Ever since seeing this amazing computer reconstruction of moas on David Attenborough’s Life of Birds, I’ve been slightly obsessed by them. These giant birds seem to have died out in around 1400, hunted to extinction by the Maori who arrived on the island about a century before. There have been the odd unsubstantiated report of sightings, but I do suspect if there were six foot tall carnivorous birds running around New Zealand, we’d probably know about it. Attenborough’s computer reconstruction seems to be the nearest we’re likely to get to get to seeing these creatures.

on David Attenborough’s Life of Birds, I’ve been slightly obsessed by them. These giant birds seem to have died out in around 1400, hunted to extinction by the Maori who arrived on the island about a century before. There have been the odd unsubstantiated report of sightings, but I do suspect if there were six foot tall carnivorous birds running around New Zealand, we’d probably know about it. Attenborough’s computer reconstruction seems to be the nearest we’re likely to get to get to seeing these creatures.

But that hasn’t stopped scientists from finding out as much as they can, from the few moa bones we have. A new study in BMC Evolutionary Biology describes the exciting reconstruction of a gene controlling a feature unique to moa – these birds didn’t have any wings.

But before I get onto that, a little more history.

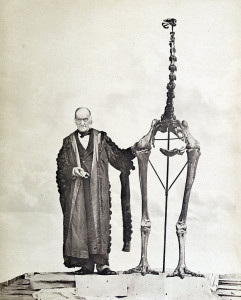

Aside from the Maori, no one knew about the existence of these weird birds until in 1839, Richard Owen, founder of the Natural History Museum, was sent moa bone by a flax trader with an enthusiasm for archaeology. Owen hypothesised it belonged to a large bird, since it was huge, but honeycombed, a common characteristic of bird bones. This theory wasn’t believed until many more bones were found and the skeleton was slowly pieced together. This picture of Owen shows him standing next to the huge skeleton, which is now back on display in the museum.

So everything we know about them in modern science is conjecture from analysis of their bones and, more recently, analysis of genetic samples from those bones. The authors of this newest study have not just analysed those genes, but reconstructed them, and shown that they still work in modern mammals. It’s as close as we’re likely to get any time soon to seeing these incredible creatures in real life, though efforts at ‘de-extinction’ of lost species are getting ever closer to success.

The scientists identified that a single gene, tbx5, controls forelimb growth, and it’s this gene in moa species that made them wingless. They then reconstructed the moa gene using PCR techniques, and inserted it into the genomes of chicken embryos in the region controlling hindlimb development. The embryos that formed (they were not allowed to develop past a specific stage around 14 days), showed reduced hindlimb development, suggesting that the moa gene that prevented the growth of limbs is very similar to the version in modern birds.

There are lots of interesting implications for this in the field of de-extinction, an area which is growing in scope thanks to genetic advances, and of course the investment of a lot of money from public and private sources.

But for now, if you want to come face to beak with these amazing things, you’ll have to make do with one of the full skeletons on display in museums, or Attenborough’s amazing computer generated moa.

- Make your mealtimes more tasteful - 20th June 2014

- Walking, but not flying, with moas - 15th May 2014

- The world's largest sequenced genome is just the start - 20th March 2014

Comments