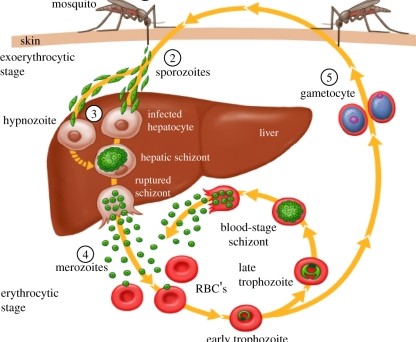

Malaria parasites undergo a complex life cycle involving six unique development stages in two organisms each generation. They sexually reproduce in mosquitoes (vectors) and asexually reproduce in vertebrate hosts. In vertebrates, the parasites enter the host when an infected mosquito injects sporozoites into the blood while feeding (Fig. 1). Sporozoites travel from capillaries into the liver of the host, where sporozoites must find and enter hepatocytes (liver cells). This is their home base within the vertebrate host and is an essential step for onward transmission. The parasites then mature into schizonts that eventually release merozoites into the bloodstream. This begins asexual reproduction in red blood cells with multiplication of parasites and differentiation into sexual stages that eventually infect mosquitoes to begin the cycle again.

The unique stages of development present an ever-changing mask for the hosts’ immune systems to recognize. Many of these have been targeted for development (annotated with numbers in Fig.1). Each stage is an essential prerequisite that eventually leads to transmission and allows for the next generation of parasites. Variation in susceptibility of a host at any stage of infection can either help or hinder parasite development. For example, humans that lack a Duffy-antigen receptor for chemokines (DARC) are less susceptible to red blood cell invasion by Plasmodium vivax merozoites. This classic example of resistance to malaria explains why Plasmodium vivax is absent from West Africa where many individuals are Duffy negative. However, until recently we didn’t know of any variation in infection susceptibility to the initial liver stage of Plasmodium.

Kaushansky and colleagues first noticed variation in the number of parasite liver stages between two strains of laboratory mice. They conducted a second study to uncover the mechanisms underlying this variation. They found evidence, through multiple study systems, that higher levels of an ephrin receptor, EphA2, was associated with increased susceptibility to malaria. First, they took mouse cell lines that varied in expression of EphA2, exposed them to sporozoites of the rodent malaria, Plasmodium yoelli, and measured how many sporozoites successfully invaded hepatocytes and how many cells were infected after 1.5 hours. This was repeated with live mice and in human cell lines with Plasmodium falciparum (a species that infects humans).

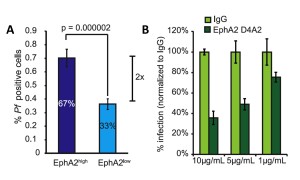

In all experiments, researchers measured the expression of EphA2 on cell surfaces and compared absolute values of EphA2 expression and grouped cells into either high or low EphA2 expression. Regardless of the methods for classifying EphA2 expression, in all systems, a higher expression of EphA2 translated to an increase in host susceptibility (Fig. 2A). This meant that both the number of sporozoites infecting each hepatocyte and the number of total cells infected were higher in cells that expressed high levels of EphA2. Subsequent experiments that examined host cell infection at a later time point (48 hours after parasite exposure) demonstrated that the increase in susceptibility persisted in cells expressing high levels of EphA2, and was even greater at later time points. This means that the expression of EphA2 may play an even greater role in the susceptibility to infection than is shown at early time points.

While it is worthwhile to note that differential expression is correlated with susceptibility, it doesn’t imply a mechanism for enhanced number and infection rates of sporozoites. EphA2 is transmembrane, meaning there are functional parts of the protein within the hepatocyte and on the surface of the cell. Using the mouse cell line, the researchers used antibodies to inhibit both domains, one set of experiments blocking extracellular EphA2 and one set blocking the kinase, intracellular domain. When EphA2 was blocked on the outside of the cell, the susceptibility of cells was reduced and in a dose dependent manner (Fig2B), whereas no significant change was observed for blocking the internal domain. This suggests that sporozoites are using the extracellular part of EphA2 to facilitate entry into the host cells.

One of the most surprising findings is the conservation of this invasion facilitation across a broad range of taxa. Plasmodium yoelli and P. falciparum are deeply diverged, meaning estimates of their most recent shared common ancestor ranges from 12 MYA (million years ago) to 64 MYA. The hosts, rodents and humans, are also distantly related. Parasites are relying on a conserved receptor across a huge range of taxa. The results provided here demonstrates that this variation in susceptibility is found across a wide host range, and utilized by a diversity of Plasmodium parasites.

The liver stage is part of malaria’s complex life cycle, and although this stage doesn’t cause clinical symptoms, reduced infection at this stage means limitations in onward transmission. Before this study, very little was known about the molecular underpinnings of invasion into hepatocytes. This study identifies an important component of hepatocyte invasion and sets up studies for future work on preventing infection with malaria at an early stage.

Comments