Malaria is a serious disease caused by parasites in the genus Plasmodium and is typically transmitted by mosquitos. Though there have been advances in the prevention of the disease, each year sees a large number of cases. In 2021 alone, there were an estimated 247 million cases and 619,000 deaths caused by malaria. Part of the issue is that the parts of the world most affected by it are often poorer and lack the infrastructure to confront the issue.

For example, although malaria is still a major economic and health concern in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) in Southeast Asia, the area has seen a stable decrease in incidence of the disease, save for forested regions. Within these woodlands, marginalized populations are still exposed to malaria, and the rural area presents challenges in disease prevention. As mosquitos are active during the day, specialized bed nets are ineffective, and many of the forest-goers living in the area often use temporary shelters. Policymakers have also been reluctant to implement more aggressive strategies due to feasibility concerns.

In a recent article published in Malaria Journal entitled, Community engagement among forest goers in a malaria prophylaxis trial: implementation challenges and implications, Conradis-Jansen et al. highlight the difficulties and effectiveness of conducting a randomized controlled clinical trial in the region. For the study, they compared anti-malarial chemoprophylaxis with artemether-lumefantrine (AL) to a multivitamin, used as a control.

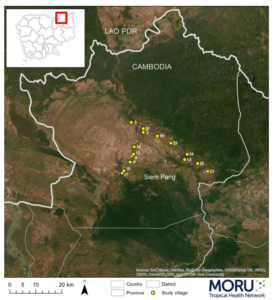

The trial was conducted between March and November 2020 in northeast Cambodia, in the Siem Pang District, Stung Treng Province. A national census estimates that the district has a population of approximately 26,000.

The authors invited those between the ages of 16 and 65 planning an overnight trip in the forest to participate in the study. They write that “AL was provided as 4 tablets twice daily for 3 consecutive days, followed by twice-a-day weekly dosing for a maximum of 4 months. A multivitamin was provided as 1 tablet twice daily for 3 consecutive days and then weekly thereafter for the same duration.” (The full trial protocol is available here.)

A major challenge Conradis-Jansen et al. faced was ensuring the participants were motivated to comply with the procedures and come to monthly follow ups. The authors therefore adopted several engagement strategies.

- Holding meetings with policymakers, local authorities, participants, and the general community. These meetings were open to everyone, regardless of socioeconomic status, and were conducted before and during the trial. The authors presented information about their planned protocol, but these were far from one-way lectures. They encouraged those in attendance to speak up and share their opinion, and incorporated recommendations and concerns into their plans.

- Co-developing informational material with stakeholders. Due to various literacy and educational levels, as well as language differences, the authors worked with key stakeholders, such as local health officials and community leaders, in order to create simple and effective messaging designed to answer questions about malaria and the trial. Leaders from ethnic minority groups were also selected to make sure members of those groups were not inadvertently excluded from the research and that language barriers would not prove to be obstacles.

- Building trust with the community. Those working on the trial formed a “joint engagement team” together with stakeholders, which held additional meetings to help address community concerns and build trust with the forest-goers.

- Recruiting and involving members of the forest workers. Forest-goers travel in groups of 10 or less and are typically led by a senior member. These leaders were recruited as volunteers to ensure the group complied with the trial and ingested drugs as directed, and if unable or unwilling to take on the responsibility, another member of the group was selected.

So, what did this trial find? And did the community engagement appear to bolster participation?

In total, 1,480 participants joined the study. In another study, published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, the author group reports that 738 were given the AL, while 742 received the multivitamins. During follow up, 19 individuals taking AL had malaria, compared to 123 in the control group. And ultimately, 1,242, or about 84% of participants, completed the study.

These finding show that chemoprophylaxis with AL can be effective at reducing the risk of contracting malaria, and also highlight how community engagement, codesign and participatory approaches can strengthen disease prevention strategies, enabling them to be effectively implemented in more rural regions and marginalized communities.

Comments