A mother cradles her child. Her son has developed a fever. His blanket is damp from heavy sweating. He lets out a piercing scream, the headaches have started again. She strokes his forehead and rocks him gently. “He’s been sick?” the doctor asks. The mother nods. All the symptoms point to malaria. A simple test could confirm the doctor’s prognosis. However, the clinic’s resources are limited, no microscope and no diagnostic tests. He has to act on observations alone and writes out a prescription for anti-malarial drugs.

Although hypothetical, this is a common scenario in Sub-Saharan Africa, where poor resources and inadequate laboratories are detrimental to public health. There are two commonly used methods for malaria diagnosis: laboratory diagnostic methods and symptomatic diagnosis. In the laboratory diagnostic method, blood samples are analyzed for Plasmodium parasites (the causative agents of malaria in humans) using a microscope. For the symptomatic method of diagnosis, patients are self-diagnosed based on symptoms and given a prescription to treat the perceived malaria.

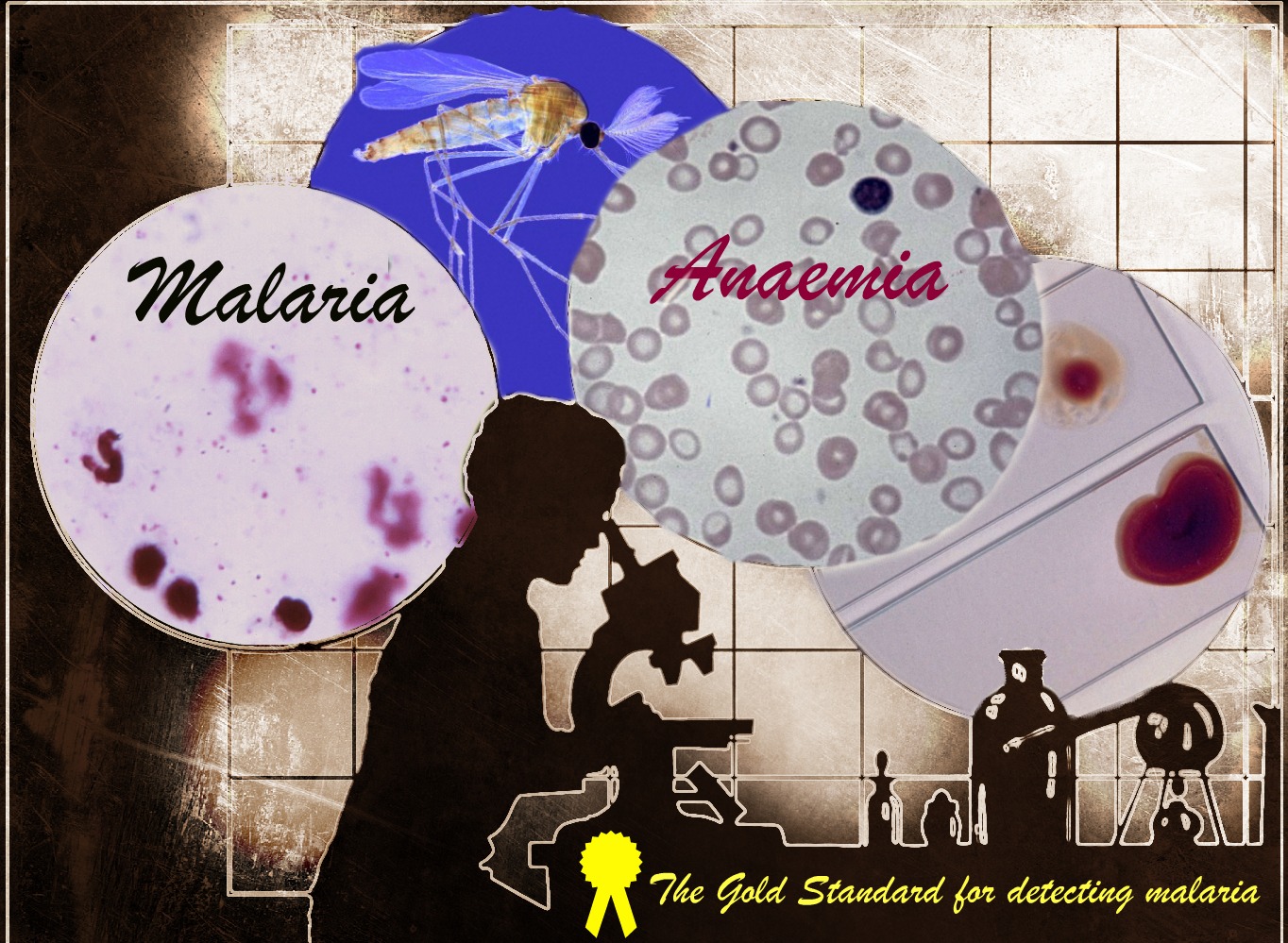

Blood sample analysis is the gold standard diagnostic method for detecting malaria. However, such laboratory diagnosis is a luxury in malaria endemic regions; one that is sadly out of reach for many patients. The majority of feverish patients must rely on the imprecise means of self-diagnosis.

In light of World Malaria Day, the difficulty of diagnosis is high on the agenda. Dr Joseph Choge and his fellow colleagues are just one team amongst an army of researchers who are desperate to prevent the continued indiscriminate use of anti-malarial drugs as it will inevitably lead to drug resistance. In a fight against the resilient Plasmodium parasite we cannot afford to aid its conquest.

In Western Kenya, Dr Choge’s recent study found that anemia is slipping under the radar, masked by a malaria fear haze. He and his team compared the discrepancy in malaria and anemia burdens between self-diagnosed patients with those diagnosed by blood sample analysis. Most patients’ laboratory results contradicted self-diagnosis. Instead of malaria, the blood samples proved positive for anemia. Dr Choge confirmed that malaria is over-diagnosed considerably, whilst other diseases, such as anemia, are overlooked and not treated in a timely manner.

Although fever, high temperature, sweating, shivering, vomiting and severe headaches are common symptoms indicating the presence of a number of diseases, malaria is the prime suspect. Naturally, civilians are highly suspicious of it. The problem, as explained by Dr Choge, is when suspicion acts as the sole basis for treatment and anyone suffering from fever-like symptoms is presumed to have malaria.

Unfortunately, it will not be an easy or simple task to improve the diagnostics and management of malaria. Laboratory diagnosis requires a microscope to analyze blood samples, but there are a limited number of hospitals that can perform proper laboratory diagnosis and functional microscopes are not available in most health facilities.

The good news is that there are alternatives. Malaria rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) can complement microscopy, albeit at lower quality. Another drawback of RDTs is their practicality for local staff in remote areas and higher market price of U.S. $0.55-U.S. $1.50 compared with microscopy at U.S. $0.12-U.S. $0.40 per malaria smear.

Despite the challenges up ahead, self-diagnosis is unsustainable and can no longer serve as the basis of therapeutic care. This has driven the development of innovative tests to develop more accurate, more sensitive and more specific malaria diagnostics. Professor Sanjeev Krishna, Section Editor for BMC Infectious Diseases, is pursuing new avenues for precision medicine with the hope to create “A revolutionary technologically where it never existed before”. Until better and more accurate point-of-care diagnostics can be developed a laboratory is necessary to confirm the presence of parasites for all suspected cases of malaria.

Comments