On Friday, August 19, 2016, following the detection of local transmission of Zika virus on Miami Beach, the US CDC has suggested that pregnant women and their partners, if possible, should postpone any non-essential travel to any part of Miami-Dade county. For those of you not following the history of Zika virus, this relatively unknown cousin of dengue and yellow fever, only known to exist in Uganda, where it was identified in 1947, has emerged in South America in 2015, and has been spreading unabated since then on the continent. Until August 11, 45 countries and territories in the Americas (i.e. most of them) have reported local, autochtonous transmission of this mosquito-borne virus. While it usually causes a relatively mild febrile illness, the most important health concern related to Zika virus is the potential for birth defects, including microcephaly, when pregnant mothers are infected. Zika virus has also been implicated in causing Guillain-Barre syndrome in adults. In addition, recent research with mice has demonstrated the ability of this virus to damage adult neurons. The virus is capable of sexual transmission in sperm, and men with confirmed Zika virus infection are recommended to use barrier methods or abstain from sex for at least 6 month after infection, which is a concern for family planning.

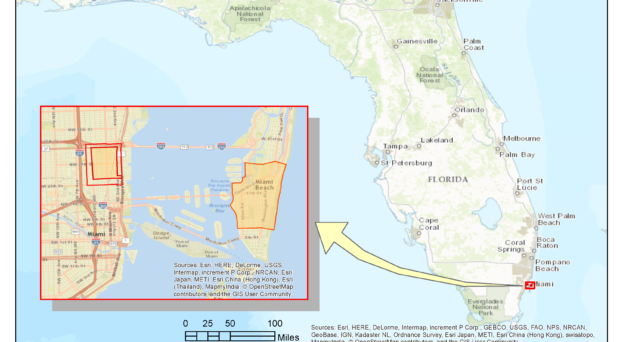

In terms of the United States, territories in the Carribean have already reported local transmission earlier during the year. In Puerto Rico alone, where Zika virus transmission is widespread, there are over 10,000 cases reported, including more than a 1,000 pregnant women. Resources to deal with the epidemic are scarce due to the ongoing fiscal crisis, and the federal government declared a public health emergency so that it can release additional funds to support the island’s response. Hawaii has so far not reported local transmission of the virus, but both it’s vectors, Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus is present on the islands, creating the potential for a local outbreak. In the continental United States, experts have long warned about the potential for localized outbreaks, and unfortunately they were proven right so far. The CDC has published maps of the estimated ranges of both vector species, which includes the entire Gulf Coast and much of the Atlantic Coast and the South-east. In addition, several statistical and mathematical models forecasted the potential risk of local virus transmission within the continental United States, with all models suggesting that Florida, especially southern Florida, as well as the Gulf Coast, are the most likely locations for local transmission to occur. Sure enough, on July 29, 2016, the Florida Department of Health reported 4 non-travel related confirmed Zika virus infections, all connected to a 1 square mile area in the popular Wynwood neighborhood in Miami. In a matter of days, the CDC sent an emergency team to assist and declared a travel advisory for pregnant women to avoid the Wynwood neighborhood, which has not happened for a US city since the polio outbreak in the US. The number of non-travel related cases continued to increase, with some of them not connected to the Wynwood neighborhood, until on August 19, the Florida Department of Health announced that they have detected a second area of active transmission in Miami Beach. The CDC expanded their travel advisory for the entire Miami-Dade county, which will likely have an effect on the $90 billion tourism industry of Florida. For pregnant women who live in the area, the CDC is recommending that they avoid mosquito bites, which translates to a near-house arrest, and is not very practical. In the meantime, the money that the state and the federal government had to scrape together for response is running out. The US Congress went on summer recess before approving any additional funding for the Zika response, even though President Obama requested an additional $1.9 billion in extra funds.

What can we expect in the near and longer term with regards to Zika virus in the continental United States? First of all, more cases, both travel-related and local transmission. Kara Dapena at the Miami Herald has created a marvelous dynamic map showing how the outbreak is developing in Florida. Dr. Henry L Niman updates a map across the US based on media reports, while the CDC and other agencies are updating their own maps based on reported cases. The Florida Department of Health is employing mosquito control to eliminate active transmission in the affected areas, including aerial spraying, with mixed results. On August 23, a non-travel related confirmed case was reported in Pinellas county, on the western side of the state, increasing the number of local cases to 41. However, since most Zika infection cases are mild, only 1 in 5 infections are likely to be reported. This means that the true number of infections at the point in Florida is somewhere around 200. According to a model recently published by Alessandro Vespigniani and Ira Longini, mosquito-borne transmission is likely to continue in Florida until October or November, and the number of confirmed cases will likely increase to around 80. We can also expect small clusters of local transmission in other Gulf states, particular Texas and Louisiana in the coming few month. This will put additional pressure on the US Congress, especially in an election year, to approve funding to help control the outbreak. This will hopefully be sufficient to accelerate the development of a Zika vaccine, especially for couples planning a family. During the fall and winter, with mosquito season ending, I expect that the anxiety will die down, and we’ll be distracted by electing the next President of the United States. However, sometime in April and May, we will be reminded of Zika virus by the pictures and sad stories of babies born with microcephaly, to mothers who were not aware that they or their fetuses were infected previously. Hopefully, by that time, we will be better prepared to protect our citizens, perhaps including the release of genetically modified mosquitoes or Wolbachia. While Neil Ferguson is probably right that in 3 years Zika virus will infect enough people in the Americas to burn itself out and disappear, I worry that Zika virus will join dengue and chikungunya as mosquito-borne diseases that we need to be concerned about, especially in Florida, California, and the Gulf States. And I don’t dare to imagine the damage that will occur in the meantime.

Comments