The Black Death(or bubonic plague to give it its official name) was a great pandemic, peaking in 1346–53, that devastated the realms of Europe, killing millions of people and depleting populations. But is this a disease confined forever to the history books or is it a dormant threat?

The Black Death didn’t just kill people when it first struck in Europe in the 14th century, it made a cultural, political, economic, and religious impact on the masses. Why did this horrible disease strike them? Was it an act of God? Whose fault was it? These are just a few of the many questions that were asked.

The disease devastated entire populations and divided people by their beliefs. The feudal system in England was also broken apart when a majority of the working class population died, forcing survivors to get grafting.

We know now that the true cause of this plague was fleas, not a deity’s wrath.

But what exactly is the bubonic plague?

In simple terms, the disease is caused by the flea-borne bacterium Yersinia pestis. Before the symptoms kick in after being infected, there tends to be a two to six day incubation period while the bacteria multiply inside the body. Once this is over, the sufferer is hit by headaches and chills. The lymph nodes also swell into blister-like lumps famously known as buboes, a classic symptom. Death occurs around two unpleasant weeks later.

The Black Death was a recurring visitor to England. The initial epidemic began to subside perhaps thanks to increased hygiene, quarantining, and cleaner air, only to return again on multiple occasions. Throughout medieval English history we saw a variety of outbreaks including the plague of London in 1665, which was partially put to an end by the Great Fire of London.

Recurrences of the plague aren’t just old history either – which perhaps not everyone is aware of. We saw the disease hit San Francisco in the 1900s, Madagascar, Russia, and China. Thanks to antibiotics such as streptomycin and tetracycline, insecticides, and eventual plague vaccines, the disease was easier to control and expel. But did it vanish completely?

Is the Black Death still with us?

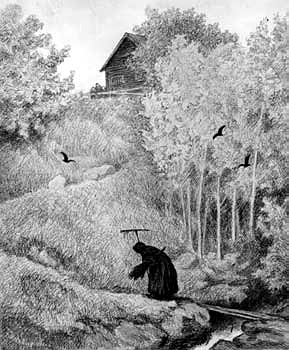

In artwork, the Black Death wasn’t just a disease, it had become a living, breathing creature, personifying the fear of infection. People portrayed the disease as a hooded figure that would shuffle from house to house with the intention of inflicting illness.

You can imagine this was a terrifying idea, especially in such a superstitious era. But, does this being still live amongst us?

The short answer is yes. Times have changed but the bubonic plague still exists. In fact, we still see this disease in many countries, though it seems to attract less notoriety than it once received in Europe.

The Black Death seems to have retreated to its source: Central Asia, although the disease differs slightly to its UK counterpart. Still alive and kicking, the plagues circulates among rodents, including the great gerbil (Rhombomys opimus).

Now, the great gerbil differs from your typical grubby, London rat. They are very social and live in the deserts, in large family burrows. We all associate the Black Death with filthy, sewer dwelling vermin, but unfortunately looks can be deceiving.

Spot the Black Death carrier. The great gerbil (Rhombomys opimus) is a bubonic plague vector. Image courtesy of Yuriy75.

Despite being rather cute and desert-bound, these great gerbils have the ability to influence the spread of the bubonic plague, as does their habitat.

Research in the International Journal of Health Geographics found the geography of the great gerbil’s home influences the spread of the plague. Landscape created paths for the flow of disease, deciding where the great gerbil built its burrows. This finding suggested when it comes to the plague, location and environment are major players.

Could the Black Death make a comeback?

In a commentary for BMC Biology, a researcher suggested climate change could give the bubonic plague the warmth it needs to spread. We’ve seen diseases, such as cholera, break out more readily when the waters warm up. And salmonella food poisoning is most active in summer, thanks to high temperatures boosting the growth of bacterial communities.

It was also argued that climate change may influence rodents carrying the plague. If temperature rises, this may impact vegetation and food sources. With nothing to eat, would these creatures look to human populations for shelter and nourishment? The heat could bring humans and vermin closer together, meaning greater opportunity for infection.

Another growing concern we now face is antibiotic resistance. David Cameron, Prime Minister of England, recently made the comment that antibiotic resistance would take us back to the “dark ages”. This rings true with the bubonic plague, which inflicted so much destruction during the Medieval era.

With this is mind, what’s to say a warmer planet and a reduced ability to treat them won’t encourage exiled diseases to return?.

One Comment