The number one cause of chronic kidney disease and end-stage kidney disease is diabetes, and the gold standard for diagnosing any kidney disease is through biopsy. Unfortunately, kidney biopsies are not without risks, and although minimal, there is a risk of bleeding and damaging the kidney further by performing this invasive procedure. In addition, some patients cannot have a kidney biopsy when they truly need one because of other comorbidities, anti-coagulant medications, and other factors that make them high risk for complications. Usually for patients with diabetes that present no other concerning findings, the nephrologist might assume its diabetic nephropathy, a complication of diabetes, without performing a kidney biopsy. Could they be making a mistake? It might be something else that is treatable. Is there another test we could do? What if there was an alternative for diagnosing diabetic nephropathy that is noninvasive and low risk?

Is there another test we could do? What if there was an alternative for diagnosing diabetic nephropathy that is noninvasive and low risk?

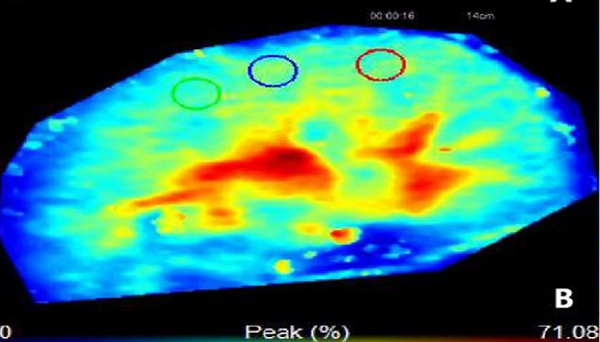

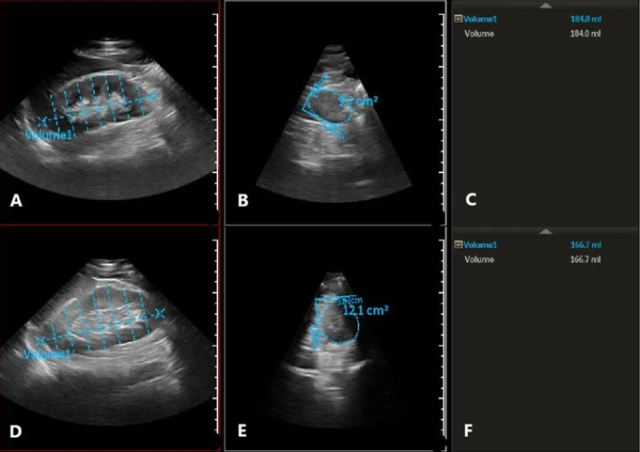

In a BMC Neprhology publication, Li et al., examine the potential use of specialized ultrasound – three-dimensional ultrasound and contrast-enhanced ultrasound – to diagnose diabetic nephropathy. This technology takes a large series of 2-D ultrasound images in rapid succession which are then assembled by a computer to create a 3-dimensional image. For pregnant women, a 3-D ultrasound may have been offered to you to look at your growing baby. Contrast enhanced ultrasound uses intravenous contrast agents consisting of microbubbles/nanobubbles of gas, which oscillate creating an “echo” when exposed to ultrasound waves. This is a better alternative when a patient cannot get contrast agents for a CT or MRI.

Li and colleagues used these two technologies to examine 115 patients with diabetes and kidney disease that underwent kidney biopsy to see if they could differentiate between diabetic nephropathy from non-diabetic renal disease (i.e., IgA nephropathy, membranous nephropathy). Sixty-four had diabetic nephropathy and 51 had non-diabetic renal disease. We know that diabetic nephropathy is more likely with longer history of diabetes and with other microvascular complications (like retinopathy). Li et al.’s data was consistent with these previous studies. They didn’t find any differences with contrast-enhanced ultrasound. However, they did find that using a logistic regression model for BMI and right kidney volume was statistically significant. They concluded that 3-D ultrasound has the potential to be an option in our arsenal for diagnosing diabetic nephropathy.

Li et al. is one of a many researchers looking at utilizing 3-D ultrasound for diagnosing and managing kidney pathology. Not surprisingly it’s been looked at for determining kidney volume in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. And Calio et al. examined 3-D contrast-enhanced ultrasound use in surveillance for renal cell carcinoma recurrence after ablation.

In my clinical practice, I’m not running out to get a 3-D ultrasounds just yet, but I’m keeping it in mind for the future. After further studies, I might be ordering it for that diabetic patient with chronic kidney disease to make sure I’m not missing something.

Comments