Obesity and related non-communicable disease such as diabetes, heart disease and cancer poses a significant health, social and economic burden in countries worldwide, including the United Kingdom. Whilst the need for action is clear, the nutrition policy response is a highly controversial topic. Professor Jebb raised the question of how best to achieve dietary change: through ‘knowledge, nudge or nanny’?

Education regarding healthy nutrition is an important strategy, but insufficient. People are notoriously bad at putting their knowledge to work. The inclination to overemphasise the importance of knowledge, whilst ignoring the influence of environmental factors on human behaviours, is termed the ‘fundamental attribution error’. Education may also contribute to widening inequities.

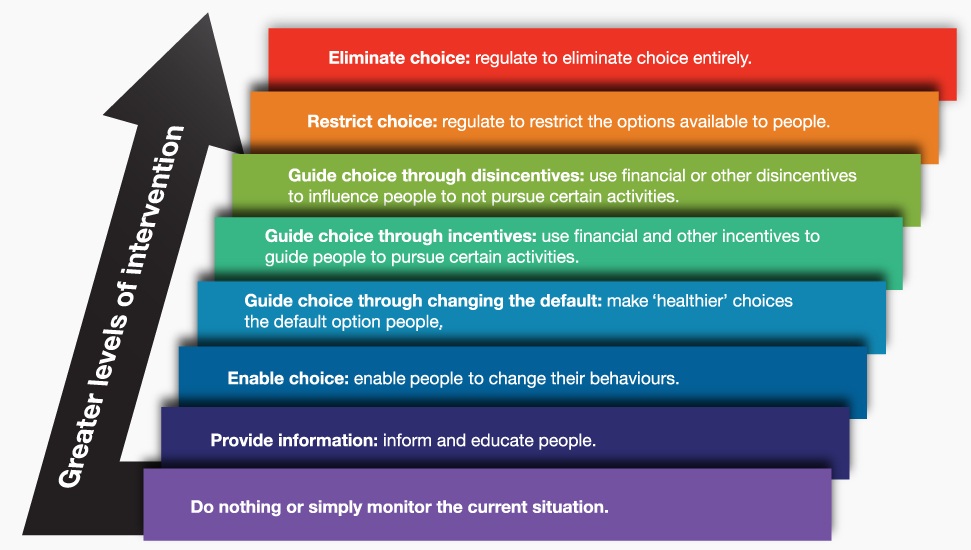

Our choices are strongly shaped by the environments in which we live. So if ‘knowledge’ is not enough, what sort of interventions are appropriate? This raises questions regarding individual choice and the role of government. Here, Professor Jebb introduced the Nuffield Intervention Ladder.

The Nuffield Intervention Ladder or what I will refer to as ‘the ladder’ describes intervention types from least to most intrusive on personal choice. With addressing diets and obesity, Professor Jebb believes we need a range of policy types, across the range of rungs on the ladder.

Less intrusive measures on the ladder could include provision of information about healthy and unhealthy foods, and provision of nutritional information on products (which helps knowledge be put into action). More effective than labelling is the signposting of healthier choices.

Taking a few steps up the ladder brings in ‘nudge’, a concept from behavioural economics. A nudge is any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behaviour in a predictable way without forbidding options or significantly changing economic incentives. Nudges are not mandates. Putting fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not.

Nudges are not mandates. Putting fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not.

The in-store environment has a huge influence over our choices, and many nudge options would fit here. For example, gondalar-end (end of aisle) promotions create a huge up-lift in sales. Removing unhealthy products from this position could make a considerable difference to the contents of supermarket baskets.

Nudge could be used to assist people make better nutritional choices, but it’s also unlikely to be enough. We celebrate the achievement we have made with tobacco control policies and smoking reduction. Here, we use a range of intervention types, including many legislative measures – the ‘nanny’ aspect of the title of this presentation.

Addressing diets and obesity will also require more direct and intrusive legislation than we have at present. This involves accepting government setting some regulation on our behalf, when consistent with population health goals, and to address a situation otherwise often beyond our (and out of) control. There is increasing public support for such measures.

Planning rules are needed to control the density of fast food outlets. Schools should be considered a special place where children deserve extra protection – a setting warranting intervention from the top of the ladder.

Product reformulation is also important. There are limits to what reformulation can technically achieve given consideration of palatability to consumers, but legislation in this area would create a level playing field for business. It would assist both business and health. A global agenda would mean product changes would not be confined to individual country markets.

Taxation, an established part of tobacco and alcohol policies, is also likely to be important. Here, sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) are an easily defined category with clear public health harms.

With tobacco, we also provide treatment options to support individuals change their behaviour and avoid tobacco-related ill health. We should also provide treatment to those already affected by obesity.

There is considerable pessimism regarding the long-term effectiveness of weight loss programmes, bariatric surgery aside. However Professor Jebb presented evidence suggesting effectiveness of some behavioural interventions. She suggests the challenge is the delivery of this type of intervention in routine care.

As a society, we are condoning a food system that promotes unhealthy food whilst wanting healthy outcomes. Are we prepared to compromise commercial freedoms to benefit wider society? Can we accept government regulation addressing food on our behalf? – especially when consistent with our population goals, and to address an out-of-control obesity situation?

We already accept such legislation with tobacco control and in many other areas. We need to take similar regulatory measures with food if we are serious about improving population diet.

Recently published related articles in BMC Obesity:

“The effect of menu labeling with calories and exercise equivalents on food selection and consumption” by Charles Platkin and colleagues.

“The correlation between supermarket size and national obesity prevalence” by Adrian Cameron and colleagues.

“A conceptual classification of parents’ attributions of the role of food advertising in children’s diets” by Simone Pettigrew and colleagues.

I agree that a more involved approach should be considered. It was once argued that lack of information was the reason people didn’t eat well, but this is just ridiculous in our current connected society. There are a million healthy eating websites out there, see: https://makeyourbodywork.com/best-healthy-food-blogs/ that teach people how to buy, prepare, and eat health meals. The information is completely available to anyone who is interested in taking and using it.

The fact is, healthy food just isn’t as easy or tasty (at least to some people) as junk food. People will always reach for a bag of chips until there is an economic reason suggesting they do otherwise.

Great article will like to contribute. Growing up in generation Y and constantly being ridiculed by older generations of our laziness, our entitlements, and our narcissism, it is reassuring to see that people are shedding light on other factors (or people) that affect childhood obesity. For 40 hours a week, children are surrounded by teachers in a school setting. This means that the majority of their weeks are molded by the direction of people other than his/her parents. Teachers, staff members, education boards, and political figures need to shape the education system towards a healthier lifestyle, whether that’s a longer recess, healthier meal options, or nutrition courses, it is nice to hear that people are taking responsibility for their roles in children’s life.

A healthy life style can be related to language; it is easier to learn and instill when someone is young, and harder to learn later on in life.

We need to watch our diet and exercise to avoid this menace of obesity and non-communicable diseases.