The troubling rise in cases of febre amarela has Brazilians queueing around vaccination centres around the country, as people urgently seek protection from the infection. Yellow fever is a viral haemorrhagic disease transmitted by the bite of a mosquito, and manifests with non-specific symptoms such as fever, muscle pain, nausea and vomiting. Although most recover after this, around 15% of people go on to the more toxic phase: a characteristic yellowing of the skin (jaundice), vomiting and bleeding which can result in death in half of cases. And although no antiviral drugs exist against yellow fever (treatment is symptomatic), it is a vaccine-preventable disease.

In South America, there are two disease cycles. In urban yellow fever, the virus is transmitted from person to person through the bite of Aedes aegypti, which thrives in domestic settings. This cycle, which could potentially cause the highest number of casualties, has not been recorded in Brazil since 1942. In sylvatic yellow fever, ‘wild’ mosquitoes (Haemoagogus and Sabethes genera) transmit the virus between monkeys in forested areas; people are accidentally infected when they enter these ecosystems.

Fractional dosing: making the most of vaccine stocks

According to Brazil’s Ministry of Health, sylvatic transmission is the source of 213 confirmed cases of yellow fever in the country from the surveillance period between July 2017 and January 2018. Unfortunately, 81 people have died so far, while another 435 cases remain under investigation. Residents of the high risk areas (currently Sao Paulo, Minas Gerais, and Rio de Janeiro) are advised to avoid wooded areas and recreational parks, unless they have been vaccinated.

There is a safe and effective vaccine against yellow fever, a single dose of which confers life-long immunity. Within 30 days of receiving the vaccine, 99% of vaccinated people are protected. In Brazil, the magnitude of the yellow fever outbreak has forced health authorities to fractionate the vaccine into smaller doses to increase population coverage in risk areas: since 2017, approximately 74,4 million doses have been administered.

What are the effects of a partial dose?

In ‘fractional dosing’, the World Health Organization says one fifth of the vaccine can provide the same protection as the full dose for at least 12 months. But there is evidence it could be even longer. A study conducted in 2017 by Bio-Manguinhos/Fiocruz, followed up 319 participants out of 900 that had been immunized back in 2009 with different doses of the vaccine. Their results confirmed that a reduced fraction can offer full protection for at least 8 years, further supporting this vaccination strategy. However, a full dose is still given to children between 9 months and 2 years, pregnant women in high-risk areas, and travellers to countries that require a vaccination certificate. It should also be noted that although the vaccine is considered to be safe, it is contraindicated in some cases, and medical guidance should always be provided.

Fractional dosing is recommended to control outbreaks, but vaccination needs to be a part of a larger control strategy. In 2017, several Brazilian health societies wrote an open letter to the authorities, addressing the need to take stronger action against an imminent risk of yellow fever urbanization and its devastating consequences. They urged the establishment of short- and medium-term policies, including the reinforcement of both vaccine production and strict vaccination campaigns, as well as updated surveillance data that would allow control measures to be changed as needed. Furthermore, the letter advocated for a collaboration between different institutions including health authorities, research centres, and the media.

The environmental impacts of the outbreak

“Yellow fever exterminates all 17 families of howler monkeys in Horto” was the unfortunate headline published in a Brazilian daily newspaper early in January this year. According to a researcher they interviewed newspaper, 86 monkeys lived in the forested city park before the virus arrived. Health authorities closed the park after they were alerted of their first animal death back in October 2017: monkeys are more sensitive than humans to the virus, and the event flagged up the circulation of yellow fever in the area. But this is not something new. Throughout Brazil, primates of different species have been affected by the emergence of yellow fever, in some cases decimating entire populations. Since the outbreak started in July 2016, 617 primates have fallen ill or dead with the virus. Cities like Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, which are part of the current outbreak, are reporting primate casualties.

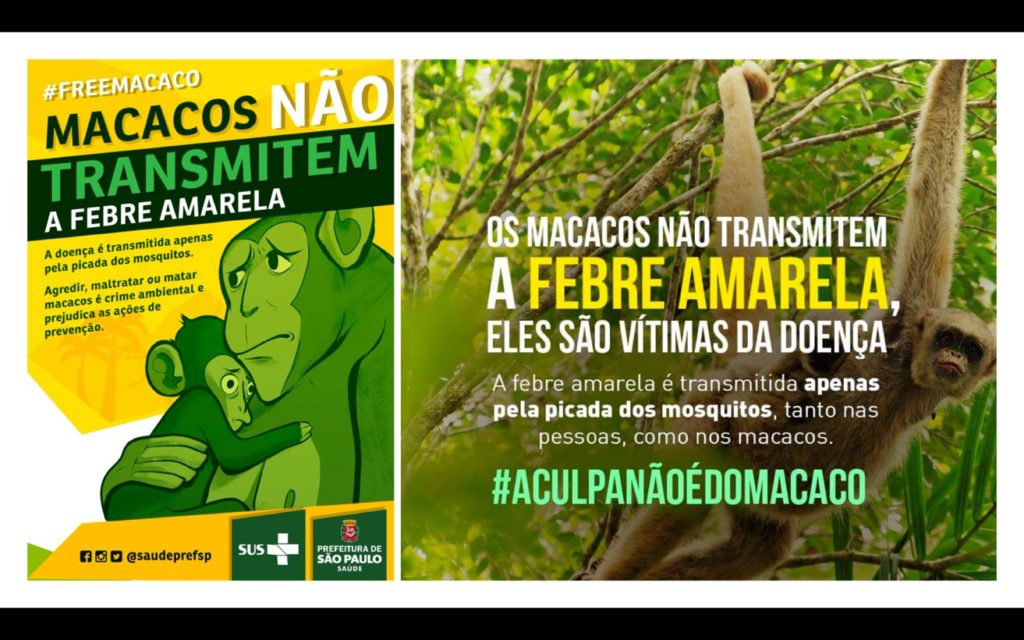

Sadly, not only the virus is killing the monkeys. As the public is aware these animals can also get yellow fever, some people poison or beat them to death out of fear they will give them disease. Apart from disseminating information on yellow fever vaccination and prevention, education campaigns by health authorities are reminding Brazilians that it is the mosquito that transmits the yellow fever virus, and not the monkeys. Their protection is particularly valuable since, aside from their ecological importance, the presence of the primates helps authorities in their surveillance of this disease.

Comments