Urogenital schistosomiasis caused by the blood fluke Schistosoma haematobium is the main Schistosoma species present in Zanzibar, Tanzania. Zanzibar has two islands, Unguja and Pemba. Each island is divided into small administrative areas called shehias. In 2017, Zanzibar became one of the listed settings targeted for schistosomiasis elimination based on the low schistosomiasis prevalence of <10% elimination by the World Health Organization (WHO). In the 2022 guideline for the control and elimination of human schistosomiasis, the World Health Organization states under Recommendation 4 that health facilities should provide access to treatment with praziquantel, the drug of choice for schistosomiasis, to all infected individuals regardless of age.

For this purpose, the SchistoBreak Project, implemented from 2020 to 2024 on Pemba island, investigated the use of novel adaptive intervention strategies with the aim to eliminate urogenital schistosomiasis in Pemba, Zanzibar. Among the implemented interventions was passive surveillance for urogenital schistosomiasis in primary health care facilities, with the aim to investigate the potential role of health facility involvement in programmatic elimination of schistosomiasis.

The SchistoBreak Project and passive surveillance approach

The SchistoBreak project was implemented in 20 shehias in Pemba, and included annual community- and school-based cross-sectional surveys to identify hotspot and low-prevalence shehias, microtarget interventions and determine the performance of different surveillance and response strategies. In the SchistoBreak project, a hotspot is an area with a S. haematobium prevalence of ≥ 3% prevalence in schoolchildren or with an S. haematobium prevalence of ≥ 2% prevalence in community members aged ≥ 4 years. The Schisto Break protocol is outlined in this paper.

Within these shehias there were 23 health facilities that carried out passive surveillance for urogenital schistosomiasis.

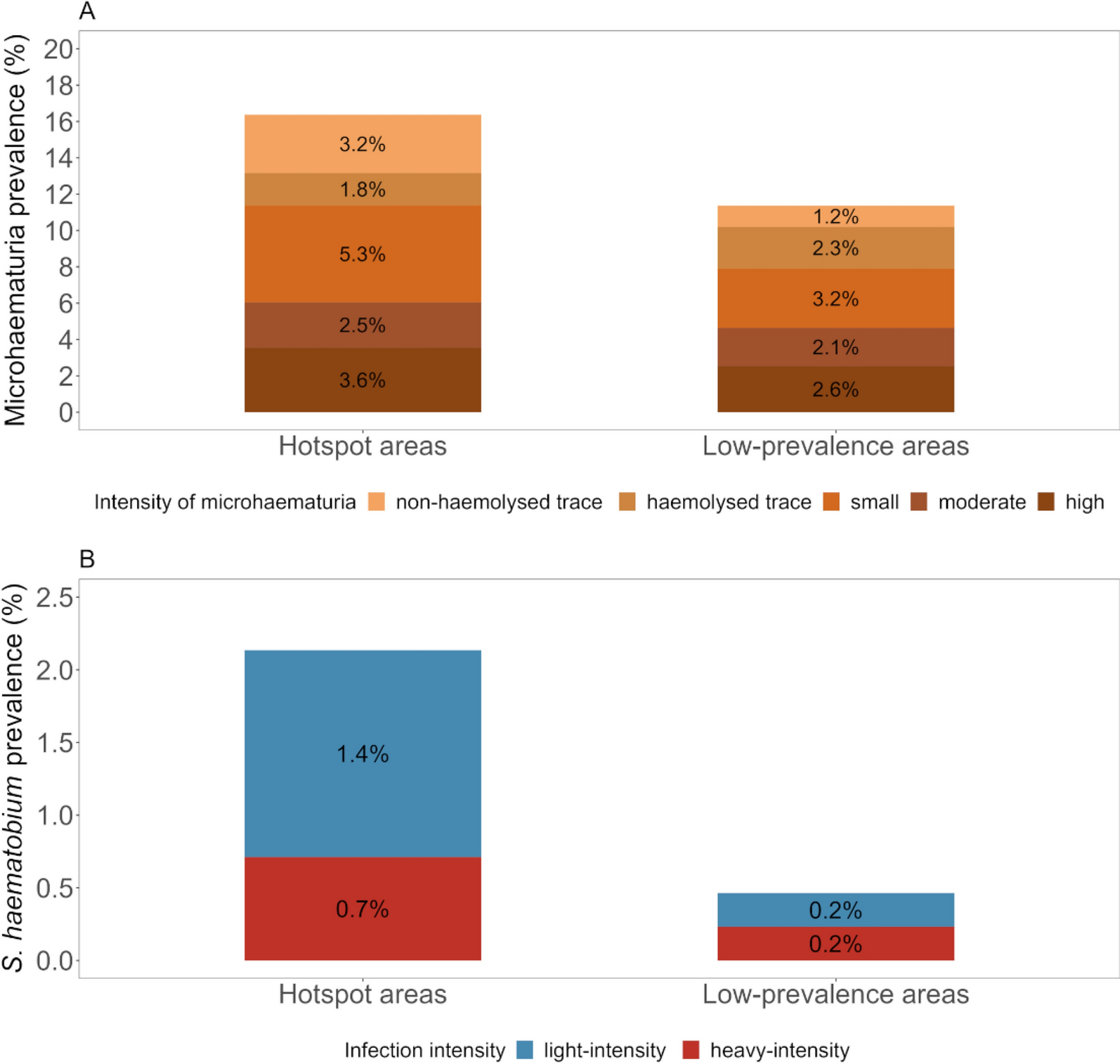

In our study we used a health facility-based mixed-method approach, collecting urine samples to assess the prevalence of schistosomiasis among patients aged ≥ 4 years seeking care in four primary health care facilities: two from low prevalence and two from hotspot shehias. We assessed the prevalence using Hemastix for microhaematuria assessment and using urine filtration microscopy for S. haematobium egg detection. Additionally, we investigated health facility staff’s knowledge and practice and health facilities’ capacities and needs for schistosomiasis diagnosis and management. Our analysis included urine samples from 712 patients, schistosomiasis related knowledge and practices responses from 23 primary health facility staff and data from one focus group discussion (FGD) with 10 primary health care health facility staff.

Passive surveillance and health facilities could play a key role for sustainable schistosomiasis elimination

From our results, 13.3% of the patients were positive for microhaematuria. The S. haematobium infection prevalence (1.1%) identified amongst patients was very similar to the prevalence (0.8%) reported from recent large-scale community cross-sectional surveys in the same area in Pemba. The patients reported with different schistosomiasis related symptoms: pelvic pain, pain during sex, painful urination, bloody urine, genital lesion and vaginal bleeding. All the positive participants we diagnosed were offered treatment with praziquantel.

What we draw from these findings is that, determining the S. haematobium prevalence through longitudinal passive surveillance or during specific periods or days when people are encouraged to attend health facilities for screening might provide an accurate picture of the endemic situation in a given area, and may provide an opportunity to target interventions according to the local prevalence. By treatment of infected individuals, health facilities automatically contribute to a reduction of morbidity and elimination.

The majority of the health facility staff had good knowledge of schistosomiasis, they listed blood in urine, painful urination, pain during sex, and abdominal pain as the typical signs and symptoms of urogenital schistosomiasis. They reported urine as the sample used for diagnosing urogenital schistosomiasis using Hemastix reagent strips or microscopy. All the health facility staff agreed they used praziquantel to treat patients whom they diagnosed positive for urogenital schistosomiasis. Here, it is important to point out that the SchistoBreak project provided bi-annual training on the management of urogenital schistosomiasis to health facility staff. Nonetheless, our findings imply that health facilities may serve as a reinforcement in the symptomatic identification, testing, and treatment of schistosomiasis.

From the FGD, health facility staff expressed their interest in actively participating in passive surveillance of urogenital schistosomiasis. They pointed out they could play an important role in monitoring and reporting cases via identifying, testing, treating, and carrying out specific education in the health facility and the community while working in collaboration with community heads. They added that they would be able to identify and report outbreaks. Importantly, they also expressed a need for improvement in several areas of their health facility highlighting more training for capacity building, provision of more efficient diagnostic tools and praziquantel, and the need for infrastructural improvement. They said:

“The PHCU can play a role, for example, when the patient who has the sign first of all they come to the PHCU so when they come here, it is our responsibility when she tells us the symptom you have to check and when you confirm you have to treat the patient so that we can play a big role to make sure that we treat, we give them exact treatment and check out patient” (respondent 10).

“If we are using microscope we are going to see the eggs. How many is there, meaning we are going to know much. But if we are using Hemastic, we only know the patient is positive but we do not know like how” (respondent 12)

“I need to add something, when we using microscope, we are going to confirm the diagnosis. It is not like Hemastix that only detects blood in the urine and it is not every blood in the urine that is kichocho, so then if we use microscope we will get confirmation that this is kichocho” (respondent 10).

(PHCU = Primary health care units. These are the first-line health facilities in Tanzania)

This implies that adequate and regular training of health facility staff in the recognition of signs and symptoms and the management of schistosomiasis is warranted.

It needs to be noted that reagent strips to detect microhaematuria lack specificity and that standard egg microscopy has a limited sensitivity to detect S. haematobium infections, particularly in near-elimination settings where infection intensities are mostly low. There is a pressing need for the development of more sensitive and specific point-of-care diagnostic tools, which can be supplied together with praziquantel to health facilities in Pemba and other African regions, should health facilities play a role in routine treatment of schistosomiasis, as recommended by WHO.

Comments