Insecticide treated bed nets remain one of our most important tools for controlling the Anopheles mosquitoes that carry the malaria parasite. Bed nets work so well because they target mosquitoes that prefer to feed on humans and to come indoors to bite and rest. This also means that we are limited in the types of chemicals we can use in their control. Only one class of insecticide (pyrethroids) are approved for use in bed nets. This strict restriction on chemicals used in bed nets is important for making sure these insecticides are safe, but it also creates a problem. The intensive use of one or two classes of chemical can rapidly lead to the evolution of resistance and the list of insecticides we can switch to is very short. It is becoming disturbingly common place that mosquito populations are reported to be resistant classes of chemicals that are considered safe enough to be applied in homes.

How do we determine if a population is resistant? Insecticide Resistance (sometime abbreviated as IR) is difficult to quantify. The effectiveness of an insecticide can depend on lots of factors, but obviously the method and duration of exposure is at the top of the list. In order to make resistance measurements comparable the WHO has created a series of extremely specific assays.

This kind of standardization is important for the operational realities of control and this type of information is used to design a resistance management strategy. If a population exhibits less than 90% mortality they are considered to be insecticide resistant. With indications of wide spread resistance using these types of standardized assays (and the accompanying identification of resistance alleles in the population) we appear to be teetering on the brink of a serious crisis. It seems to be merely a question of when our front line tools for control will be useless. However, this bleak assessment depends on a simplifying assumption: that exposed survivors are going to transmit malaria. What if they don’t?

This is what Viana and colleagues asked in a recent study published in PNAS. They hypothesized that even though these mosquitoes initially survived the exposure to pyrethroids, that exposure would decrease the ability of these survivors to transmit. Using a combination of bioassays and epidemiological modelling they determined how much these survivors would potentially contribute to malaria transmission.

They began by measuring the long term survival of the mosquitoes not succumbing to the WHO cone test. In this assay, mosquitoes were exposed to a bed net using a cone for 3 minutes. Knockdown was counted after 1 hour and mortality is tallied after 24 hours.

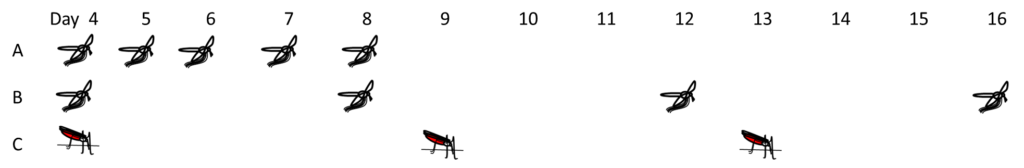

To add additional realism, they used three different methods for exposing the mosquitoes. Exposure A mimicked the exposure pattern of a female that tried to take a blood meal unsuccessfully on 5 consecutive nights. Exposure B mimicked a less persistent females that unsuccessfully attempted to take a blood meal through the net every 4 days. The last exposure pattern, C, mimicked the worst case scenario from the control perspective: a female that successfully feeds through a treated bed net every four days.

The survival of these two resistant strains was tracked over several days. After 24 hours large proportions of the resistant strains were still alive (up to 40% of the TOR strain and up to 97% of the TIA strain). However, when survival was tracked over 40 days, these exposed mosquitoes continued to exhibit much lower survival than controls (mosquitoes from the same strain that went through the whole assay without insecticide). When this delayed mortality effect was combined with the immediate mortality epidemiological modelling indicated that the proportion of infectious bites the resistant populations could deliver (a measure of transmission potential) was halved. In other words, adding a delayed mortality effect lead to output which suggests that control with insecticide treated bed nets can still be achieved even on resistant populations.

What does all this mean for our resistance crisis? It doesn’t mean the problem is going away. Continuing to expose partially resistant populations is going to select for further resistance. However, it does indicate that IR might not be as disastrous as we would have believed previously. Our bed nets might continue to work even though they aren’t immediately killing resistant females. The news could get even better. Here it was assumed that a living mosquito was a viable vector. It may be that despite being able to survive, surviving females may be less competent to transmit malaria for other reasons. Additional work on investigating the behavior and competence of exposed IR lines could greatly improve our understanding of transmission in this new world of resistant populations.

Comments