In January, England’s Chief Medical Officer, Professor Dame Sally Davies, unveiled the Government’s new alcohol guidelines.

And it’s fair to say that they received mixed reviews. Some welcomed being better informed about the health risks – including increased cancer risk – associated with drinking alcohol. Others have expressed the opinion that guidelines put the UK on the path towards becoming a ‘nanny state’.

As an organisation dedicated to beating cancer, we were in the former camp. Guidelines like these don’t tell people what to do. Instead, they offer information on how people can reduce their risk of cancer by informing them about the risks of drinking. When they were launched, we blogged about the updated guidelines, the weekly guideline of 14 units for both men and women, and how this could be useful in helping people cut their cancer risk.

But how easy is it for people to do this? And do we, as a nation, truly understand the links between alcohol and different types of cancer?

The public consultation on how the Government should communicate these guidelines closes today. And our Policy Research Centre for Cancer Prevention, an in-house research team at Cancer Research UK, working with Dr Penny Buykx’s team at the University of Sheffield’s Alcohol Research Group, have attempted to find out more about people’s awareness of the risks of alcohol.

Their latest study – carried out before the new guidelines were in place – reveals some worrying gaps in public awareness of alcohol’s harms and people’s knowledge of guidelines.

The headline figure shows that almost nine in 10 people don’t link alcohol to an increased risk of cancer. And if we dig a bit deeper, an even more worrying gap emerges.

Alcohol and cancer

We’ve written a lot about the link between alcohol and cancer – from discussing the evidence that it causes cancer, to talking about how drinking less reduces your risk of developing the disease.

When it comes to the science of how and why alcohol causes cancer, the picture isn’t too clear. But there are a few leading theories, which we blogged about recently.

Regardless of the underlying mechanism, we know that 12,800 cases of cancer are linked to alcohol each year in the UK.

To find out how much the public knows about the link, we worked with Dr Buykx’s team to survey 2,100 people in England, asking questions about their knowledge and use of alcohol guidelines – as well as their awareness of which health conditions are linked to alcohol.

Public misconceptions of alcohol and cancer

When our study participants were asked to name health conditions linked to drinking too much alcohol, only 13 per cent mentioned cancer. They were then shown a list of health conditions and asked to name those that could be caused by drinking too much alcohol. Almost half (47 per cent) selected cancer. But this is still a low level of awareness compared to 95 per cent who selected liver disease, and 59 per cent who selected diabetes. A large proportion (84 per cent) also recognised that alcohol can cause obesity and excess body weight.

But people were even more unsure when asked which types of cancer are linked to alcohol, and at what level drinking alcohol increases the risk of these cancers.

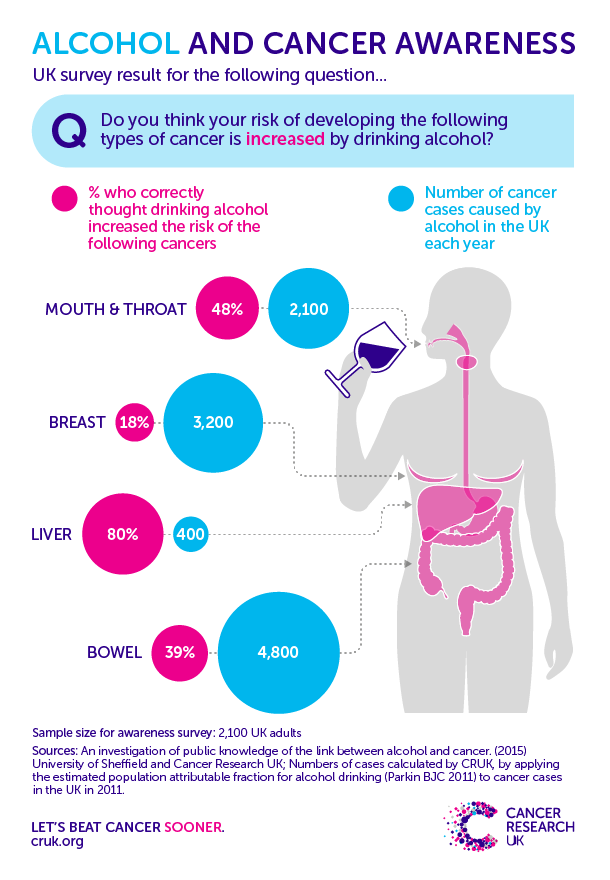

In the study, people were asked which of seven different types of cancer they thought were linked to alcohol. Of these seven cancers, four are linked to drinking (bowel, breast, mouth and throat, and liver) and three are not (brain, bladder and ovarian). The graphic below shows that awareness of the risk – or lack of risk – varied a fair bit. For example, only 18 per cent of people questioned correctly answered that breast cancer was linked to alcohol.

Each year in the UK, alcohol causes 3,200 cases of breast cancer, the second largest amount after bowel cancer, with 4,800 cases down to alcohol each year. Yet only around four in 10 people (40 per cent) linked alcohol with bowel cancer, and just under half with mouth and throat cancers.

Conversely, over half believed that bladder cancer was linked to alcohol, when research hasn’t actually found a link.

Next, the participants were asked at what level of drinking they thought a person’s risk of developing cancer starts to increase for each type. While eight in 10 people (80 per cent) had correctly said that liver cancer was linked to drinking alcohol, the majority thought this was linked to lower levels of drinking than appears to be the case.

In the UK, around 400 cases of liver cancer are linked to alcohol each year (for context, there are nearly 5,500 cases each year overall). High levels of drinking are thought to trigger liver cancer because this causes conditions – such as cirrhosis – that damage the liver’s ability to repair itself.

Public knowledge of alcohol guidelines

Taken together, these results suggest that the public may not be too well informed about the health risks associated with drinking alcohol. If this is the case, simply offering new guidelines on drinking isn’t going to be enough to help people to understand the health risks.

But they are a good place to start. It’s the duty of the government to inform the public of health risks, and provide these guidelines to help people make decisions about their own health.

The new guidelines are clear that there is no safe level of drinking when it comes to cancer risk. But our study suggests that awareness of the risks needs to improve if the guidelines are going to have the desired effect.

Until the recent announcement, the government’s alcohol guidelines had not been reviewed since 1995.

Our survey reveals that even though the guidelines haven’t changed in 20 years, only one in 10 men and one in seven women could correctly identify the guidelines for their own gender, and reported using this sometimes to keep track of their own drinking.

Now that the guidelines have changed to 14 units per week for both men and women, can we expect the public to know what they are? Our survey suggests that, without further work, this is unlikely.

So it’s important we – and others – continue to raise awareness of the health risks of drinking alcohol, and especially the links to cancer.

By helping people understand the guidelines, we hope that people will feel they have the information they need to make decisions about when they choose to drink, and how much. And that ultimately this will lead to a healthier nation.

Comments