The biological research community – or at least an influential and vociferous minority of it – is in revolt. Many feel that peer review has become an obstruction to publication rather than a necessary filter and journals have lost sight of their primary function in the dissemination of scientific results. It’s time to separate the publication function from the validation function.

Yes. The invidious influence of impact factors has created an absurd situation in which scientists are judged by where they publish rather than what they publish, and journals – not without the connivance of peer reviewers – may seek to increase the impact of the research they publish by demanding that the data be extended instead of making a decision on the research as submitted.

Pending more radical solutions – as offered, for example, by F1000 Research – biologists are following physicists into the option of preprint servers to make their data available – and thereby establish priority – before submitting to the delays and frustrations of peer reviewed publication.

BioMed Central, like many (though not all) journal publishers, will consider for peer-reviewed publication papers that have already appeared on a preprint server. What else can we do?

Minimizing obstructions

Journals that make their decisions on the basis of the perceived interest and importance of submissions, and not just their soundness, are a prime source of delay and frustration. BMC Biology is one such journal.

Realistically, some delay, and some frustration, some of the time at least, is unavoidable. The pool of referees is limited, and of highly competent and conscientious ones still more so. And then they have to be available, and not completing a competitive grant renewal, or examining a thesis, or on vacation with their families, or…(You referee papers – you fill in the rest).

Portability of peer review helps conserve the time and energy of referees, as well as reducing delay and frustration for authors.

But there is no need for selective journals to exacerbate this with iterative demands, and seven years ago, early in the revolt against current publication practices, we introduced a mechanism, which we called re-review opt-out, for avoiding the iterative reviewing that is a major cause of frustration and focus of complaint.

It’s very simple: we allow authors to choose whether their revised manuscript is seen again by referees. (This doesn’t apply to resubmissions, where the deficiencies of the original submission were serious enough clearly to undermine the validity of the conclusions.) If the authors opt out, their revisions and responses to the reviewers are assessed by the editors.

It seems to work

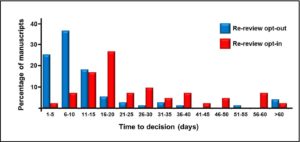

We have written on the pros and cons and pitfalls of this policy, and explained how it works, elsewhere. What we haven’t looked at before is how much time it may save for authors. What can we say about this? Figure 1 summarizes the answer.

The average time for a decision regarding authors opting out of re-review (n=71) is 11 days, and for those opting in (n=41) is 25 days. Or 25% of authors opting out have a decision within 5 days, compared with 2% of those going back to reviewers, and 62% who opt in have a decision within 10 days, compared with 10% for those opting for re-review. And it’s 80% vs 27% at 15 days.

Clearly – look at that tail – we haven’t eliminated delays. Some decisions under re-review opt-out still take a very long time. This is often because methods are incompletely reported, or data are missing, and missing items need to be provided before a final decision can be made; or because data have to be released before final acceptance of the manuscript. It will be interesting to see how far the recent focus on transparency and accessibility of data can compact this distribution.

But of course some decisions are just difficult, and take time and discussion. No getting away from that.

What else can we do?

We have the luxury of a large family of sister journals – the BioMed Central subject-specific series journals, which evaluate papers on the basis of soundness only, as well as a portfolio of journals under the control of outside academic editors with whom we maintain a collegial relationship.

So although as a selective, broad-spectrum journal we make decisions that are based on the perceived interest or importance of submissions, we can mitigate (we hope) the annoyance of a purely editorial negative decision by offering authors a painless transfer, greased by a dedicated transfers desk, for papers we don’t feel able to consider, with full portability of peer review for those papers that don’t seem right for BMC Biology after review.

Portability of peer review helps conserve the time and energy of referees, as well as reducing delay and frustration for authors. And it works both ways. We pass on our reviewers’ comments, and their identities, with their permission, to sister journals. We also consider refugees from other journals pre and post-review, and have an official understanding with eLife and as a first step of integration after the merger of Springer and Nature Publishing Group, with Nature Communications; and an unofficial one with other journals.

What do we mean by interesting?

Different selective journals have different selection criteria. Many insist that any description of a new phenomenon include evidence on its mechanism. We don’t. The basis for The Origin of Species was descriptive. Our favourite more recent example is the discovery of cyclin. (Both however were very firmly based: this is important).

Papers in which all the loose ends have been securely tied up are a rarity and an awesome achievement.

We also try to avoid too rigid an insistence on showing beyond doubt that a paper is ‘right’ at the time of publication. In an established field with an established methodology, this is fair enough. But some fields are inherently messy, and new fields almost inevitably are. There should be some discretion, provided that there aren’t egregious deficiencies that it is well within the authors’ technical capacity to repair in a reasonable time.

Papers in which all the loose ends have been securely tied up are a rarity and an awesome achievement. (Papers in which loose ends have been tucked in out of sight less so.) But it is as important to publish papers that raise questions as to shore up the great edifice of scientific knowledge with papers that answer them.

‘Incremental’ is another term commonly used pejoratively – but a small increment can be important if it shifts a phylogenetic position, or tips the balance between opposing theories.

Rigorous not rigid

We don’t want to sound smug (an occupational hazard for editors). Neither scientists nor editors always get everything right – what we do is too difficult for that.

But we can try to be open-minded and fair, and (within the time constraints of imposed by the need for prompt decisions) helpful.

And on this last point – The statistics in Figure 1 were compiled by Graham Bell, Associate Editor on BMC Biology. He presides over our What is wrong with this picture series, initiated with a view to illustrating some common errors in the way that data are presented or analyzed, causing a paper to fall foul of referees.

We want to help, but we don’t know it all. We’d welcome suggestions for additions to the series.

- The scientific Odyssey: Pre-registering the voyage - 3rd May 2017

- A year of almost anything you can think of in life science – an eclectic pick from BMC Biology - 13th January 2017

- Peer review: opting out - 23rd September 2016

Comments