Every three years, hundreds of heartworm researchers, veterinarians and students mark their calendars for the Triennial Heartworm Symposium, a scientific meeting that convenes the world’s leading experts on heartworm disease in sharing the latest information and research. This symposium is one of the most important functions in the charter of the American Heartworm Society (AHS) as we fulfill our mission of leading the veterinary profession and the pet-owning public in the understanding of heartworm disease.

The 2016 symposium, which was held September 11-13, 2016, in New Orleans, included more than 50 presentations, panel discussions and posters covering a variety of topics, from the pros and cons of different heartworm treatment protocols, to the latest insights on mosquito vectors and blocking strategies, to updates on heartworm resistance and diagnostic techniques. The presentations and panel discussions confirmed the complexity of understanding, preventing and treating heartworm disease, and affirmed why its persistence continues to confound those of us who work to prevent, diagnose, and treat it every day. The Proceedings, published in Parasites & Vectors, features 28 peer-reviewed papers from the Symposium.

What is Heartworm Disease?

Heartworm disease is a serious and potentially fatal disease in pets in many parts of the world. It is caused by foot-long worms (Dirofilaria immitis) that live in the heart, lungs and associated blood vessels of affected pets, causing severe lung disease, heart failure and damage to other organs in the body. Heartworm disease affects dogs, cats and ferrets, but heartworms also live in other mammal species, including wolves, coyotes, foxes, sea lions and – in rare instances – humans.

Dogs: The dog is a natural host for heartworms, which means that heartworms that live inside the dog mature into adults, mate and produce offspring. If untreated, their numbers can increase, and dogs have been known to harbor several hundred worms in their bodies. Heartworm disease causes lasting damage to the heart, lungs and arteries, and can affect the dog’s health and quality of life long after the parasites are gone. For this reason, prevention is by far the best option, and treatment – when needed – should be administered as early in the course of the disease as possible.

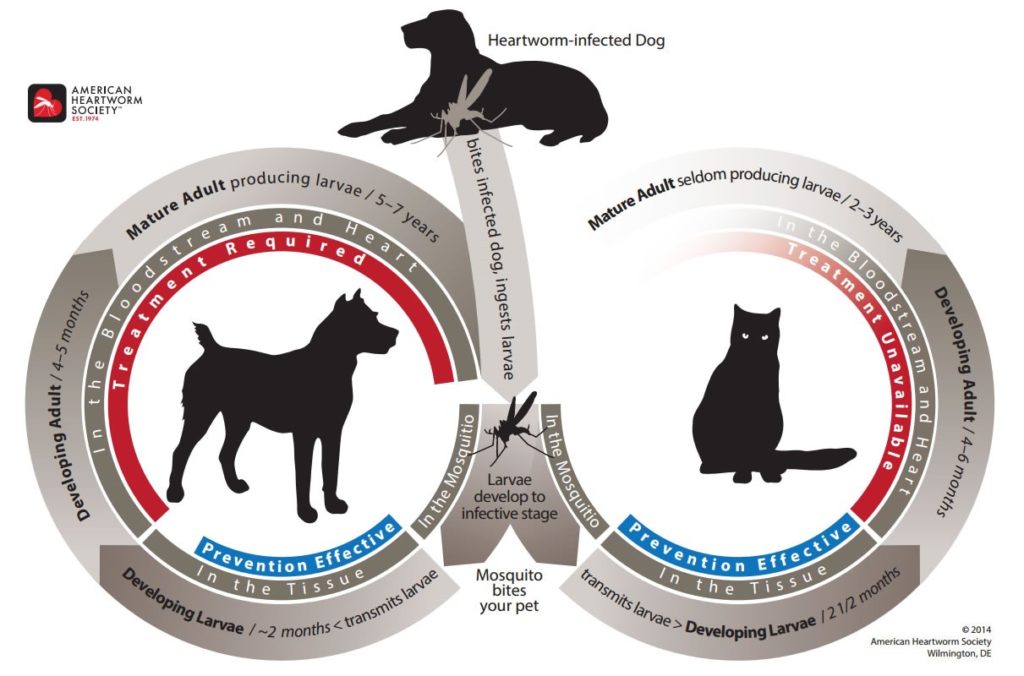

Cats: Heartworm disease in cats is very different from heartworm disease in dogs. The cat is an atypical host for heartworms, and most worms in cats do not survive to the adult stage. Cats with adult heartworms typically have just one to three worms, and many cats affected by heartworms have no adult worms. While this means heartworm disease often goes undiagnosed in cats, it’s important to understand that even immature worms cause real damage in the form of a condition known as Heartworm-Associated Respiratory Disease (HARD). Moreover, the medication used to treat heartworm infections in dogs cannot be used in cats, so prevention is the only means of protecting cats from the effects of heartworm disease

The Heartworm Life Cycle

The mosquito plays an essential role in the heartworm life cycle. Adult female heartworms living in an infected dog, fox, coyote, or wolf produce microscopic baby worms called microfilaria that circulate in the bloodstream. When a mosquito bites and takes a blood meal from an infected animal, it picks up these baby worms, which develop and mature into “infective stage” larvae over a period of 10 to 14 days. Then, when the infected mosquito bites another dog, cat, or susceptible wild animal, the infective larvae are deposited onto the surface of the animal’s skin and enter the new host through the mosquito’s bite wound. Once inside a new host, it takes approximately 6 months for the larvae to mature into adult heartworms. Once mature, heartworms can live for 5 to 7 years in dogs and up to 2 or 4 years in cats. Because of the longevity of these worms, each mosquito season can lead to an increasing number of worms in an infected pet.

What are the signs of heartworm disease?

Dogs: In the early stages of the disease, many dogs show few symptoms or no symptoms at all. The longer the infection persists, the more likely symptoms will develop. Active dogs, dogs heavily infected with heartworms, or those with other health problems often show pronounced clinical signs.

Signs of heartworm disease may include a mild persistent cough, reluctance to exercise, fatigue after moderate activity, decreased appetite, and weight loss. As heartworm disease progresses, pets may develop heart failure and the appearance of a swollen belly due to excess fluid in the abdomen. Dogs with large numbers of heartworms can develop a sudden blockage of blood flow within the heart leading to a life-threatening form of cardiovascular collapse. This is called caval syndrome, and is marked by a sudden onset of labored breathing, pale gums, and dark bloody or coffee-colored urine. Without prompt surgical removal of the heartworm blockage, few dogs survive.

Cats: Signs of heartworm disease in cats can be very subtle or very dramatic. Symptoms may include coughing, asthma-like attacks, periodic vomiting, lack of appetite, or weight loss. Occasionally an affected cat may have difficulty walking, experience fainting or seizures, or suffer from fluid accumulation in the abdomen. Unfortunately, the first sign in some cases is sudden collapse of the cat, or sudden death.

_______________________________________________________________

In parts 2 and 3 of this post, we’ll report on a few of the highlights from the AHS Triennial Symposium in a Q&A with some of the symposium’s speakers and moderators.

For more information about the American Heartworm Society, please visit our website at https://www.heartwormsociety.org/.

Comments