The Impact of Dementia

Dementia is the name of a group of progressive diseases that affect cognition and other crucial functions of the brain. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia, followed by vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies and frontotemporal dementia. Age is the main risk factor; there is a 1 in 15 chance of developing dementia at the age of 65, increasing to 1 in 3 for those over 85.

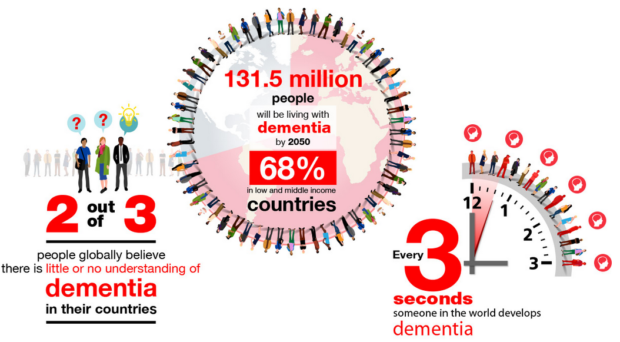

As our world population rapidly ages, there are a growing number of people who develop dementia. Research showed that in 2015, there was one new case of dementia somewhere in the world every three seconds. This is four times as much as new cases of HIV/AIDS. There is currently no cure for dementia.

The impact of the disease is huge: for the individual, who lose the grip on their life; for the family who care for a person with dementia; and finally for society, that has to deal with the growing group of people in need of care and support. In the highest income countries, the cost of dementia care is already more than that for cancer and heart disease combined.

Almost 50 million people worldwide have dementia, and almost 60% live in lower and middle-income countries (LMICs). This number is expected to increase to over 130 million by 2050. I know from my own family experience how difficult it is to deal with dementia and I see in both countries where I spend most of my time, the UK and Netherlands, how they struggle with finding the resources (money and qualified people) to provide care and support to people with dementia.

The response to dementia

Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI) is the global federation of 85 Alzheimer associations throughout the world, in official relations with the World Health Organisation (WHO) and United Nations (UN). Our mission is to strengthen and support Alzheimer associations, to raise awareness about dementia worldwide, to make dementia a global health priority, to empower people with dementia and their care partners, and to increase investment in dementia research, especially in LMICs.

ADI supports the creation of high-level governmental plans to deal with the growing impact of dementia. These plans are capable of addressing problems unique to each country, promoting the creation of infrastructure necessary to build dementia-capable programmes. This approach has worked very well in other disease areas like cancer and HIV/AIDS.

Despite dementia now being recognised as one of the major health and social problems of the 21st century, only 28 out of the 193 WHO member states have developed national plans and policies with half of them being in Europe. This is why we support the decision of the World Health Organization to develop a global plan of action. The WHO connects all the Ministries of Health around the world and the draft for this plan means that all of them must consider their role and position in dementia policies for the future.

The Zero draft for the Global Action Plan covers seven policy areas: (1) a public health approach, including developing national plans and involving all of governments, (2) the importance of raising awareness and making societies more dementia friendly and inclusive, (3) prevention and risk reduction for dementia, (4) improving diagnosis, care and treatment, (5) support for caregivers, (6) data collection on dementia in each country, and (7) stimulation of more research and innovation.

I welcome this comprehensive approach and the additional inclusion of palliative care and respite care under area 4. It offers a roadmap for national action and developing policies, goals, targets and indicators for national and even regional or state plans in the bigger countries.

Where do we begin?

I often get asked where to start. The number one need is improving understanding and acceptance of dementia – treating people as human beings that should not be excluded from the community or from contact with their friends and families. Awareness can be raised in many ways, including by supporting World Alzheimer’s Month every September.

The second most important thing is diagnosis, treatment and care. Diagnosis can empower people with dementia and their families to face their situation, seek help and plan for the future. In parts of the world, health care professionals hesitate to make or disclose a diagnosis, because ‘nothing can be done’. This is not true! Lots can be done.

There are many psychological and social programmes that have proven to be effective in supporting people with dementia and their families, like physical activity, cognitive stimulation, musical therapy, arts and dementia projects, support programmes for caregivers and Alzheimer or memory café activities.

We can also make our societies more dementia friendly, by training frontline staff of local services like supermarkets, police or banking how to respond to people with dementia in their day-to-day life. There are now many positive examples of such projects from around the world.

Dementia is a global problem and that is why we need a global response. But the individual response is also important, in your own family or local community. It is not complicated but requires a little understanding and an attitude of including people with dementia, engaging with them and listening to their stories and needs. It can be done. I hope the WHO plan will contribute to this response all over the world.

Comments