Generations of scientists have studied the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, a tiny roundworm of only about one millimeter in length, for diverse biological phenomena: the nematode proved ideal to investigate e.g. developmental processes or functions of the nervous system.

For a good reason, sterile worms are used to perform these experiments – artificially freed of any bacterial colonization to exclude external influence on the studied processes.

An interesting article by BMC Editor Penelope Austin sheds a light on past and present of C. elegans’ use as a model system and the role of our publication in this context.

Over time, our lab has undertaken different approaches to look at the lesser known aspects of this heavily used model organism. Here, we are specifically interested in the influence of coevolution among hosts and their associated microbes.

This is why we are convinced that for a full appreciation of an organism, biology must take into account its interplay with the numerous microorganisms naturally populating it.

This is why we are convinced that for a full appreciation of an organism, biology must take into account its interplay with the numerous microorganisms naturally populating it.

This is also true for the classical model organism C. elegans. Thus we have now published the first systematic analysis of a natural nematode microbiome – not only to better understand C. elegans’ life history but to create a new model for the investigation of host-microbe interactions in general.

What did we do?

For our study we joined forces with the group of Marie-Anne Félix from Paris. We initially collected a total of 180 nematode samples at various sites in northern Germany, France and Portugal.

We transferred the bacteria obtained from these animals to sterile worms and could thus demonstrate that the nematodes possess a species-rich bacterial community. Most common are Proteobacteria of the genera Pseudomonas, Stenotrophomonas or Ochrobactrum.

Knowledge of this microbial composition helped us to understand what effects the microbiome has on nematode life history traits: the microbiome increases the fitness of the animals under normal, but also highly stressful environmental conditions.

For example, worms with a natural microbiome are better able to produce offspring at high temperatures than sterile worms. Various Pseudomonas bacteria also help the worms to protect themselves against fungal infections.

To sum it up briefly: Worms with a natural microbiome seem to show higher fitness and reproduce at higher rates – a clear indication of an evolutionary advantage, which the bacteria provide for their host.

What does this mean?

Obtaining a more realistic picture of the nematode’s life history is a scientific achievement per se. But that was not the primary purpose of our study: our aim is to propose a novel and highly efficient model for the new scientific field of metaorganism research.

Considering the advantages of C. elegans as an efficient experimental system – including many tools for functional genetic analysis -, scientists can now use the bacteria identified in our lab to investigate the complex relationships between organisms and their associated microbes in the future.

We assume that bacteria have shaped multi-cellular life from the very beginning. Our new model will help scientists to understand how exactly microbes influence evolution of their host organisms and in what way they determine key organismal functions such as development or immune defence against pathogens.

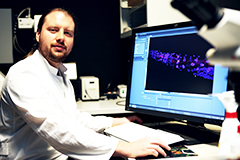

Here is a three-dimensional visualisation of the microbiome of Caenorhabditis elegans by Dr. Philipp Dirksen:

Latest posts by Prof Hinrich Schulenburg & Dr Philipp Dirksen (see all)

- Inside a worm’s gut: the microbiome of C. elegans - 1st June 2016

One Comment