Today, 1st December, I’m sure many of us started by opening the first door of our advent calendars. The Christmas countdown beginning and all excited for mince pies and mulled wine. But 1st December, has great significance for millions, as it marks World AIDS Day, an opportunity for people worldwide to unite in the fight against HIV.

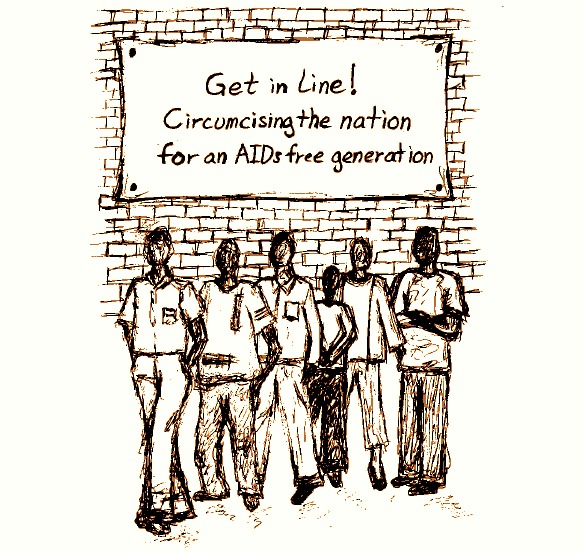

An estimated 34 million people have HIV worldwide. Due to the millions upon millions who have died from it, it has become one of the most destructive pandemics in history. Fortunately, the tide is turning in the AIDS pandemic. Rwanda is taking a rare and historic approach. In BMC Medicine the science community propose ‘circumcising a nation’, a bold strategy that focuses on the efficiency of task-shifting, judicious use of resources, and the leadership of civil society. Although the aims are admirable, is circumcising 700,000 men really achievable by the end of 2015?

The global scientific community believe they’ve found a way to achieve an AIDS-free generation. Their strategy is a multi-pronged approach that targets both prevention and treatment of HIV, revolving around the scale-up of voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) in sub-Saharan Africa.

Male circumcision involves the removal of all or part of the foreskin of the penis. Scientists and health practitioners recommend the procedure because the foreskin is susceptible to HIV and its removal could improve one’s overall wellbeing, not only limiting the risk of HIV, but reducing cancer risk and sexually transmitted diseases.

The inside of the foreskin is soft and moist, increasing the likelihood of a tiny tear or sore that allows HIV to enter the body more easily, and the foreskin itself contains many cells that are receptive to HIV acquisition. Research has found that after circumcision, the skin on the head of the penis becomes thicker and is less likely to tear. VMMC can reduce the lifetime risk of male acquisition of HIV by about 60%. Women too will benefit indirectly, as a reduced prevalence of HIV in males will reduce the risk of women that have sex with HIV-positive men.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) have been the two main drivers of this scheme, endorsing innovative approaches to increase VMMC uptake. They identified thirteen priority countries, where HIV incidence remains high, but the prevalence of male circumcision is low. These countries are all eastern and southern African nations: Botswana, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

The aim is to reach 80% coverage of VMMC in these 13 countries by 2015. Therefore, 20 million males need to be circumcised by the end of next year! Although challenging, reaching this target is estimated to avert 3.36 million new HIV infections in these priority countries. It will cost around US$1.5 billion, but could save US$16.5 billion, due to averted treatment and care costs. It has also been suggested that VMMC would reduce HIV incidence in Eastern and Southern Africa by roughly 30–50% over 10 years.

However, implementation in most of these target countries has been slow, with prevalence of VMMC lagging far behind the goal of 80% coverage. As of 2010, only 2.7% of the total number of VMMC procedures needed to reach this coverage level had been performed. The pace has now quickened, but of all priority countries, only Kenya appears to be on track, having achieved 50% VMMC in some regions and up to 80% in others. Meanwhile, its neighbour, Rwanda, has performed less than 10% of its target.

Lagging behind its neighbours, Rwanda, has stepped up and set an ambitious goal of performing 700,000 VMMC procedures by 2015. With support from the WHO, UNAIDS and the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, the Rwandan government is promoting VMMC as a back-bone strategy of a comprehensive national HIV strategic plan. However, Rwanda does not have a history of traditional circumcision and there are other challenges to contend with, such as a poor healthcare infrastructure and an over-burdened health system.

In Uganda, young men accepted the strategy and willingly got circumcised to reduce HIV infection despite having no prior tradition of circumcision. Men in Rwanda may accept it with the same ease. Rwanda will also need a meaningful communications strategy that explains the benefits of the procedure. They may follow Kenya’s example where a program of community mobilization, the use of mass media, and the inclusion of women were effective communications plan. The medical procedure of circumcision needs to be simplified as this will allow for VMMC to be task-shifted to lower-tier trained healthcare workers. Task-shifting of VMMC has been endorsed by the WHO as a component of scale-up strategies.

VMMC alone cannot and will not end the AIDS pandemic, but it is vital ammunition. Rwanda has to maximize the impact of the intervention and to accelerate the pace of service delivery.The question is, is this an overly optimistic target for Rwanda? We’ll just have to wait and see.

Comments