Over a third of humans worldwide are thought to be harbouring the resting stages of the parasite Toxoplasma gondii in the cells of their brains and other tissues. Infection with Toxoplasma usually goes un-noticed because no obvious symptoms occur as the immune system keeps the parasite in check. However, over the past couple of decades several psychological and neurological diseases and behavioural and personality changes have been reported to occur much more frequently in people who test positive for these parasites than those who have no sign of infection.

These include increased risk of schizophrenia, suicide and traffic and workplace accidents (the latter probably due to prolongation of reaction time). A good review can be found in Trends in Parasitology.

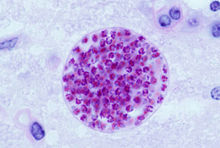

Members of the cat family are infected with Toxoplasma if they eat mice with parasite cysts in their tissue. Cats act as final hosts for the parasite, which resides in their guts and reproduces sexually to produce oocysts which are shed in cat faeces. These oocysts can survive in the environment for months.

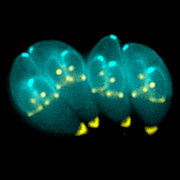

If ingested, the sporozoites that have developed in the oocysts can infect most warm-blooded animals, including pigs, sheep and cows. After first invading the cells lining the gut they multiply and spread throughout the body, eventually forming cysts, particularly in the brain and muscle tissue.

There are several routes by which humans can become infected, including ingestion of contaminated meat that is raw or lightly cooked, accidental ingestion of oocysts from contact with cats or contaminated soil or water, or in utero as parasites will pass across the placenta and infect a developing foetus if the mother is infected for the first time when pregnant. The parasites form resting cysts, particularly in the brain, that can become a latent infection that lasts a lifetime.

A new investigation

A report of a study of 358 physically healthy subjects in the USA was recently published. People were recruited through public service calls for volunteers who reported personality disorders related to psychosocial difficulties but had no evidence of psychopathology.

Given previous findings, the researchers hypothesised that evidence of T. gondii infection would be associated with a self-reported trait of aggressiveness and impulsivity in healthy individuals and be more common in those with intermittent explosive disorder (IED), a behavioural disorder in which people display explosive outbursts of anger, rage and violence that are disproportionate to the situation at hand. IED has been associated with markers of inflammation.

Study details

Data was gathered by persons with clinical psychology backgrounds that had no knowledge of the hypotheses that was being tested. Based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) structured interviews were used to identify volunteers with a set of medical signs and symptoms of anxiety, mood, substance use, impulse control, and personality disorders.

Actual aggression, aggressive tendencies and impulsivity were assessed according to established scales. Suicidal or self-harming behaviours were assessed during diagnostic interviews. Finally, anger, depression and anxiety states were monitored. Subjects with a current history of a substance use disorder or a life history of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia (or other psychotic disorder), or mental retardation were excluded from the study.

Infection was detected by measuring circulating immunoglobulin (IgG) antibodies directed against T. gondii and subjects scored according to seropositivity.

The findings

Within the study cohort a healthy control group of 110 subjects was identified as having no evidence of psychiatric diagnosis (healthy controls), an equal number met the criteria for a lifelong diagnosis of IDE and the remainder were identified as having a lifetime diagnosis of personality disorder or syndromal psychiatric disorder (psychiatric controls).

The results indicated that, overall, 15.9% of the study group were seropositive for T. gondii. The seropositive score increases from healthy controls to psychiatric controls and was highest (21.8%) in the group with IED. This group was significantly seropositive when compared with healthy controls.

People with evidence of harbouring resting stages of T. gondii had a higher aggression and impulsivity score when these factors were controlled for, but this was primarily related to aggression.

Infection did not predict a history of suicide attempt or self-injurious behaviour, contrary to previous studies relating Toxoplasma infection and suicide. The authors suggest this association was not found because the proportion of people with suicide or self-harm tendencies in this study was small or because aggression may be directed outwards rather than inwards in the two groups with psychiatric disorders in this study.

Seropositive status was also associated with lifelong history of depression and anxiety but not with substance abuse.

Various mechanisms have been suggested to explain behavioural changes associated with Toxoplasma infection in humans, mice and rats. These include the effect on neurotransmitters of the low-level immune activation in the brain that keeps the infection in check.

In summary

The once-held belief that Toxoplasma was an innocuous human parasite has long since gone. This study adds to many others that suggest that what was thought to be dormant could be stealthily manipulating the behaviour of some of its human hosts.

It is interesting to speculate that in our ancestral past we could have been manipulated by Toxoplasma such that some of the behavioural changes it induces would make us more vulnerable to predation by large felines and ensure the parasite reached its definitive host.

6 Comments