Zika virus, Ebola virus, and avian flu outbreaks are among the more recent and well-known international public health emergencies. It is critical to quickly control such outbreaks to minimize spreading, but often there is no standard treatment or vaccine. Therefore researchers investigating new drugs or treatments must work against the clock to discover effective treatments, without compromising ethical standards.

So how can we ease the process of ethics approval during public health emergencies? In an article recently published in BMC Medical Ethics, researchers Emilie Alirol et al. describe their experience with World Health Organization (WHO) ethics review during the recent Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa, providing recommendations to accelerate study approval in future health emergencies.

Ebola Virus Outbreak (2013-2016)

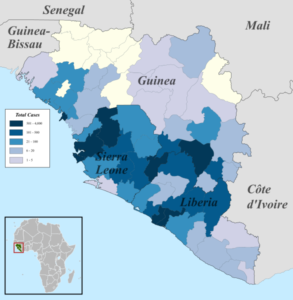

The 2013-2016 Ebola Outbreak was the largest outbreak of Ebola virus in history, and also the most deadly. With approximately 11,300 reported deaths, this outbreak killed more people than all previous outbreaks combined. At the start of the epidemic, Ebola virus research was limited to laboratory studies and data from previous outbreaks. There was no established vaccine available, and potential vaccines were still in early development. This proved especially concerning given the high mortality rate (40-90% dependent on country) and the large scale in which the disease was spreading.

Given the urgency of the outbreak, the WHO decided that use of unregistered medical interventions was acceptable, provided ethical standards were not compromised. It also allowed for a streamlined review process, with the hopes of identifying potential treatments more quickly.

Recommendations for future public health emergencies

During the outbreak, the WHO-ERC reviewed 24 new protocols and 22 amended protocols in total, including observational and interventional studies. In the article by Emilie Alirol et al., a number of approaches are proposed to help accelerate the study approval process, which are applicable to any future disease outbreaks, not just Ebola.

They found that incorrect or incomplete information was the most common hindrance of rapid ethics approval. For example, missing information on data sharing, inappropriate participant information documents, or inconsistent details like sample size. Despite time pressure, it’s recommended that documents are thoroughly reviewed to prevent unnecessary delays as these issues are avoidable.

Closer collaboration between local and international researchers may also prove effective. Studies during the Ebola outbreak were often led by international researchers, as resources were limited in locally affected areas. Local researchers have beneficial knowledge of the local culture which can be used to encourage study participation and provide advice on appropriate study plans, ultimately fast-tracking the study process.

Template agreements and joint committees

One of the more specific systems proposed includes development of template agreements for data and sample ownership and use. Many of the studies didn’t provide enough of this information which delayed approval. Because negotiating these agreements can be time consuming, the authors recommend developing template agreements which can be drafted from international consultations and discussions.

They also suggest forming a Joint Ethics Review Committee, as many trials require approval from multiple ethics committees. The joint committee would include members of committees from the countries or institutions relevant to the outbreak. Rather than waiting for approval from multiple committees, a joint committee would cut approval time while also providing the value of cross-trial data.

Participation of pregnant women and children

Arguably the most difficult proposal to implement would be the inclusion of pregnant women and children in clinical trials. In previous Ebola outbreaks, mortality rates of pregnant women were about 90%, and the highest mortality rates were in children 4 years old or younger. Given the high mortality in these groups, it makes them the most likely to benefit from a health intervention.

These rates encouraged the WHO-ERC to request protocol amendments that include children and pregnant women in studies. Despite the potential benefits, pregnant women and children were not included in any of the studies, likely due to ethical and liability concerns.

Because they are normally excluded from trials, children and pregnant women generally accept treatments based on data from other groups. In order to improve their clinical care during health emergencies, the authors of this article push for their inclusion during future outbreaks.

Preparing for future outbreaks

The issue of timeliness is one of the most challenging aspects of conducting clinical research during public health emergencies. The experience of Emilie Alirol et al. during the Ebola Outbreak displays many of the issues researchers face during such emergencies. They provide us with useful suggestions to accelerate the ethics approval process, and these should be taken into consideration in preparation for future outbreaks.

Comments