Invasive species are often assumed to be able to easily invade any novel environment. But what occurs when the novel environment is too unsuitable and prevents the invasion?

Invaded environments may show biotic resistance, in which some biotic interactions with native species, such as competition and predation, are an impassable barrier for invasive species. Other interactions between invasive and native species could arise that would be opposite to biotic resistance.

Thus, some native species may facilitate the establishment of invasive species in recipient communities through mutualistic interactions. For example, a native species may provide refuge or effective protection against predators. The invasive species would benefit from this anti-predator association, whether or not this was also beneficial for the native species. Such interactions are called symbiosis or commensalism respectively.

From South America, the monk parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus) has become one of the most successful invasive birds with populations established in cities on all continents. Due to the international wildlife trade, monk parakeet was a common pet during the last decades that, consequently, has given rise to invasive populations. The monk parakeet is the only parrot species that builds its own nest, composed of wood sticks and located on trees and human facilities.

The largest population of monk parakeet in Spain is in Madrid, where we observed an unusual nesting behaviour, given that some monk parakeets were associated with large nests of a native species, white stork (Ciconia ciconia), while invading the surrounding rural area. But if monk parakeets are able to build their own nests, why were they associated with white stork nests?

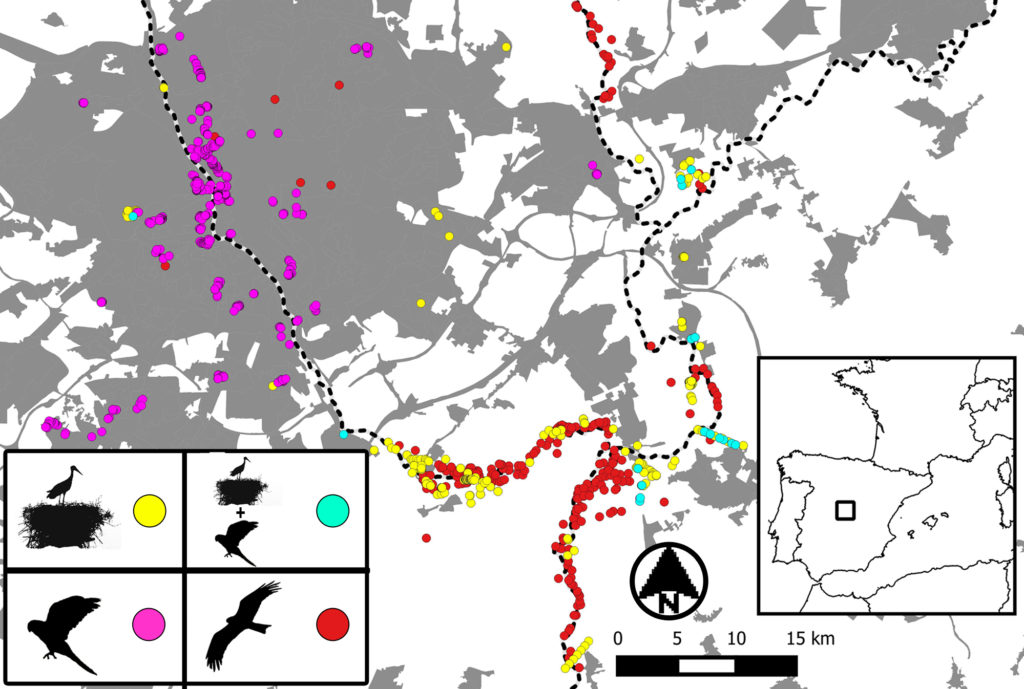

In light of this, we assessed the probability that both species were associated to reduce the predation pressure from the raptor community, because white storks lack predators and would indirectly protect the monk parakeets in their nests. During two breeding seasons, we located all nests of parakeets, storks and raptors in an extensive area that covered urban and rural habitats. We also recorded interactions between monk parakeets and raptors in the proximity of parakeet nests to assess their responses facing predators.

As we hypothesised, monk parakeets developed a commensalism relationship with white storks against the predation pressure from raptors. This relationship was more likely in rural areas where the raptor pressure was higher than in urban areas. Monk parakeets additionally preferred nest locations with low presence of raptors and high presence of other conspecifics.

According to this specific spatial distribution of their nests, monk parakeets showed a strong dependence for the anti-predator defence provided by white storks because parakeets abandoned their nests after the abandonment of the nest by the white stork. Likewise, monk parakeet mostly did not flush when a raptor came close to its nest if it was associated with a white stork, unlike parakeets without associated storks.

Overall, our results shed lights on the complexity of biotic interactions in biological invasions and how contrary effects between commensalism and predation pressure may influence biological invasion success. We provide more information about mutualistic associations in biological invasions, an ecological interaction rarely studied between vertebrates.

In conclusion, unexpected interactions may arise between invasive species and recipient native communities, then we hope that our work assists to the development of effective management plans facing the global problem of biological invasions, such as enhancing the predator community as an effective biological controller.

Comments