Dr Marco Medici is a MD and PhD at the Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. His research is focussed on the genetic basis, consequences and treatment of thyroid diseases, including thyroid nodules and cancer. He is the PI of an international consortium investigating the genetic basis of thyroid dysfunction, including over 60,000 participants. He recently finished a postdoctoral research fellowship at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, USA. Dr Medici has published more than 30 peer-reviewed publications in multiple journals, including Endocrine Reviews, PloS Genetics, Clinical Chemistry and the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

Dr. Erik K Alexander is the Chief of the Thyroid Section at the Brigham & Women’s Hospital, and an Associate Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Alexander is a clinician and clinical researcher, with a primary focused on thyroid illness as well as the care and management of patients with thyroid nodules and cancer. He is a member of the American Thyroid Association’s 2015 clinical guidelines for the management of patients with thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer, and is co-chairing the ATA 2016 guidelines on thyroid illness during pregnancy. He is current a member of the ATA’s Board of Directors. Dr. Alexander has published over 100 peer-reviewed articles in multiple journals including the New England Journal of Medicine, JAMA, and the Annals of Internal Medicine. He has an active clinical practice, and is a resident of Boston.

How are thyroid nodules currently managed in clinical practice?

Most thyroid nodules are either detected by the patient, the physician, or as a chance finding on cross-sectional imaging. Once detected, ultrasound is recommended, often followed by fine needle aspiration when the nodule is larger than 1-1.5cm or has high-risk sonographic characteristics. In most cases, cytology is benign, usually leading to a recommendation for conservative (i.e., non–surgical) management. A cytological result which is positive or highly suspicious for malignancy leads to thyroidectomy.”

However, some cytological results cannot discriminate between benign and malignant disease and are often termed cytologically indeterminate. Diagnostic molecular panels assessing DNA mutations/translocations have demonstrated an ability to improve preoperative risk assessment of thyroid cancer in these cytologically indeterminate nodules. However, our full understanding of the meaning of these mutations remains uncertain.

What are RAS-oncogene mutations?

The RAS gene encodes a family of three isoforms, NRAS, HRAS, and KRAS, with numerous different mutations described. These mutations stimulate various cellular pathways, including the MAPK and PI3/AKT signaling pathways, which have all been linked to thyroid tumorigenesis.

What led you to investigate RAS mutations in a general population of thyroid nodules?

Mutations identified in most thyroid carcinomas are known to activate pathways regulating cellular growth, development, and/or malignant transformation, which has led to the assumption that thyroid nodules harboring such mutations are either cancerous, or at high risk for eventual malignant transformation.

However, observational data question this assumption as absolute and suggest that all such pathways or activating mutations may not prove equally oncogenic. In particular, clinical outcomes of patients with mutations in the RAS gene are highly variable, and most studies investigating RAS mutations have been restricted to nodules with indeterminate or malignant cytologies. To obtain a more complete understanding of the variable phenotype of RAS-oncogene mutations, we therefore determined RAS mutational status in an unselected nodule population whether cytologically benign, indeterminate or malignant.

How do your findings build on and differ from the results of previous research?

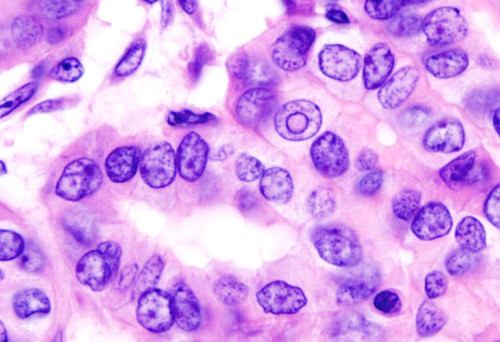

As our analysis was not restricted to nodules with malignant or indeterminate cytology, we were able to investigate the impact of RAS mutational status across the full spectrum of nodular disease. Half of all RAS-positive nodules prove malignant. However, all of these malignancies were low risk – all follicular variants of papillary carcinoma, without extrathyroidal extension, metastases, or lymphovascular invasion. The other half of the RAS-positive nodules were benign and behaved in an indolent fashion over many years.

You mention RAS-positive nodules behave in an indolent fashion over years. What does this mean for the patient?

In our sample, the RAS positive benign nodules remained stable in size over many years of ultrasound evaluation, and did not show any signs of malignant transformation on repeat aspiration during follow-up. This suggests that RAS-positive cytologically benign thyroid nodules can be considered low risk nodules. Importantly, these data also refute a clinical assumption that all RAS mutations lead to oncogenic transformation in affected thyroid nodules. Further investigation is required to better understand this process.

How could your results influence clinical decisions?

Our data demonstrate a more indolent and variable phenotype of RAS-positive nodules than previously described. RAS-positive thyroid nodules, especially in older individuals, frequently demonstrate a benign phenotype. This study therefore supports the utility of fine needle aspiration cytology in guiding the clinical management of RAS-positive nodules. Cytologically benign nodules, even if RAS-positive, may be candidates for a non-operative observational strategy of repeated sonographic evaluation or fine needle aspiration. Even if malignant, most RAS-positive thyroid nodules appear to be low-risk histologically, and thus are likely to be highly treatable.

BMC Medicine: passionate about quality, transparency and clinical impact

2014 median turnover times: initial decision three days; decision after peer review 41 days

Comments