River blindness, or onchocerciasis, is a largely tropical disease caused by the parasitic worm, Onchocerca volvulus. It is estimated that 17-25 million people are infected, 300,000 of these are blind and others suffer debilitating symptoms such as intense itchiness, loss of skin pigmentation and subcutaneous nodules.

The majority of infections occur in sub-Saharan Africa but transmission also occurs in the Yemen and the Americas; the parasite was spread to the latter countries as a result of the slave trade.

The common name, river blindness, refers to the life cycle of the parasite as it is transmitted by biting blackflies of the genus Simulium, whose larvae develop in fast flowing streams and rivers. Parasite transmission occurs in proximity to the vector’s breeding sites. Female blackflies need a blood meal in order to produce a batch of eggs. If infected with the third stage larvae of O. volvulus the parasites will move into the bite wound whilst the blackfly feeds. It usually takes several infective bites to set up an infection.

The worms develop into adults in nodules deep in the skin and mature females release 500-1000 larvae, known as microfilariae, daily for up to 15 years. These microfilariae migrate in the skin ready to be taken up by another feeding blackfly. It is the dying microfilarae that cause the disease symptoms. The symbiotic Wolbachia bacteria that they carry are released into the skin and a protein on the surface of the bacteria initiates an inflammatory response.

In the eye they cause the cornea to become progressively more opaque, finally causing blindness.

There is no vaccine against onchocerciasis but a very effective drug, ivermectin, inhibits the production of microfilariae. Unfortunately it does not kill the adults and so, as the females are long lived, the drug has to be taken for many years. Following its discovery in the 1980s the pharmaceutical giant Merc decided to donate ivermectin (as MECTIZAN) for use in mass drug administration programmes (MDPs).

Transmission in the Americas

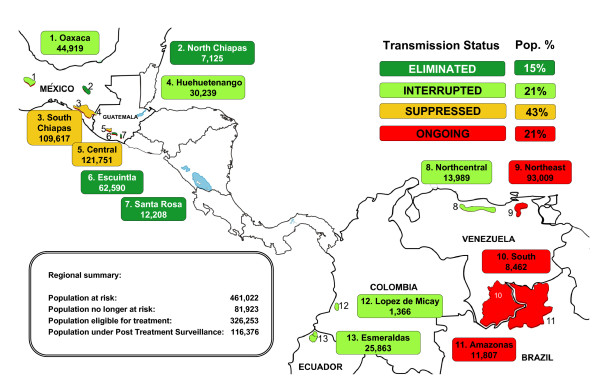

In the Americas, onchocerciasis was endemic in six countries.

A large consortium, led by the Carter Foundation, supported the goal set by the Pan American Health Organisation to fulfill the criteria set by WHO for the elimination of onchocerciasis by 2015. These criteria were both epidemiological and entomological.

In order to declare elimination of onchocerciasis, examination of at least 6000 blackfly vectors must be performed to demonstrate that none are infected with Onchocerca larvae. This is undertaken three years after the original determination of lack of transmission and cessation of the mass drug administration programme. So far only Columbia and Ecuador have achieved WHO elimination status.

The current situation in Mexico

In Mexico there were three foci of transmission, Northern Chiapias, Southern Chiapas and Oaxaca. Mass drug treatment was started in 1997 and Mario Rodríguez-Pérez and colleagues have performed surveillance studies to monitor progress towards elimination. Three years ago transmission appeared to have stopped and mass drug administration ceased. This summer they reported that the criteria for declaration of elimination from these Mexican foci had been met.

Their study involved teams of two people, one acting as human bait whilst the other was the blackfly collector. Collections of flies were made for 50 minutes every hour and flies were immediately take to field stations for identification of the vector blackfly, Simulium ochraceum s.l. Surveillance was undertaken in 18 areas in the previously endemic foci; one team working in the community and the other in the coffee plantations. This occurred throughout the peak transmission season (December to May), which coincided with peak numbers of blackflies.

Blackfly vectors were dissected and pools of flies subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to identify the presence of O. volvulus DNA.

Taking into account the number of flies caught and the number of flies that were infected, the seasonal transmission potential was calculated.

They examined an admirable total of 108,232 blackflies and none were found to contain Onchocerca DNA. The authors therefore declare that their data suggests that, three years after the cessation of mass Mectizan administration, no parasite-vector contact is occurring in these three foci of transmission. Mexico has now applied to WHO for verification of the elimination of this neglected tropical disease.

Could onchocerciasis return to Mexico?

Because their surveillance only took place during part of the year, annual, as opposed to seasonal, transmission potential could only be estimated. This estimated value was also zero thus they concluded transmission values were well below the transmission breakpoint.

Furthermore they argue that transmission is unlikely to reoccur in Mexico as these infection foci are isolated. Simulium ochraceum does not migrate seasonally so blackflies from other countries are unlikely to fly in. Likewise, migrant workers from across the border do not pose a threat as transmission has also ceased in Guatemala. However, they suggest surveillance work should continue for another three years and the Mexican Ministry of Health recognize clinical and entomological surveys should continue periodically.

Although the original objective of elimination from all Latin American countries by 2015 has not been met transmission is only continuing in foci in Brazil and Venezuela.

Prospects for global elimination

The situation with respect to onchocerciasis elimination in Africa presents a much greater challenge. However, reports that mass administration of ivermectin on an annual or biannual basis is interrupting transmission in Uganda, Northern Sudan, Mali, Senegal and Nigeria are promising, suggesting this goal is feasible.

Clearly there is hope for the future for populations living in areas endemic for this debilitating disease.

Comments