The human body is host to an incredible amount of bacteria – in fact, bacterial cells outnumber human cells within a person. A growing field of study is dedicated to examining this human microbiome along with its effects (both positive and negative) on human health, and uncovering which factors influence bacterial diversity.

It is well known that the human gut depends upon a microbial community, which, among other functions, helps digest food, combat harmful microorganisms, and train the immune system. However, it was unclear whether the human lung hosts its own unique microbial community. In fact, until recently the healthy human lung was considered sterile.

A number of studies based on airway samples had suggested the existence of viable human lung microbiota, but research was extremely limited. Moreover, it was unknown whether a microbial community in the lung could be associated with exposures or health outcomes.

What did we do?

Using a unique collection of fresh-frozen samples from normal lung tissue in cancer patients, researchers from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) were able to quantify and describe the microbial diversity in a collection of 165 individuals with lung cancer in a case-control study in Lombardy, Italy.

We showed that human lung hosted a unique microbial community associated with previous exposure.

Drs. Guoqin Yu, Mitchell H. Gail, Neil E. Caporaso and Maria Teresa Landi, of the NCI’s Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, sequenced a region of the 16S rRNA gene, found only in archaea and bacteria, from these patients’ non-malignant lung tissue samples.

Since the 16S rRNA gene varies across different types of bacteria, we were able to estimate the overall percentage of each type present in the samples. In addition, we described each microbial community by bacterial phylum and predicted function (i.e. what proportion is devoted to processing amino acids?)

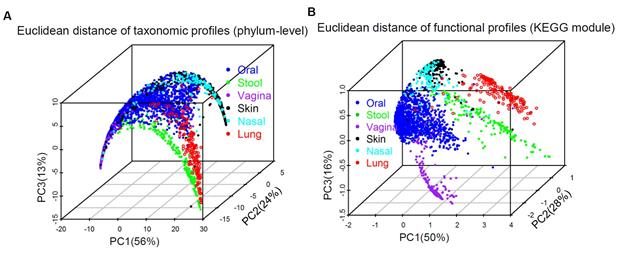

We compared our lung findings with data from the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) including data from other organs and processed it in the same way, using both phylum-level and microbial function profiles.

What did we find?

The dominant bacterial phylum in these samples was Proteobacteria (60%). Overall, the microbiota in the lung is clearly distinct from those found in the mouth, nose, feces, skin, and vagina (See Figure).

In our study, lung microbiota diversity decreased with history of chronic bronchitis and increased with environmental exposures, such as air particulates, residence in low to high population density areas, and pack-years of tobacco smoking. Certain bacteria were shown to be associated with patients’ cancer stage and metastases.

In addition, we showed significant difference in microbial diversity between nonmalignant tissue samples and tumor tissues taken from the same patient, with healthy tissue having higher diversity.

Ours is the largest lung tissue study to date, and shows that the human lung hosts a unique microbial community, which is associated with lifestyle and clinical outcomes. We will continue to examine the relationship of lung microbiota to human health.

Comments