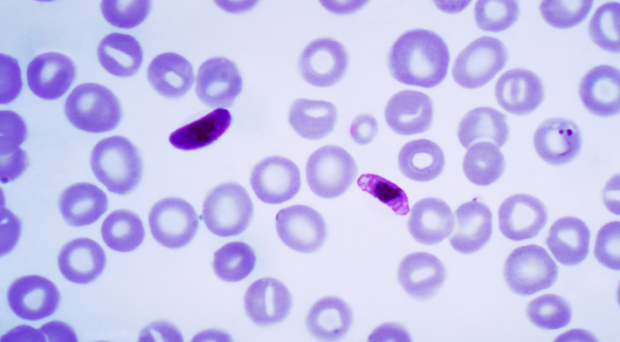

Platelets are cells that circulate in the blood and play an integral role in the prevention of bleeding. A reduction in their number, a state termed thrombocytopenia, has long been recognized as a typical laboratory finding in patients with malaria.

Previously, this has attracted limited clinical interest as significant bleeding is not common in these patients and their platelet count rises rapidly and spontaneously as the malaria is treated. However, recently some authors have suggested that the presence of severe thrombocytopenia on initial assessment indicates which patients are at greatest risk of death and have proposed that it should be included in the WHO definition of severe malaria.

The WHO definition of severe malaria is a collection of clinical and laboratory criteria, developed through expert consensus, that aims to help clinicians identify the patients most in need of hospitalization.

Because patients with malaria can present with an array of clinical signs and symptoms and a variety of laboratory abnormalities, this definition contains many different criteria.. However, critics have suggested that the sheer number of criteria makes the definition cumbersome and its everyday use in clinical practice challenging.

Studying thrombocytopenia as an indicator of severe malaria

Our study in BMC Medicine enrolled only patients with the most severe malaria and on admission to hospital the platelet count was, on average, lower in the patients that would later die.

However, the platelet count did not independently predict patient death when considered with several other well-validated measures of disease severity. Importantly, knowledge of the platelet count did not improve the identification of high risk patients beyond determining their RCAM score, a simple clinical predictive score that can be calculated in less than a minute at the bedside.

While the platelet count was generally lower in the patients that had major bleeding compared to those that did not, it failed to identify either population reliably.

Although a very low platelet count should alert the clinician to the presence of severe malaria, these patients will usually have already been identified with simple clinical assessment and traditional laboratory measures of disease severity.

The addition of yet another criterion to the already complex definition of severe malaria has the potential to make the definition even more unwieldy, without substantially changing the fundamental management of patients with the disease.

When patients with platelet count less than 50000 who are smear positive for Malaria are tested for Dengue IgM, it has turned out to be positive in at least two of my patients implying coexistent Malaria and Dengue in the same patient.