The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a prompt laboratory confirmation for every patient with suspected malaria, either in form of microscopy or Rapid Diagnostic Tests.

Microscopy can confirm the presence of malaria parasites in the blood of a patient, identify the type of malaria and the severity of the infection. A great disadvantage of microscopy is that it requires highly trained and skilled staff. Also, the necessary equipment includes a microscope, which is costly and difficult to maintain. Moreover, results take hours.

In comparison, Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs) are cheaper and faster. The dipsticks used in RDTs present a result within a few minutes. Carrying out an RDT requires much less training than microscopy. However, just like microscopy, available RDTs necessitate the drawing of blood, which is not ideal for home usage.

Depending on blood samples has several disadvantages. If not done according to guidelines, capillary sampling can lead to bacterial contamination and infection. Pricking the skin can be painful, which may frighten especially children, who are the most vulnerable to malaria infections. Also, some people are afraid that their blood may be used in rituals.

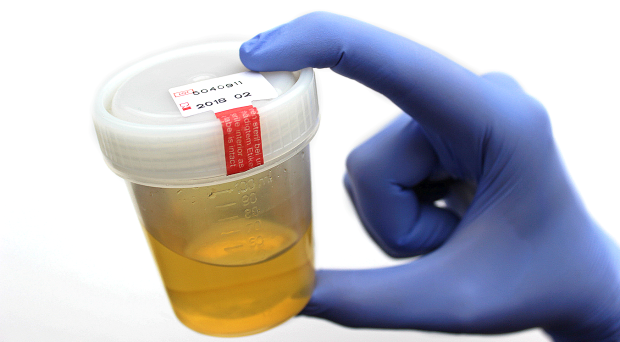

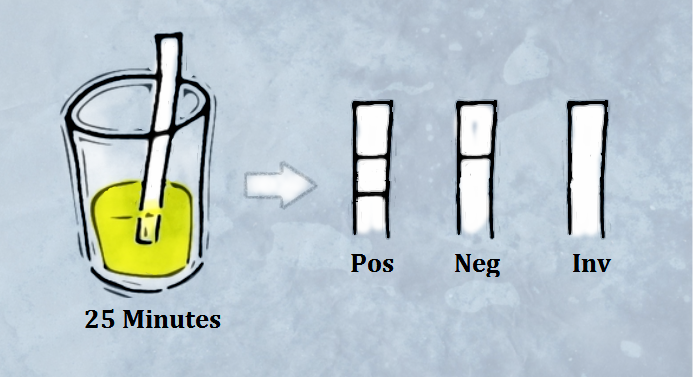

The Fyodor Urine Malaria Test, which just won the Health Innovation Challenge Awards in Nigeria, does not rely on blood and may soon enable prompt and widespread malaria testing. For the UMT, all you need to do is collect a urine sample, submerge the dipstick for 25 minutes in the urine and then count the lines that appear. Two lines confirm malaria (Pos), one line means that the patient does not have malaria (Neg) and no line means the test needs to be repeated (Inv).

Like other RDTs, the UMT detects proteins produced by the malaria parasite. Different RDTs react to different proteins, thereby detecting either just one or more types of malaria. The protein to which the UMT reacts is histidine rich protein 2 (HRP2), a protein produced by Plasmodium falciparum, which is the most common malaria species in Africa.

HRP2 is produced by merozoite and gametocyte forms of the malaria parasite. The blood then transports HRP2 to the kidneys, where it is passed on to the bladder as part of the urine. Normally, only a small amount of protein can be found in the urine, but fever and malaria both increase this amount.

Performance Studies

A study of the performance of the UMT took place between June and December 2012 in Enugu State, Nigeria, and the results were published in a paper in October 2014. A second study has just been completed, of which a few results are available online.

In the first study, the authors found a moderate concordance between the UTM and microscopy. In 83.59% of cases they investigated, the UMT and microscopic results were identical. This means almost one out of five patients received a wrong diagnosis, assuming no mistakes were made in microscopy. Sensitivity and specificity in comparison with microscopy were reported as 83.75% and 83.48% respectively. Sensitivity for samples with a parasite density not greater than 200 parasites/μl was only 50%.

HRP2-targeting RDTs, including the UMT, face possible pitfalls such as false positive results. The persistence of HRP2 following curative treatment means that a positive result may indicate a previous instead of a current infection, especially in endemic regions. Some other infections can also cause a false positive such as Schistosomiasis and Trypanosoma brucei gambiense.

A study in Kuwait showed that HRP2-targeting RDTs yielded positive results in 26% of patients who had Rheumatoid Factor, while microscopy yielded negative results. False positives were more common among patients with a high concentration of Rheumatoid Factor in their blood. However, Rheumatoid Factor does not seem to cause false positives in the UMT, as shown by the second performance study of the UMT.

A current limitation of the UMT is that it can only detect types of malaria that produce HRP2. Since P. falciparum is the only species that does so, all other types of malaria will not be detected by the UMT. Moreover, strains of P. falciparum that do not produce HRP2 have been found in Mali, Peru, India and other countries.

Prospectives

Although microscopy still seems to be the “golden standard” of laboratory malaria confirmation, the UMT has the potential to increase the number of people who will be tested for malaria within 24 hours of onset of symptoms. Being bloodless and easy to carry out, patients may even be able to test themselves at home.

Increasing the number of patients with laboratory confirmation will facilitate that each patient receives the right treatment. This will improve the outcome of febrile patients with malaria as well as those who suffer from other conditions. By reducing unnecessary use of antimalarials, the UMT may also reduce the spread of drug resistance.

3 Comments