the outdoors, while other mosquitoes congregate around doorways and windows in order to come inside to feed on people and pets. Understanding these interactions and ecological habits is important to understanding the transmission of heartworm.

Different species also may be active and feeding at different times of the day. Some mosquito species, such as Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti (both of which are associated with spreading the Zika virus, as well as heartworm), prefer feeding during daylight hours. Other species may be dusk or evening feeders. Knowing which mosquito species are prevalent in an area, as well as when they are active, allows the veterinarian to more accurately predict when mosquitoes in a specific locale can transmit heartworm.

Keep in mind, though, that the situation is always dynamic; the distribution of A. albopictus and A. aegypti mosquitoes, for example, was different 20 years ago than it is today. Weather patterns change and we have a mobile society, which can cause vectors and the diseases they can carry to change in a relatively short period of time.

Q. Knowing how rapidly vectors and diseases can spread to new, previously uninfected areas, what can we learn from studies on human mosquito-borne disease?

Clarke Atkins: We heard a very interesting presentation at the symposium from Dr. Audrey Odom, a pediatrician who is studying the use of breath-based diagnostics for early detection of malaria. She has learned that the Anopheles mosquito that transmits the protozoan parasite Plasmodium falciparum, is more likely to feed on malaria-infected individuals because they secrete volatile organic compounds that are known mosquito attractants. If a similar pattern were to be confirmed in animals infected with Dirofilaria immitis, this discovery might hold promise in the future for both heartworm diagnosis and intervention.

Multimodal heartworm prevention

Q. On a related topic, one of the heartworm prevention strategies discussed at the Triennial Symposium was “multimodal” prevention, which includes incorporating strategies to address the mosquito vector in preventing heartworm transmission. Can you explain?

Matthew Miller: Historically we have emphasized the use of macrocyclic lactone (ML) containing products in the prevention of heartworm infections. If we think about standard ML therapy, we are basically accepting the fact that transmission will occur, but we are going to prevent maturation of the infection. Multimodal therapy includes the use of a combination repellent/insecticide to help prevent that initial infection. At the same time, we want to make sure we have a back-up plan. Knowing that the repellent will not be 100% effective, we have an ML onboard year-round to make sure that if transmission occurs, the infection never becomes an adult heartworm infection.

Q. What are the limitations of insecticide/repellent-only therapy?

Matthew Miller: No one is recommending that mosquito-blocking therapy be used in exchange for a macrocyclic lactone (ML). It’s an add-on, and the primary means of prevention needs to be an ML. What we’re trying to do with this approach is minimize the number of bites that occur. If we simultaneously administer an ML year-round to prevent maturation of infections, that combination therapy may optimize the likelihood that we prevent transmission. In addition, if we have a dog that’s already infected and is microfilaremic, we can reduce the likelihood that a mosquito will bite that dog and serve as a vector to another patient close by.

For more on this topic, see the papers by Dr John McCall and colleagues on shifting the paradigm in heartworm prevention and blocking transmission of heartworms to mosquitoes in the Symposium Proceedings.

Heartworm diagnostics

Q. A significant amount of discussion was focused during the Triennial Symposium on the subject of heat treating blood samples to reverse false-negative results. How would you summarize the findings?

Byron Blagburn: The concept of disassociating antigens and antibodies has been around for two to three decades. At one time, heartworm tests used by veterinarians had a mandated step that was either acid – or enzyme-based in which you disassociated antibodies. However, that step was considered by some veterinarians to be too complicated, so the manufacturers eliminated it in their patient-side tests. Today our research is addressing it again because we know that some antigen blocking does occur. We don’t know if it’s the inflammation caused by heartworm or another agent – or the existence of antibodies in excessive amounts in individual pets – but we know that it occurs. And we know that by using heat, which is the topic that’s most popular now, we can disassociate those antibodies and convert those negatives to positives.

Q. How should practicing veterinarians interpret this information? Should they alter their diagnostic protocols?

Byron Blagburn: I think it’s important to note that veterinarians should not feel they need to heat-treat every sample that tests negative. However, if a practitioner suspects heartworm infection – for instance, if they see microfilariae (MF) in conjunction with a negative antigen test, or get a negative antigen test on a dog with clinical signs – those dogs are good candidates for heat treatment of their serum, with retesting for heartworm antigens.

Q. What about heat treatment of feline serum? What do we know?

Byron Blagburn: Heat treatment of feline serum in many ways may be more interesting, and the result may be more applicable. Because cats have low worm burdens and more male-only infections, they are much more likely to be antigen-negative, even when heartworm infected. Recent studies show that experimental heartworm infections in cats that test negative on this antigen test can be converted to positive with heat treatment of serum. I think the most important point about reversal with feline heartworm is that when you heat treat antibody-positive serum, you increase the number of antigen positives and there’s better correlation between antigen and antibodies.

For more on this topic, see the papers by in the Symposium Proceedings by Dr Melissa Beall and colleagues, Dr Brian DiGangi and colleagues, Dr Luigi Venco and colleagues, Dr James Carmichael and colleagues, and Dr Lindsay Starkey and colleagues.

———————————————–

See part 3 of this three-part series for Q&A on lack of efficacy and resistance to heartworm preventives and heartworm treatment protocols. You can read part 1 here.

Comments