The return of tourism and its environmental consequences

As Covid-19-related travel restrictions are falling, tourism is returning with full force.

For the first quarter of 2022, international tourism saw a year-on-year increase of arrivals of almost 200%. The European market is leading this rebound with close to four times the number of international arrivals compared to the previous year.

While global tourism is still below its pre-pandemic size, this quick growth has surprised industry experts and increased recovery expectations. As of June 2022, roughly one in two experts anticipates a return to pre-pandemic levels by 2023.

This isn’t just good news for Airbnb landlords and travel bloggers – tourism is also a main driver of economic growth, particularly in less developed economies. The importance of tourism has been recognized in the UN Sustainable Development Goals, where the sector finds direct mention in three of the seventeen goals.

In many cases, however, this economic progress comes at the cost of serious environmental consequences.

Before the pandemic, tourism and related activities accounted for an estimated 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions. And even as the sector itself will be heavily affected by the change in global climate, these emissions are expected to grow in the coming decade.

It is this trade-off between economic benefits and environmental costs that well thought-out policies and guidelines will need to balance. Developing nations in particular should aim to harness the economic potential of tourism while mitigating adverse environmental effects.

Such policies require accurate and timely data to inform policy design, and to assess the effects of the implemented measures.

How unconventional data sources can inform development statistics

Procuring this accurate and timely data poses a challenge for policy makers across all areas – and tourism is no exception.

Take the European Tourism Indicators System (ETIS), a management and monitoring tool created by the European Commission to allow destinations to measure their sustainability performance. Some of the data used in the system is readily available from national statistics offices, other data is collected through surveys.

The European Commission suggests relying on three-year cycles for the collection of some indicators because of the time and cost intensity of these surveys. The need for cost savings thus decreases the temporal accuracy and availability of the sustainability indicators.

And even under these guidelines, researchers have found more than half of the indicator data to be missing after the first implementation of the system in some regions.

Tapping into alternative forms of data might help to improve indicator frameworks. In other areas of economic and social development statistics, their potential to collect information has been explored with promising results.

Examples include data from social networks and trading platforms as well as mobile phone records and satellite images.

The findings in these studies are especially relevant as the estimated models can be used at high frequency and geographical accuracy while having low total cost.

Granted, these unconventional data sources will not replace the gold standard of large-scale, statistician-led surveys for a long time, maybe never. But they are able to offer additional information, increase coverage and fill gaps with good estimates.

Looking towards platform data for tourism statistics

So how do these ideas apply to the measurement of sustainable tourism?

In our recently published work, we approach this question and find tourism platform data to be a valuable source of information for understanding the degree of sustainable tourism in different countries.

In the study, we focus on tourism in Europe, the world’s largest market. Using a web-scraped data set of over 65,000 listings from TripAdvisor.com and applying a range of statistical learning techniques, we find accommodations’ representation on the travel platform to be a good predictor of their sustainability practices.

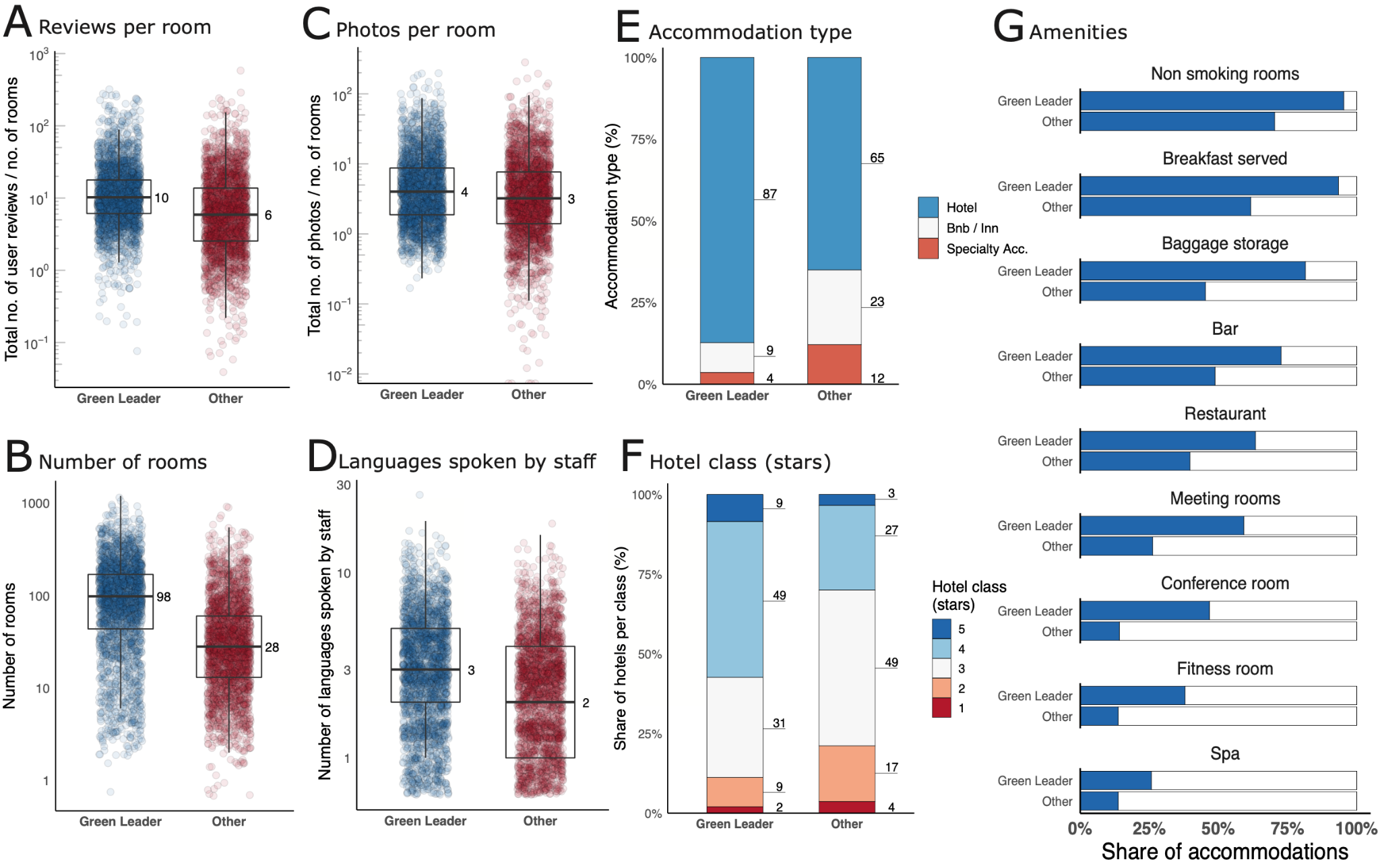

For example, the data shows that accommodations that were awarded a sustainability badge on the platform show higher rates of user engagement, and quality features (see Fig. 1).

Based on these features, we trained a range of machine learning models, which can successfully predict the sustainability level of touristic accommodations.

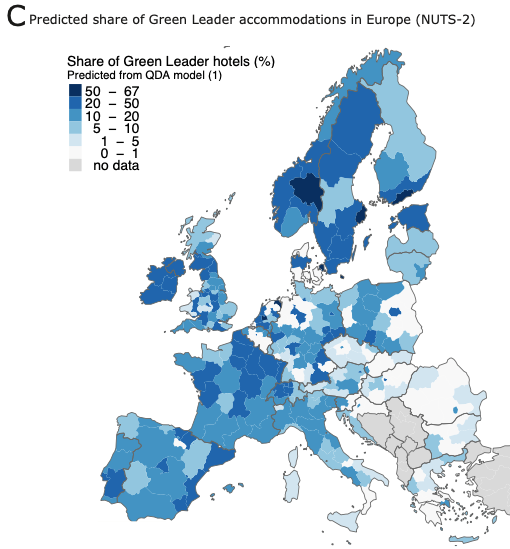

Due to the highly available nature of the data source and models, we are then able to predict the proportion of sustainable accommodations for additional countries at no additional cost (see Fig. 2).

In other words, the online platform data in combination with the machine learning models allow us to estimate the proportion of sustainable tourist accommodations across all countries with TripAdvisor presence across the globe.

The Takeaway

Whether 2023 or later, tourism will fully return to pre-pandemic levels, and with it the emissions it causes.

Unconventional sources of information such as data from the online platform TripAdvisor and machine learning approaches can help to fill data gaps to track and manage sustainable tourism across the globe.

Such information can aid the design of better policies to keep tourism within the planetary boundaries.

The results of the study as well as the data and code to reproduce these results are freely available here.

Comments