Warm, sunny weather drives hordes of us to the shores of lakes and rivers (when there’s no beach nearby) for a refreshing dip or a paddle. Picturesque water bodies surrounded by beautiful countryside; what could feel more natural and carefree then to cast off garments and go for a swim? But nature is in a constant state of flux and diseases you have never heard of can crop up in places even experts wouldn’t expect. This is exactly what happened recently in Corsica, France where holidaymakers and locals contracted a tropical, parasitic infection: schistosomiasis.

Outbreak in Corsica

In early 2014 the European Centre of Diseases Prevention and Control reported cases of urogenital schistosomiasis in a group of German tourists with no history of travel to schistosome-endemic countries. Further cases were reported in mainland France and pretty soon the evidence pointed to a river in Corsica as the site of infection. A rapid risk assessment for schistosomiasis in Corsica was undertaken by the ECDC calling for:

- Epidemiological investigations and molecular identification of the parasite.

- Malacological surveys to identify the local aquatic snail intermediate host species and its distribution.

- Public outreach and communication to inform the local residents and visiting tourists about schistosomiasis.

- Outreach and communication to local and European medics to improve diagnosis.

- Coordinating communication between countries and at the EU level to ensure surveillance and infection prevention.

Identifying the snail host

The causative agent of schistosomiasis is the trematode parasitic worm, Schistosoma. The current estimated number of people infected with schistosomes is over 250 million worldwide with the majority of infections in Sub-Saharan Africa. The parasite’s global distribution is limited by the distribution of the obligate intermediate snail host and by the environmental conditions conducive to infection (sanitation infrastructure, optimum temperature for infection of snail hosts, access to clean water).

Following the call from the ECDC, a study was taken to determine the epidemiology and origin of the urogenital schistosomiasis outbreak in Corisca. A European team of researchers led by Dr Jerome Boissier at the University of Perpignan, France published their findings in the Lancet in May 16.

Using holiday photos from infected tourists and local information from residents, nine potential areas of transmission were identified along the Cavu river and surveyed for aquatic snail intermediate hosts. Bulinus truncatus, a species of aquatic snails known to harbor the bovine schistosome species, occurs in parts of the Mediterranean, including Corsica. 3544 surveyed snails were identified as B. truncatus but none were found to be shedding schistosomes. This however is not unusual since previous studies in endemic countries report low prevalence of infected snails (0.5 – 3% prevalence) and there can be a strong season influence on the prevalence of shedding-snails.

To test whether these local B. truncatus snails were compatible with schistosome infections, the researchers exposed 107 locally collected snails to schistosome larvae collected from a locally infected Corsican patient. Seventeen of these snails became infected and shed cercariae.

Molecular analysis to find the parasite’s origin

Following the outbreak those patients who had acquired schistosome infections from Corsica and had no history of travel to endemic areas, were asked to provide a urine sample. The eggs were microscopically removed from the urine samples and those that were still viable were induced to hatch by placing them in water and exposing them to sunlight. Hatched schistosome larvae and non-hatched eggs were individually collected and processed for DNA work.

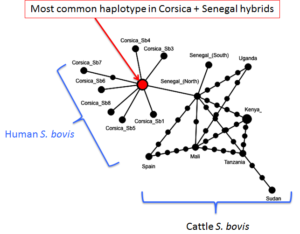

Two molecular markers (nuclear ITS and mitochondrial cox1) were used to characterize each individual schistosome using reference genetic data from the Schistosomiasis Collection at the Natural History Museum, London (SCAN) and the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the Corsican schistosomes were a mixture of Schistosoma haematobium, S. bovis and S. haematobium–S. bovis hybrids.

S. haematobium is responsible for urogenital schistosomiasis in sub-Saharan Africa whereas S. bovis is a cattle schistosome closely related to S. haematobium. Both schistosome species have been found in African B. truncatus snails and are known to hybridize. In fact phylogeographic analysis showed that the schistosomes in Corsica were most closely related to West African strains particularly from Senegal, where, as explained in a previous blog post by Elsa Leger, S. haematobium– S. bovis hybrids are prevalent. S. haematobium–S. bovis hybrids may be capable of infecting a greater range of snails as well as potentially being able to infect both humans and cattle making them a potentially zoonotic parasite.

A potential zoonosis?

Addressing the potential zoonotic aspect of the disease, cattle and goats in the Cavu river area were tested for schistosome infections using ELISA serology tests; none were found to be positive for schistosome infections. However, S. bovis in Corsica was documented in the 1960s and could potentially still be present, warranting further research.

Schistosomiasis in Europe; past present and future

The phylogeographical characterization of the schistosome species in Corsica indicates that West Africa, particularly Senegal could be the origin of the Corsican schistosome species and hybrids. There have been traditionally strong links between France and West Africa, with close connections for trade, tourism, aid and military deployment. Senegal is a popular tourist and work destination for French nationals and vice versa. Light infections with S. haematobium can be largely asymptomatic or can be misdiagnosed thus infected individuals may not know they are infected and may be introducing the parasite to suitable areas where potential intermediate host snails are present.

Currently, the ECDC is monitoring for more schistosomiasis outbreaks in southern Europe and national public health institutes are raising awareness of potential schistosomiasis transmission occurring in the Cavu River. A further case of acute schistosomiasis was reported in the summer of 2015.

Close monitoring and surveillance are crucial to prevent outbreaks but ultimately, controlling and eliminating these diseases in endemic areas is by far the most sustainable and ethical approach to mitigating the risk of tropical diseases.

A good post there with educating info on the disease, i rarely here of.