Animal colors and patterns can play many roles, from social signaling, to reducing detection by potential predators, to protection against some other environmental pressure. Different color morphs can arise within populations of the same species exposed to different levels of predation or environmental stress and in some cases can arise within an individual’s lifetime as a result of phenotypic plasticity.

One such species, in which two distinct color forms exist, is the Kerry spotted slug Geomalacus maculosus, a terrestrial gastropod of conservation interest. This species is found only in the West of Ireland and North-Western Iberia and is protected under the EU Habitats Directive on the basis of this restricted distribution pattern.

One of the current research efforts of the Applied Ecology Unit, NUI Galway, is to understand the behavior and ecological requirements of G. maculosus in Ireland in order to help inform conservation strategies for this species.

The camouflaged slug

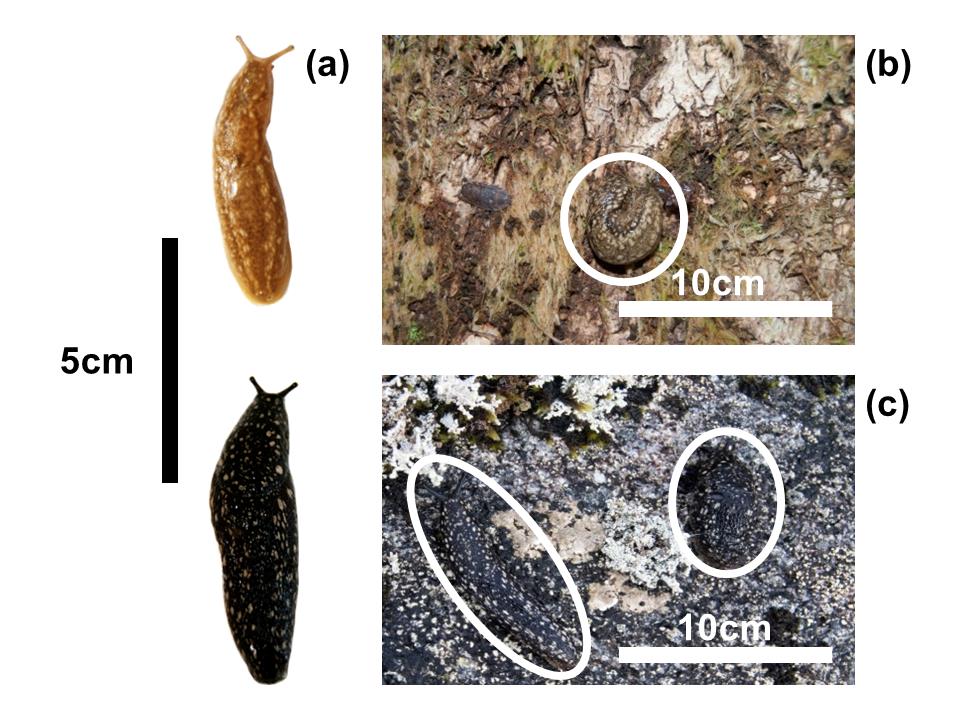

Aside from its status as a protected species and its extremely limited global distribution, one of the most striking traits of this slug species is its spotted patterning, with two seemingly distinct color morphs occurring in different habitat types. Within forested habitats, G. maculosus occurs as a hazel-brown to ginger-brown slug with yellow-gold spots, whereas in open areas such as blanket bogs, the slug occurs as a dark grey to jet black animal with white spots (Fig. 1a).

Each distinct color morph appears to provide accurate camouflage against the different substrates found in each habitat, with brown slugs resembling the appearance of moss and lichen-covered tree bark (Fig. 1b) and black slugs resembling a lichen-covered boulder outcrop (Fig. 1c).

We assessed phenotype-environment matching in G. maculosus populations from a number of forested and blanket bog habitats across its Irish distribution using digital photography and color scoring to determine whether the color scores of slugs correlate with color scores of their background substrate, and whether phenotype-environment matching is habitat-specific.

We found that animal and substrate scores were strongly and positively correlated for brown slugs and forest substrate and for black slugs and blanket bog substrate. Conversely, there was a significant difference between the color scores measured from brown slugs and blanket bog substrate, and between black slugs and forest substrate. This suggests that each G. maculosus color morph provides camouflage against their background substrate which is habitat-specific.

A question of diet?

We initially thought that diet may play an important role in determining G. maculosus skin coloration

We repeatedly observed that recently-hatched juvenile G. maculosus from both forested and open habitats were brown. This motivated us to test whether the black phenotype, found in open habitats, is environmentally-induced.

Since slugs generally eat the substrate on which they are found, and since there is a published example of diet-induced pigment change in other arionid slug species, we initially thought that diet may play an important role in determining G. maculosus skin coloration.

We reared newly-hatched G. maculosus on different colored food types with the expectation that carrot-fed slugs would develop more reddish pigmentation, oat-fed slugs would become overall paler and spinach-fed juveniles would develop greenish pigmentation. We found that all juveniles became slightly darker over the course of 3-month feeding trials but this was irrespective of diet.

The light bulb moment

Blanket bog habits are open and exposed compared to the relative shade of forests. We therefore hypothesized that lighting, in particular exposure to UV radiation, may influence the development of black pigmentation in G. maculosus living in open habitats.

We reared newly-hatched slugs under two different lighting conditions – a container fitted with a UV bulb and a container kept in constant darkness – and measured the relative color scores of these slugs each month. Slugs reared under UV lighting became increasingly darker, and developed black pigmentation typical of G. maculosus found in open habitats (Fig. 2).

Slugs reared under UV lighting became increasingly darker, and developed black pigmentation typical of G. maculosus found in open habitats

We examined skin sections of slugs reared under both conditions and found that the UV-exposed juveniles had significantly more black pigment in their epithelium than darkness-reared juveniles. Considering this pigment would have developed in response to UV cues, we concluded that it is most likely melanin.

What does this mean for conservation and protection of the species?

Skin coloration in G. maculosus appears to play a dual role in both photoprotection and in making slugs less conspicuous to predators in both open and forested habitats.

The ability of G. maculosus to alter its skin pigmentation may also have consequences for the conservation of this species. Commercial conifer forests have recently been recognized as important habitats for G. maculosus in Ireland. When forests are clear-felled to harvest timber, slugs remaining in clear-felled areas develop the black ‘bog’ phenotype but, since they are most active on felled tree stumps, the effectiveness of their camouflage is likely to be lower than that of the brown ‘forest’ phenotype.

Past research has shown that forest clear-felling reduces G. maculosus population sizes. Therefore research regarding predation rates on the slugs of each phenotype in both clear-felled and unfelled forest stands would contribute to the development of mitigation measures to reduce the effects of clear-felling on G. maculosus populations.

Aidan O’Hanlon

Latest posts by Aidan O’Hanlon (see all)

- The curious case of the color-changing slug - 18th August 2017

Comments