Climate change is predicted to cause sweeping effects on the world’s biomes, but one of the most peculiar will be on certain reptilian species who employ a physiological mechanism called Temperature-dependent sex determination (TSD).

Research published last week in Climate Change Responses has highlighted an anomalous trend in the future sex-ratios of flatback turtles. Where most of the existing literature has warned of an increasing feminized trend in turtles, the rookery of this study has shown quite the opposite. The Cape Domett rookery is a hatching ground for flatback turtles (Natator depressus) located on the northern coast of Western Australia and has been the subject of intensive, long-term study in turtle ecology.

TSD is a type of environmental sex determination only found in reptilian species which lay their eggs out of water, known as amniotes. For contrast, many species (including us!) use chromosomal sex determination – where gender is determined upon conception on a genetic level. TSD is made during the middle-third stage of embryonic development, often only lasting one or two weeks.

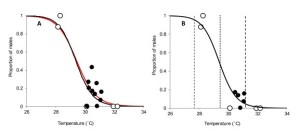

The evolution of TSD has set temperature thresholds for sex-determination, and for turtles males are produced at generally lower temperatures (22.5°-27°C) and females being produced exclusively at temperatures over 30°C. This pattern is reversed in lizards and crocodiles.

It has become increasingly apparent that this poses a serious problem for the species, with the rapid increase in climate change due to both natural variation and the sustained impact of human industrialization causing global temperatures to rise. This could lead to a remarkable shift in the sex ratios of species who use TSD, for turtles a large swing towards feminized primary sex-ratios.

So what’s special about this particular rookery? While the body of literature has currently been focused on the massively feminizing trend in turtle populations, and its trophic effects, this article has found a peculiar masculinized anomaly. Annual variation of temperature has increased in the past 23 years, and has led to an overall trend of cooler winters – the key time during embryonic development of these turtles.

If this trend of variation were to continue, the authors posit that even greater ratios of males to females could be produced out of the Cape Domett rookery. Further monitoring would certainly be required, but this could contribute a measure of balance to the wider trend of feminized turtle population distributions.

Climate change is however a long-term study, and as our authors extrapolated their data out to 2030 and 2070 we return to the female-biased primary sex ratios that have been extensively mapped across many different species.

Marine turtles have adapted to past climate change, however it’s too early to say whether they may cope with anthropogenic global warming – with inherent difficulties in adjusting sites and depth of nests or micro-evolutionary changes in the hormones which regulate temperature thresholds of sex-determination.

This article however provides a framework for future research into these possibilities, and offers a glimpse at the remarkable adage that even in the face of changing environments – life finds a way.

- Where’s the Whale? Quiz - 15th February 2019

- What webs we weave: spiders influence on food webs above and below ground - 7th March 2018

- World Oceans Day 2017 – State of the Seven Seas - 8th June 2017

Comments