News of West Nile virus (WNV) first hit the popular press in 1999 when cases of infection in humans were identified in Queen’s, New York, USA. It quickly spread across the whole of the US, carried by infected birds, and 3 million people are estimated to have been infected between 1999 and 2010. Since then more outbreaks have occurred in the US, typically in August and September. However, sporadic outbreaks occurred in Europe before this, and still do. Its geographic range is expanding in Europe, causing increasing numbers of epidemics.

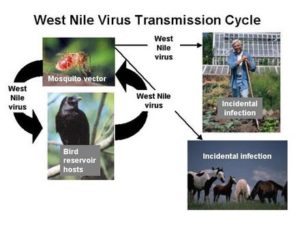

WNV was first discovered in the West Nile district of Uganda. It is a flavivirus that is transmitted by mosquitoes in the genus Culex, that have fed on infected birds. While this is the natural transmission cycle, horses and humans can also be infected. Most humans infected with the virus are symptomless, but it can cause a fever, headache and rash (West Nile Fever). However, in less than 1% of cases the virus infects the nervous system causing severe symptoms, that can result in death. Horses are particularly susceptible to infection, and it can be fatal in up to 40% of cases.

Culex mosquitoes

The common house mosquito, Culex pipiens, has a widespread distribution, which includes Europe, the Middle East, North and parts of South America. Two subspecies, Cx. pipiens f. pipiens and Cx. pipiens f. molestus were thought to form a complex but microsatellite imaging suggests that, in Northern Europe at least, there is no evidence of gene flow between the two, suggesting they are distinct species.

These mosquitoes also differ in their behaviours. Cx. p. f. pipiens predominantly bites birds, is cold-tolerant and hibernates in the winter. In contrast, Cx. p. f. molestus bites rats, mice and humans, is cold-intolerant and can breed all year round due to its habit of living in warm, underground locations. It is commonly known at the London Underground mosquito though it is also common in the sewers of New York.

Some infected birds develop levels of circulating WNV sufficient to transmit the infection to bird-feeding mosquitoes that can then pass on the virus when biting again. However, humans and horses are considered dead-end hosts because viraemia does not develop to a level that allows transmission back to mosquitoes.

Cx. p. f. pipiens is the major vector for WNV in Europe but, because this species hibernates in winter and mosquito biting does not occur then, the source of new infections each summer is a puzzle.

West Nile virus in Europe

A neuroinvasive lineage of WNV, WNV-2, was first reported in Hungary in 2004 and subsequently spread, causing outbreaks in Greece, Austria, Serbia, Italy and the Czech Republic. While WNV is usually transmitted by Culex pipiens in Europe, WNV-2 was found in Cx. modestus in the Czech Republic.

Disease outbreaks are associated with the peak mosquito biting seasons in summer and autumn, and the annual source of new infections has been uncertain. How does WNV-2 overwinter?

One clue to this problem was the discovery of WNV-2 in the egg rafts and pupae of Cx. pipiens during a small scale entomological study in Vienna. This finding showed that the virus could be transmitted vertically to the next generation of mosquitoes via a female’s infected eggs.

Could the virus persist in overwintering mosquitoes? With this in mind, a long-term study of mosquitoes was conducted in South Moravia between 2011 and 2017.

A long-term study

Based on their hypothesis that the virus overwintered in mosquitoes, Norbert Nowotny and colleagues conducted a 7 year study and recently published their findings in Parasites and Vectors.

Mosquitoes resting on the walls and ceilings of cellars, including a castle, wine cellars, pension homes and a water tower, were collected and identified. After extracting RNA from pooled mosquito homogenates, it was tested for the presence of flavivirus RNA. Over all they collected 28,287 mosquitoes belonging to 3 species, Cx. pipiens being present in overriding numbers (they did not separate Cx. f. pipiens from Cx. f. molestus).

For the first 6 years of their study, they were unable to detect the presence of flavivirus RNA in any of their samples. However, in February 2017, three Cx. pipiens samples tested positive. The strains were identical, even though they were collected from different locations, with 97% nucleotide identity to the WNV strain circulating in the area.

Conclusions

The authors suggest their inability to detect WNV-2 in samples earlier in their study may be due to the low endemicity of this strain in the Czech Republic until 2013. They conclude that their finding supports the hypothesis that this virus persists in overwintering mosquitoes in Europe and that re-introduction is not necessary. The virus can be transmitted to the next generation of mosquitoes via their eggs and the next generation will then infect the local bird population to maintain the cycle.

Clearly two positive samples are a proof of concept, but confirmation that WNV persists in overwintering mosquitoes in other parts of Europe would be valuable.

Comments