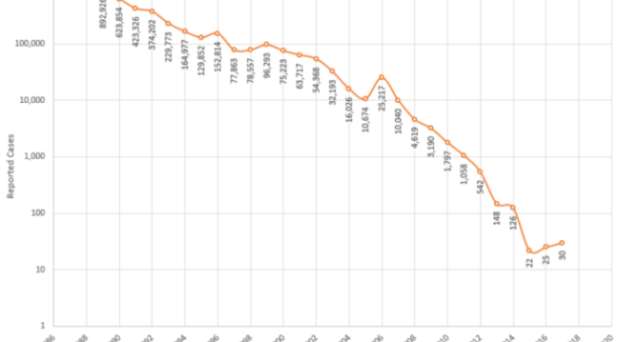

In January this year, the Carter Foundation announced that in 2022 annual cases of Guinea worm disease reached an all-time low. Following the report of 15 cases worldwide in 2021, only 13 human cases of Guinea worm disease were reported in 2022, six in Chad, five in South Sudan, one in Ethiopia and one in the Central African Republic, pushing the disease nearer to extinction.

WHO has now certified 200 countries as free from Guinea worm disease, the latest being the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in 2022.

The Carter Centre

The Carter Foundation, co-founded by former US President Jimmy Carter and his wife Rosalynn in 1986, is recognised as a global leader in the fight against neglected tropical diseases. In addition to the Guinea worm Eradication Programme, it has programmes focussed on river blindness, trachoma, schistosomiasis and lymphatic filariasis.

What is Guinea worm disease?

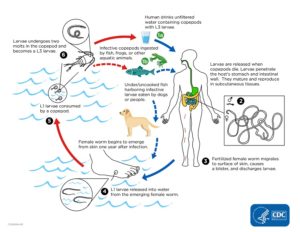

Dracunculiasis, commonly known as Guinea worm disease, is a debilitating condition caused by the parasite Dracunculus medinensis. The mature female worms migrate, usually to the legs or feet, then form blisters which swell with fluid and eventually burst, causing an intense burning sensation. If the infected limb is immersed in water to alleviate the pain, thousands of larvae are released into the water. These blisters, which can last many days, can become infected with bacteria causing abscesses and leading to complications that can, occasionally, be fatal.

If Guinea worm larvae are ingested by water fleas the worm’s life cycle continues. Infected water fleas, accidentally swallowed by people drinking contaminated water, carry the parasite to new human hosts.

The Guinea Worm Eradication Programme

2022 marked 36 years since this programme started. At that time, about 3.5 million human cases occurred annually in 21 countries in Africa and Asia. Although there is no vaccine or medicine available for this disease, remarkable progress towards elimination has been achieved by the implementation of a variety of strategies, including:

- Education and involvement of communities in endemic areas.

- Removal of water fleas from drinking water by distributing filters for water containers and straw filters for water drinking.

- Cleaning and bandaging affected areas and gradual removal of worms by winding round a stick.

- Protecting water sources by preventing infected people and animals from entering the water.

- Use of a larvicides in stagnant water sources.

- Surveillance and rewarding the reporting of potential cases in humans and animals.

Overcoming setbacks

In addition to the worrying report of human cases reappearing in Chad after 10 years absence, several cases of Guinea worm infections were identified in domestic dogs. If these infections were also caused by D. medinensis it was feared that dogs would act as reservoir hosts for the parasite, and disease eradication would prove more difficult. In 2018, Kristian Magori’s BugBitten blog described how genotype comparisons of Guinea worms from dogs and humans in Chad, Ethiopia, Mali and South Sudan did revealed them to be the same species.

While humans become infected with the worms by drinking water contaminated with infected water fleas, experiments showed this to be a very unlikely route to infection in dogs. Instead, dogs may have been infected by eating infected amphibians or fish that could be acting as paratenic or fish transport hosts (with infected copepods in their guts). When this was recognised, interventions that could prevent dog infections were put in place. These included, ensuring fishermen do not feed fish scraps to dogs, tethering dogs to prevent them entering water containing water fleas, and treating the water bodies with the larvicide Temephos (Abate®).

Until dog infections can be stopped, there will always be the possibility that the life cycle of the Guinea worm continues, water sources remain contaminated by infected copepods, and dracunculiasis is not eradicated.

The last leg

The 2022 Guinea worm summit, held in Abu Dhabi, pledged to support a programme to eradicate Guinea worm disease by 2030. This objective has been postponed several times in the past. Let us hope control measures are effective in the remaining four endemic countries, and eradication of a second human parasitic infection will finally be achieved.

Comments