Onchocerciasis, also known as river blindness, is a parasitic tropical disease that causes blindness and skin disease. It can be devastating. When I first visited an affected village in Burkina Faso, I was shocked to see blind people everywhere – a quarter of adults were blind. A feeling of despair permeated the village, it was terribly depressing.

Fortunately, onchocerciasis control has been very successful, first in West Africa (where there were 7 million people infected), then in the Americas (140,000 infected) and now we report an enormous decline in infection and massive progress towards onchocerciasis elimination in the remaining African countries (32 million infected before the start of control).

Vector control

When I joined the onchocerciasis control programme in West Africa (OCP) in 1983, vector control was used to interrupt onchocerciasis transmission. A fleet of helicopters sprayed every week biodegradable larvicides on riverine breeding sites of the blackfly vector that transmits the parasite.

This strategy worked, but it was not considered cost-effective or feasible for the rest of Africa. Hence, while the parasites were dying out in the OCP area, nothing was done for the affected populations of other African countries. As one of my OCP colleagues said: “they were left looking over the fence”.

Chemotherapy

Thankfully, in 1987, the drug ivermectin was shown to be safe and effective for mass treatment of onchocerciasis and donated free of charge for as long as needed by Merck & Co. That was a very exciting time: suddenly there was an intervention tool that could be used everywhere. It created a lot of momentum and led to the creation of the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control (APOC) to support all remaining endemic countries in Africa.

Intervention strategy

The question was then what strategy to use. Ivermectin kills the microfilaria, the parasite stage that is responsible for the disease manifestations, but it does not kill the adult worms. When these adults start producing large amounts of new microfilaria, treatment has to be given again.

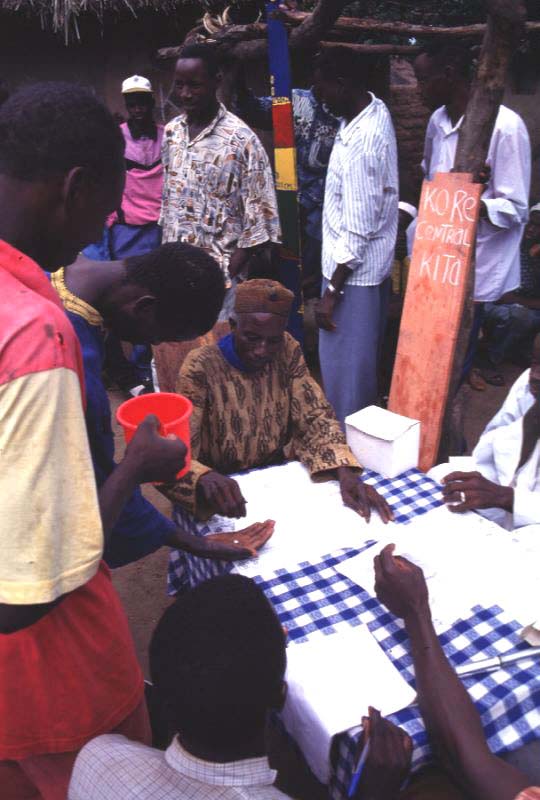

Subsequent randomized controlled trials showed that annual treatment was sufficient to prevent disease and APOC adopted therefore an annual mass treatment strategy to control onchocerciasis as a public health problem.

The microfilaria are also the source of transmission. Community trials in Africa showed that annual ivermectin treatment greatly reduced but did not interrupt transmission during the first years. Modelling predicted that in the long term elimination would be feasible but that it might take up 20 years.

A conference on the eradicability of onchocerciasis thought it very uncertain that ivermectin treatment could ever achieve sustained interruption of transmission in Africa where the vectors are highly efficient. In view of all this uncertainty, it was decided that APOC should initially focus on the control of the disease as a public health problem. The feasibility of elimination was then to be reviewed at a later stage when empirical evidence on the long-term impact of treatment would have become available.

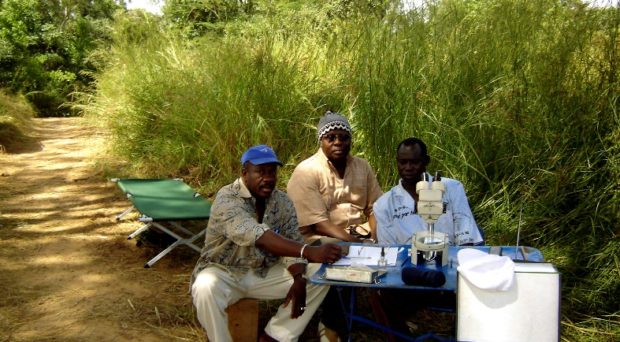

Operational research

In the early 1990s I moved to the WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) where I managed an operational research program in support of onchocerciasis control in Africa.

The initial focus was on the immediate needs of APOC: rapid epidemiological mapping, importance of skin disease, community directed treatment strategies etc. But later we started also looking into the elimination question through a longitudinal study in three foci in Mali and Senegal.

We showed that after 15 to 17 years of treatment onchocerciasis infection and transmission had fallen to very low levels. When treatment was then stopped, there was no renewed transmission and infection up to 5 years after the last treatment.

This provided the proof-or-principle that onchocerciasis elimination is feasible with ivermectin treatment, at least in some foci in Africa. The next question was to what extent this conclusion could be extrapolated to other settings with different vectors and endemicity levels.

Massive progress towards elimination

APOC was then mandated to “generate the evidence on where and when ivermectin treatment could be safely stopped”. Epidemiological evaluations were started to assess the decline in infection levels and progress towards elimination in the treatment areas, first in areas with the longest treatment history. The results for 58 areas with a population of 53 million people are reported in our article.

The results were beyond our expectations. Except for a few areas with insufficient treatment coverage, there was excellent progress towards elimination thresholds

The results were beyond our expectations. Except for a few areas with insufficient treatment coverage, there was excellent progress towards elimination thresholds and in many area the decline in prevalence was even faster than predicted. In 32 areas with a total population of 25 million people the prevalence of infection had already fallen to zero or was close to zero.

This is fantastic progress and at a massive scale: in savanna and forest areas, in areas with different vectors and endemicity levels, and in East, West and Central Africa. And using annual ivermectin treatment only.

The last mile

APOC was closed in December 2015, having achieved its original objective to control onchocerciasis as a public health problem throughout the APOC countries. Others will have to support the remaining activities for the last mile to elimination and to ensure that treatment is stopped where and when feasible. Not too early as this would lead to recrudescence but also not too late as that would be very costly.

As our results show, and as models predicted, the required duration of treatment is greatly dependent on the initial endemicity level.

As our results show, and as models predicted, the required duration of treatment is greatly dependent on the initial endemicity level. This needs to be taken into account in future decision-making as it would be most inefficient to apply a standard duration of treatment for all areas. Furthermore, given the active migratory behaviour of the vector, a regional rather than a country by country or project by project approach will be critical.

APOC has achieved more than it was mandated to do and it has prepared the ground for onchocerciasis elimination in all APOC countries. I profoundly hope that the momentum can be maintained after the closure of APOC so that onchocerciasis can be eliminated throughout Africa.

One Comment