Patient preference in psychological treatment

Providing patients with choice regarding the health care they receive is actively encouraged in healthcare systems worldwide. For many patients the choice within mental health care is perceived as being limited to pharmacological versus psychological treatment, but this is certainly not the case. Providers of psychological therapies are encouraged to offer patients choice about their treatment. But does a patient’s preference for how their treatment is delivered, and whether these preferences are met, affect the outcome of the treatment?

A study published in January by Mike Crawford and colleagues, analyzed data from the National Audit of Psychological Therapies for Anxiety and Depression (NAPT), a large scale examination of the practice of psychological therapies in England and Wales which was carried out between July 2012 and January 2013. 14,587 respondents who were receiving psychological therapies in 184 NHS services were asked about their treatment preferences and the extent to which these were met by their service. They were asked about five aspects of their treatment: venue, time of day, gender of therapist, language that the treatment was delivered in, and therapy type. They were also asked to rate the extent to which they felt the therapy helped them cope with their difficulties.

The researchers found that 86% of patients expressed a preference for at least one aspect of their therapy. Out of these, almost 37% indicated that they had not been offered adequate choice, i.e. their preference had not been met. Those who had preferences for how, when and where their psychological treatment was delivered that were not met, were less likely to report that they were helped by it, suggesting that routinely assessing and meeting patient preferences may improve the outcomes of psychological treatment.

Read more about the study’s finding in this blog.

Sexual orientation and mental health

A wealth of evidence indicates that lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) populations manifest inequalities in both physical and mental health. Previous work has indicated increased risk of mental disorder symptoms, suicide and substance misuse in those that identify themselves as non-heterosexual. Despite this, sexual orientation was not recorded routinely in many population health surveys until recently.

In March, Joanna Semlyen and colleagues published research investigating the association between sexual orientation identity and poor mental health and wellbeing among adults in the UK. They used data from 12 population health surveys in the UK and conducted an individual participant meta-analysis. The data are based on a combination of home visits and telephone interviews, self-completed questionnaires and web surveys. Out of 94,818 participants, 1.1% identified as lesbian/gay; 0.9% as bisexual; and 0.8% as ‘other’.

In March, Joanna Semlyen and colleagues published research investigating the association between sexual orientation identity and poor mental health and wellbeing among adults in the UK. They used data from 12 population health surveys in the UK and conducted an individual participant meta-analysis. The data are based on a combination of home visits and telephone interviews, self-completed questionnaires and web surveys. Out of 94,818 participants, 1.1% identified as lesbian/gay; 0.9% as bisexual; and 0.8% as ‘other’.

The researchers found that adults who identify as LGB in the UK are twice as likely as heterosexual adults to suffer from anxiety or depression, although the association was different in different age groups. Adults under the age of 35 and, especially, those aged 55 and over are more vulnerable to poor mental health. Whilst the study reports an association between LGB identity and symptoms of poor mental health, it did not examine causes of these health disparities.

Co-authors Joanna Semlyen and Gareth Hagger-Johnson talk more about the study’s findings in this blog.

Crime and victimization in people with intellectual disability

An Intellectual disability is a disability which originates before the age of 18 and is characterized by significant limitations in both intellectual functioning and in adaptive behavior, interfering with everyday social and practical skills. Research suggests that people with an intellectual disability are disproportionately involved in crime both as perpetrators and victims, however due to limitations with these studies the available evidence remains far from definitive.

In May, Stuart Thomas and colleagues published a study in which they sought to determine the prevalence of criminal victimization and offending in a population with intellectual disability. The researchers employed a case linkage design using data from three databases (from disability services, public mental health services and police records) in order to analyze rates of offending and victimization in the state of Victoria, Australia; 2600 participants with an intellectual disability were compared to a community comparison group which included 4830 individuals.

The results indicated that, overall, people with intellectual disability were less likely to have an official history of victimization and were no more or less likely to have a history of criminal offending than people without intellectual disability. When the data were analyzed according to the crime level, the intellectual disability group was twice as likely to have experience violent victimization and almost six times as likely to have experienced sexual victimization, compared to the community group; they were almost more likely to have violently or sexually offended than the community group. Those with intellectual disability and a co-morbid mental illness had the highest rates of victimization and offending.

The researchers concluded that statistically speaking, people with intellectual disability are at greater risk of experiencing violent and sexual victimization and more likely to violently and sexually offend than people living in the community.

Nonmedical use of prescription drugs in the EU

Nonmedical prescription drug use typically refers to the taking of prescription drugs, whether obtained by prescription or otherwise, in a manner not intended by the prescriber or by a person for whom the drug was not prescribed; this includes the use of prescription medication to achieve euphoric states. Nonmedical prescription drug use is a major public health concern in the US, but data regarding its prevalence outside the US is limited.

In a study published in August, Scott Novak and colleagues investigated nonmedical prescription drug use in five European countries – Denmark, Germany, Spain, Sweden and the UK. The researchers analyzed data from 2,032 youths and 20,035 adults collected as part of the European Union Medicine Study, a series of parallel nationally representative surveys conducted in the five countries. Self-reported information included details on whether respondents had ever used prescription medication for euphoria or to self-treat a medical condition with medication that was not prescribed for them.

Examining three different classes of subscription drug – opioids, sedatives and stimulants – the researchers found that out of the five countries examined, Germany had the lowest levels of nonmedical prescription drug use, while the UK, Spain and Sweden had the highest levels. Having received a prescription for the particular outcome drug was associated with an elevated risk of nonmedical use. For example, receiving a prescription for a pain reliever was associated with an eight times higher risk of subsequent nonmedical use of prescription pain relievers; the risk was ten times higher for sedatives and seven times higher for stimulants. The most common sources of prescription drugs for nonmedical use were family and friends – 44% for opioids and 62% for sedatives; Internet purchases were the least common source of prescription drugs.

The researcher suggest that international collaborations are needed for continued monitoring and intervention efforts to target population subgroups at greatest risk for nonmedical prescription drug use.

Pets and the management of mental health conditions

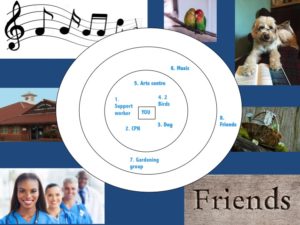

For those suffering from a long-term mental health condition the ability to manage and engage with everyday life is a key concern. Having a support network in place is often seen as key for self-management of a mental health condition. Many people consider their pets as being as important as family members, but can the companionship of a pet help with the management of a mental health condition?

In December, Helen Brooks and colleagues published their study examining the role that pets play in the management of mental health conditions; the article was a huge hit with both our readers and the public! The researchers interviewed 54 participants, 25 of whom had a pet, who were under the care of community-based mental health services and had been diagnosed with a severe mental illness. Participants were asked to rate the importance of members of their personal network including friends, family, health professionals, pets, hobbies, places, activities and objects, by placing them in a diagram of three concentric circles. Anything placed in the central circle was considered most important; the middle circle was of secondary importance and the outer circle was for those considered of lesser importance.

Pets played an important role in the social networks of people managing a long-term mental health problem, as 60% placed their pet in the central most important circle and 20% placed their pet in the second circle. Participants indicated that their pets contributed to the management of their condition in a number of ways; from developing routines that provided emotional and social support, to distraction from distressing symptoms and providing acceptance without judgment, to name but a few.

Author Helen Brooks talks more about the study’s findings in this blog; the video abstract for the article can be viewed here.

BMC Psychiatry is grateful to our editors, authors and readers for successful year and is looking forward to bringing you more exciting research in 2017. Stay tuned!

Comments