Humans have been infested with skin parasites ever since we evolved. Modern hygienic living conditions have rid many of the world’s population of lice and fleas but one group of microscopic inhabitants of human skin have not been eliminated. It appears that 100% of adult human beings worldwide are infested with these mites. Although, in most cases they cause no harm, high densities have been associated with skin conditions such as acne rosacea.

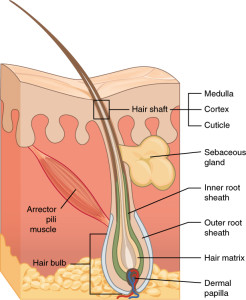

Draw your fingers across your forehead and you are likely to have captured under your nails some of the two species of microscopic mites that live in your hair follicles or sebaceous glands. They are particularly associated with eyelashes and eyebrows and are sometimes known as eyelash mites.

These mites are only 100-300uM long and have reduced legs and cylindrical bodies that are well adapted to the constricted space of their habitats; suggesting a long co-evolutionary history with mammals. Their pin-like mouth parts are used for eating dead skin cells and sebum from sebaceous glands and they come out and crawl about the skin; usually at night to avoid the light.

An ancient association

Michale Palopoli and colleagues analysed mitochondrial genome sequences from the two species of eyelash mite that live on humans and found they have an unusual mitochondrial transfer RNA (t-RNA) gene structure, with many truncated t-RNA genes. Molecular clock analyses suggested an ancient split between the two species, which last shared a common ancestor more than 87 million years ago. This indicated that their associations with man likely had different evolutionary histories. Because of their ubiquitous occurrence, these mites have proven to be useful species to provide clues concerning the coevolution of humans and their associated organisms.

The two mite species are found in different locations within the hair follicle. Demodex folliculorum lives in the hair shaft and Demodex brevis lives deep within the sebaceous glands. The group considered D. folliculorum was more likely to move easily between people due to its location near the skin surface and chose this mite for further study.

We do not know exactly how rapidly these mites transfer from human to human but studying the genetic variation and linking this to the geographic location of their host human and the host’s ancestral migrations may help to elucidate this. Easy and rapid cross infestation would dissociate particular genetic variations from family migration histories, whereas, if variations are associated with distinct geographic regions this would imply lower rates of global gene flow.

A phylogeographical approach

A recent publication from the Palopoli group describes this phylogeographical approach. They took samples from 70 people, almost all living in the USA. These people had diverse ancestries that they grouped into 4, lineages, namely; African, Asian, European and Latin American (which included South America). The mitochondrial DNA from 232 specimens of D. folliculorum mites was extracted and 241 sequences analysed.

They found high genetic diversity amongst the mite samples; suggestive of a very ancient colonisation of human beings, with no population bottlenecks in the recent past. This is despite the bottlenecks that human populations will have gone through when small groups migrated to faraway places. Four deeply divergent lineages were identified as clades A, B, C and D.

Follicle mite phylogeography

Much of the molecular variation reflected the ancestry of the mite’s hosts. People with European ancestry hosted mites that were almost entirely from clade D, whereas clade A and B mites were associated with hosts with Asian, African and Latin American ancestry. Overall ~27% of the variation in mtDNA was related to the historical geographical origin of the host; a highly significant finding.

Interestingly, mtDNA from the mites from the 7 hosts of African origin was particularly varied, with all 4 clades represented, whereas no mites from people of Asian descent were from clade C and none of those from people of Europe descent were in clades B and C. These patterns support the current thinking concerning the pattern of waves of migration out of Africa in human prehistory, with groups of our ancestors being infected with different subsets of mites and mites from some clades having been lost.

Samples from people of “Latin American” descent contained mites from all four divergent clades, probably reflecting the arrival of peoples from Africa during the slave trade as well as from migrants from Europe and N. America.

Follicle mite populations remain stable

Results from a person who was sampled several times over a 3 year period suggested mite lineages on an individual remain stable over time. This conclusion was supported by the evidence that mite populations remained similar to the host’s area of origin even years after they had moved to the USA. Finally, African Americans still contained mites from clade A (probably from African ancestors) despite close contact with those of European descent (who lack mites from clade A) for many generations.

Mites from family members were clustered in the same clades and were shown to share haplotypes, leading the authors to propose that follicle mite transmission required very close contact between hosts, not surprising considering their location within the hair follicles. They further proposed that the maintenance of mite population structure across generations may be due to variation in the particular characteristics of hair follicles that different mite clades may be adapted to (such as follicle morphology, skin hydration, hair density and lipid production) rather than very low transmission rates.

Conclusion

Phylogeographic studies of various organisms closely associated with man have confirmed theories concerning the migration patterns of early humans. Hair follicle mites are proving particularly helpful in this respect as evidence suggests they do not travel easily from person to person.

This study has provided further support for theories concerning our early history and the coevolution of these mites with humans. Present data suggest follicle mites have infected humans since their evolution and migration out of Africa.

Comments