The tree shrew, native to the forests of Southeast Asia, is not a true shrew. These creatures superficially resemble squirrels while anatomically bearing resemblance to both the shrew and lemurs. Therefore classifying these omnivorous creatures is not straight forwards.

Where does this species belong?

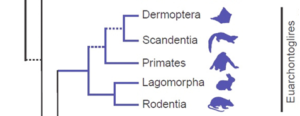

The 17 species of tree shrews, classified into 5 genera, all belong to a specific mammalian order called Scandentia. While this species lies in the same evolutionary group as rodents, they lie within the sister taxon of primates along with flying lemurs. This means that these creatures are more closely related to primates than a rodent which is reflected in their physiology; their hands and feet are well adapted for grasping. It is this feature that is the reason they’ve been used as a model organism for early primate evolution in the past, although this was very much a point of contention.

But why tree shrews ?

“Tree Shrews are primate models for cortical structures, higher than rat and mouse brains”

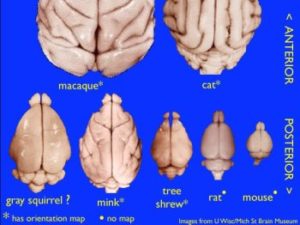

The tree shrews evolutionary proximity to primates is what has made discovering the workings of these creatures brain so interesting. The cortical structures within a tree shrew brain allows for much higher brain functions than that of mouse, such as social emotion and spatial learning memory. Therefore understanding this creature for use as a disease model would produce results closer to clinical conditions and therefore more translatable to humans.

Revelations of the tree shrew’s brain

While it is widely known that the shrew can be used as a primate-like animal model, little is known about the excitatory synaptic transmission in cortical brain areas of the shrew.

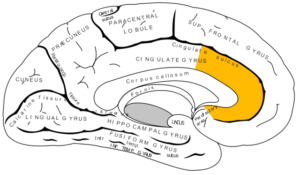

In this study the area of focus was the mechanisms of basal synaptic transmission in the anterior cingulate cortex, responsible for pain perception and emotion.

As seen in mice, glutamate was found to be the main transmitter responsible for fast excitatory synaptic transmission, mediated by AMPA and kinate receptors.

However unlike in mouse models, responses in the post synaptic cells were significantly greater in the tree shrew’s brain, with neurons displaying higher firing frequencies and neuronal excitability. These characteristics displayed are closer to that of primates than mice. You can also see the development of mild brain folding in the tree shrew brains while the rat and mouse brains remain smooth. It’s this folding that allows the brain to have a higher surface area and hold more neurons allowing for higher cortical functions.

Sure tree shrews are weird and cute but why do they matter to us humans?

“The results from Tree Shrew experiments will be more realatable to clinical conditions as their more advanced in evolution”

While plenty of progress is being made, in the understanding of disease and potential treatments, using mouse models translation of these treatments to a clinical setting rarely succeed.

Anatomically the mice’s brains are not capable of the higher brain functions found in humans, producing a translation block between this research and a clinical setting. Using a model with a higher level of brain functions and a brain structure similar to that of humans, would reduce the jump between the model and clinical settings.

As primate models cannot be used for disease and investigatory brain research using a primate-like ancestor, namely the tree shrew, as a model would bridge this gap between rodents and primates, hopefully leading to better clinical outcomes in the future.

Lizzie Anderson

Latest posts by Lizzie Anderson (see all)

- The new protein on the learning and memory scene: Sirtuin 6 - 31st October 2018

- Autism Awareness Week Quiz 2018 - 26th March 2018

- Ghrelin: a new therapeutic target for Parkinson’s? - 20th February 2018

Comments