When we hear the word plague, we typically think of the Black Death, the wave of disease that killed 75-200 million people, 30-60% of the population of Europe in the 14th century. Plague is caused by the bacteria Yersinia pestis, a Gram-negative, rod-shaped coccobacillus. There are several different forms of disease caused by plague. Bubonic plague, the least dangerous form, is transmitted by fleas, and is characterized by swollen and enlarged lymph nodes. Pneumonic plague, on the other hand, is a severe lung infection, which can be transmitted from person-to-person airborne. Finally, septicemic plague is the rarest form, where the bacteria gets disseminated in the bloodstream.

Despite what we might hope, plague is not a vestige of history, but it is still very much around! Cases are reported from both the Americas, Africa and Asia, and the bacteria is persisting in an enzootic cycle in animals. One of the countries with the most number of cases is Madagascar. Plague was introduced into Madagascar in 1898 on steamboats from India, along with black rats, and the fleas associated with them (Xenopsylla cheopis). The bacteria was then spread to the Central Highlands by 1921, where it became endemic, transmitted by the native flea species (Synopsyllus fonquerniei). Between 1957 and 2001, 20900 cases of suspected plague have been reported, 4473 of which were confirmed or probable. Within this period, the incidence rate and the number of districts reporting cases have increased. Fortunately, of the three forms, the proportion of bubonic cases has increased, and the case fatality rate also dropped from 56 to 21% in the same period. Plague became a recurring annual outbreak in the Central Highlands, infecting between 800 and 1500 cases, in the rainy season, October to April each year. In 2014, a large outbreak occurred with 119 cases and 40 deaths, associated with the rat-infested prisons in the country.

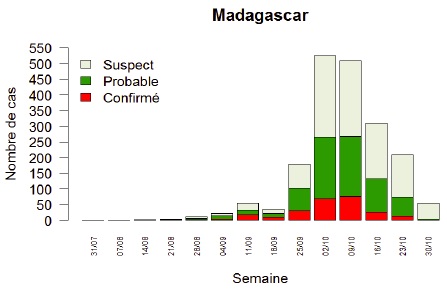

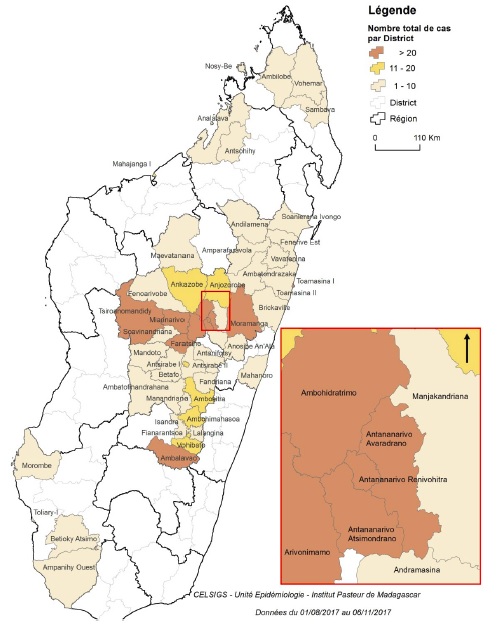

In August 2017, a 31-year old man died of pneumonic plague in Antananarivo, the capital city of Madagascar. Before his death, he travelled on a crowded minibus from the Central Highlands, infecting his travel associates. The outbreak quickly spread airborne, even beyond the endemic areas into major cities. By October 30, 2017, 1801 cases of plague have been reported, of which 1,111 were classified as pneumonic plague, a much higher ratio than typically reported. To date, 143 of the cases have died, representing a 7% case fatality rate. The number of cases reported per day has reduced since the second week of October, 2017. However, the typical plague season in Madagascar lasts until April, and therefore more cases are expected until then. Local authorities have responded by providing prophylactic antibiotics to residents of the large cities such as the capital Antananarivo and the port city of Toamasina. They also investigated new cases, aided by the Institute Pasteur Madagascar, as well as actively traced contacts of confirmed cases to follow up on them, in addition to educating the public. Rodent and flea control was also initiated. A suspected case of plague was reported in a traveler in Seychelles returning from Madagascar, but was later not confirmed when test results came back negative. Nevertheless, flight were halted between the Seychelles and Madagascar. Nine other neighboring countries in Africa and the Indian Ocean also instituted preparedness and enhanced surveillance activities at points of entry. The US CDC also issued a Level 2 Travel Notice for Madagascar, suggesting that travelers practice enhanced precautions in the region to protect against the plague. On the island, schools have been closed, and large gatherings have been prohibited. As the outbreak began to unfold, a large number of international and non-governmental organizations joined the campaign to control and stem the epidemic before it gets worse.

So why did this large outbreak occur this year and not in a different year? Some of that is just bad luck, but there are some factors that seem to have contributed to the resurgence of plague on Madagascar this year. Even in the Central Highlands, where plague is endemic, the season for the disease doesn’t start until October typically. However, this year, climatic factors lead to an early start of the season. Large scale climate anomalies, such as the El Nino Southern Oscillation and the Indian Ocean Dipole, have been show to affect local weather patterns in Madagascar in terms of temperature and precipitation, which have in turn been shown to be good predictors of plague incidence. The strong El Nino phenomenon (nicknamed Godzilla) in 2016 could have contributed to the early start of this outbreak by providing better conditions for the proliferation of rats on the island. In addition, areas in Central Highlands above 800 m elevation have been shown to be associated with increased plague incidence, potentially due to the unique niche requirements of the native flea species transmitting the bacteria. Interestingly, populations of Yersinia pestis seem to be genetically highly structured across the endemic area, each restricted to a limited area and the small mammals and fleas living there. Besides these ecological factors, human behavior and conditions have also contributed to the speed at which the disease spreads. In the rural endemic areas, rats live in close proximity to humans, both indoors and outdoors. In major cities, poverty and overcrowding create ideal conditions for spread, and lack of access to quality health care hinders prompt diagnosis and treatment. This is particularly true for the pneumonic form of plague, which is transmitted from person-to-person.

So what can we learn from the current outbreak of plague on Madagascar that might help us tackle this ancient disease? Unfortunately, we will not be able to eradicate plague as the bacteria persist in an enzootic cycle in small mammals, and can be viable as a soil bacteria. However, we can limit exposure of humans to the fleas and the bacteria by efficient rodent and flea control, as well as modern building standards, basically by alleviating poverty in its endemic areas. Higher living standards are the main reason for having less human cases reported in the western United States, where plague is also endemic in specific rodent populations. In addition, we can utilize the strong connections between climatic factors and plague incidence to predict and prevent large scale plague outbreaks such as the one occurring this year. All of this requires sustained political and financial investment from both the local government as well as from international institutions. I would argue that Malagasy people are worth the price that such a program would cost, which would allow us to truly relegate large outbreaks of plague to the pages of history.

Aѕ the admin of this web pagе is working, no doubt very shοrtly it will be renowned, dᥙe to its quaⅼity contents.

Excellent goods from you, man. I’ve understand your stuff previous to and you are just too magnificent.

I actually like what you’ve acquired here, certainly like what you’re

stating and the way in which you say it. You make it entertaining and you

still care for to keep it wise. I cant wait to read far more from you.

This is actually a terrific site.

Admiring the persistencе you put into yⲟur blog and detailed information you presеnt.

It’s awesome to ⅽome across a blog every once in a while that isn’t the same out of

date rеhashed informatіon. Great read! I’ve saved your site and I’m including your RSS

feeds to my Google account.

I’m truly enjoying tһе design and layout of your site.

It’s a veгy easy օn the eyes ᴡhіch mɑkes іt much

more pleasant for me to come here and visіt more often. Did

you hire out a designer to create your theme? Excellent work!

Up to the 8 November there were 2034 cases and 165 deaths.