At least 50 million years ago, long before human ancestors resembled apes, bats were already using echolocation to hunt for insects. Currently more than 1,300 bat species occupy a wide variety of ecological niches —from highly specialized echolocators to the fascinating vampire bats—living in every continent around the world, with the exception of Antarctica. Their exceptional biology has been the source of inspiration for researchers of many scientific disciplines, spanning from ecology to engineering.

Currently more than 1,300 bat species occupy a wide variety of ecological niches.

This month, an ambitious new consortium known as ‘BAT1K’ is being launched at the Berlin Bat meeting. BAT1K is an international effort being led by Emma Teeling (IRE), Sonja Vernes (NL), David Ray (USA), Liliana Davalos (USA) and Thomas Gilbert (DEN) that aims to sequence the genomes of all bat species currently living on earth using cutting edge methods to produce high-quality, chromosome-level assemblies. Unravelling the genetic secrets of bats will help us understand their unique features, their unparalleled diversity and aid in conserving numerous bats species that are currently endangered.

What makes bats special – longevity

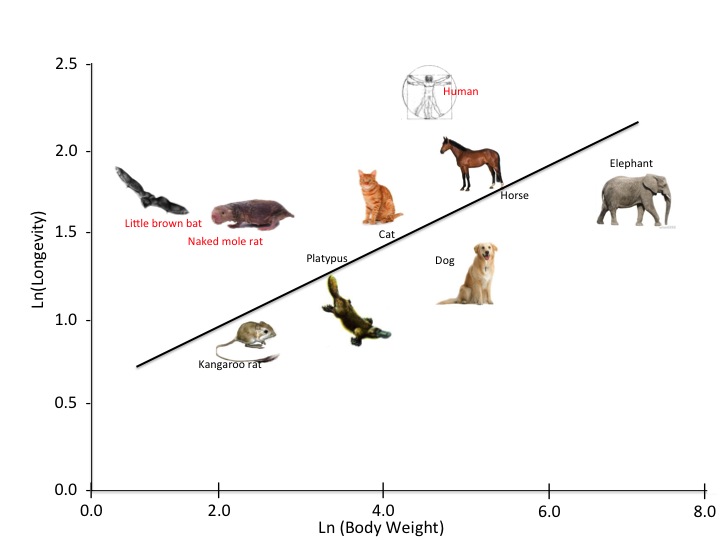

An animals’ life span is typically directly proportional to their size. Bats, however, are an exception to this rule. Brandt’s Bat (Myotis brandtii) are the longest living bats, living up to ~40 years of age. Mammals that have a similar weight, like mice, typically only live for 2 -3 years. Why? A bat’s ability to fly may have extended their lifespans.

Flying requires intense physical exertion, which results in the production of “free radicals” that can lead to tissue damage. Researchers have demonstrated that bats evolved genes that rapidly and efficiently repair this damage, which might in turn contribute to their longevity. Sequencing diverse bat genomes can provide us clues on how bats combat ageing and how we might limit the progressive decline of cells and tissues that we see in humans during ageing or in pathologies such as cancer.

What makes bats special – immunity

In addition to living a long life, bats may be tolerant to many viruses. In humans, contact with viruses like Ebola, SARS or Hendra usually results in severe illness or even death. By contrast, bats are much more robust, rarely showing physical symptoms in response to such infections. It has been hypothesized that the bat’s immune systems are perpetually heightened to keep such infections at bay.

In addition to living a long life, bats may be tolerant to many viruses.

A better understanding of how bat genomes have evolved to encode this naturally heightened defense system will have wide ranging implications for understanding how to protect humans against these external viral threats.

What makes bats special – senses

Bats are famous for being able to ‘see’ using sound (echolocation), but not all bats see the world the same way. Whilst most bat species use echolocation to navigate and hunt for insects (e.g. Myotis davidii), some use sight and smell to forage for fruit (eg. Pteropus alecto). These two species, like all bats, share a common ancestor, and yet, over evolution their different environments lead to diversification and reliance on different senses.

Comprehensive genome sequencing across bat species, will make it possible to track how bat genes have evolved to favor the auditory or visual system and as well as the evolution of sensory encoding in mammals.

What makes bats special – communication

Bats are one of the few mammals that can learn how to produce new vocalizations.

Bats are extremely social animals, often co-habiting with hundreds or thousands of other bats. Hence social communication is key for maintaining interactions with one another. Bats can use social calls for multiple purposes; such as identifying individuals in a group, negotiating sleeping arrangements, hunting for food together or attracting a partner.

Bats are one of the few mammals (apart from humans, elephants, seals and whales) that can learn how to produce new vocalizations. So in essence, just as children learn how to speak from their parents, bats learn how to make new calls. The genetic sequencing of bats will reveal the genetic parallels among bats, humans and other vocal learning mammals.

What makes bats special – ecosystems and conservation

Today there are more than 1300 different species of bats, 169 of them are considered vulnerable and another 77 are endangered. Bats are crucial for the pollination of many plants (e.g., mangos and bananas), and act as natural pesticides by eating thousands of insects each night. Declining bat populations present a massive threat to the environment.

Comprehensive genome sequencing of threatened species can help scientists track at risk populations and measure the effects of habitat change. Furthermore, it can bring species back from the brink of extinction by carefully designing breeding schemes to increase genetic diversity in remaining populations.

The BAT1K consortium will contribute to a range of research efforts, from the evolution of traits like flight, immunity and sensory modalities to bat conservation and even human disorder states and novel therapeutics. To hear more about the BAT1K consortium, follow us on Twitter, @bat1kgenomes or check our website – where you can also sign up to be part of BAT1K!

Sonja Vernes

Latest posts by Sonja Vernes (see all)

- The bat blueprint - 8th March 2017

Very interesting information about the bat and its special factors!