The synergistic confluence of artificial intelligence (AI, especially ‘deep learning‘, a type of machine learning) and the geographic/GIS (geographic information systems) dimension creates GeoAI. The latter is the term commonly used to refer to a battery of technologies that is much more powerful than the sum of its parent components (AI + GIS).

GeoAI opens up big opportunities and applications in health and healthcare, as location plays a key role in both population and individual health.

GeoAI opens up big opportunities and applications in health and healthcare, as location plays a key role in both population and individual health. Several disciplines within the domains of public health, precision medicine, and IoT (Internet of Things)-powered ‘smart healthy cities and regions‘ are benefiting from GeoAI, e.g., environmental health, epidemiology, genetics and epigenetics, social and behavioral sciences, and infectious diseases, to name but a few.

Geo-tagged big data collated from rich sources, such as social media streams, satellite imagery (remote sensing), IoT sensors in smart cities (e.g., monitoring air, light, and sound pollution), and personal sensing (via connected ambient and wearable sensors), can be reasoned with using GeoAI to answer many important research and practice questions in more comprehensive ways.

GeoAI technologies can capture and model our environment, linking the places where we live, work, travel, and spend our time to environmental, social, and other types of location-specific exposures, to explore their potential role(s) in influencing our health. They can also generate new hypotheses, predict disease occurrence, and help plan and monitor the deployment of effective health promotion and disease prevention and control programs within smart healthy cities. Besides these population-level GeoAI applications, there are further opportunities for integration of GeoAI and location-based information intelligence into precision medicine via well-tailored mHealth (mobile health) interventions targeting individual patients.

GeoAI applications and possibilities are not just the product of technological advances in recent years. GeoAI is ‘standing on the shoulders of giants,’ namely AI/deep learning and GIS technologies.

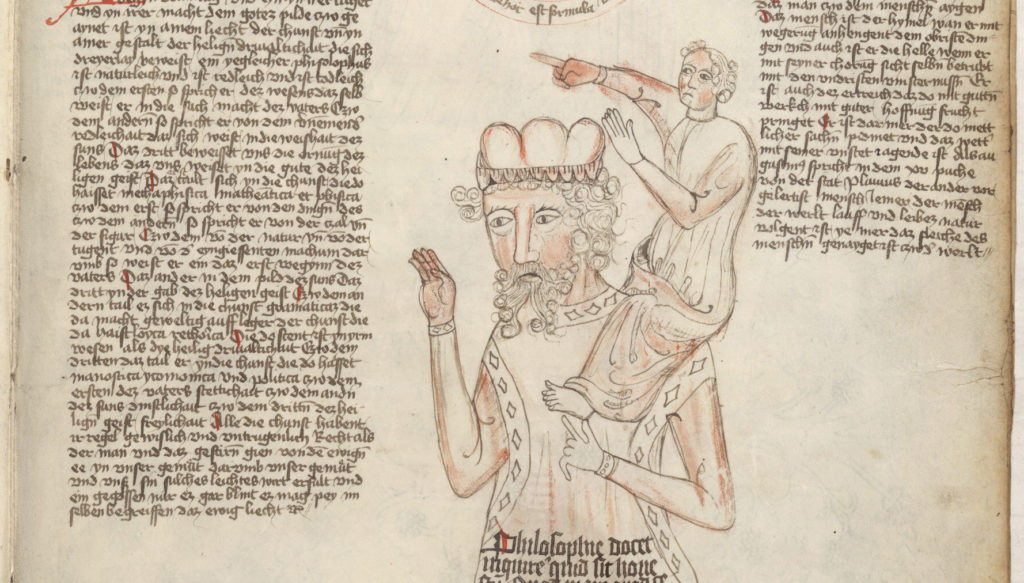

All of the above GeoAI applications and possibilities are not just the product of technological advances in recent years. GeoAI is ‘standing on the shoulders of giants‘ (Latin: nanos gigantum humeris insidentes), namely AI/deep learning and GIS technologies. These giants took many decades of hard labor of numerous (and often forgotten) scientists and scholars to develop and mature to their current forms.

For example, as many of us already know, deep learning is not a new term or an invention of the last several years. Deep learning was introduced to the machine learning community in 1986 by Rina Dechter, a computer scientist, and to artificial neural networks in 2000 by Igor N Aizenberg,also a computer scientist et al., decades before being brought to public attention in mainstream news media by Google after they bought the British start-up DeepMind in 2014. Aizenberg and colleagues were in turn building on the output of generations of scientists before them, including the first mathematical model of a neural network developed in 1943 by Walter H Pitts, Jr, a logician, and Warren S McCulloch, a neuroscientist.

Similarly, the field of GIS traces its roots back to the 1960s and even before that in the 1950s, thanks to the pioneering works of Waldo R Tobler, a geographer and cartographer, who in 1959 conceived MIMO (map in, map out), a model for computer cartography, and Roger F Tomlinson, OC, a geographer and the ‘father of GIS’.

Let’s always remember those before us who have laid the foundations for our present day and future innovations.

Comments