One in 6 people worldwide are exposed to infection by a large group of parasitic or bacterial infections that disable, disfigure and debilitate, killing 500,000 per year. In contrast to the three major infectious diseases, malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS, these Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD) received little attention from the media and efforts to control them have not been so well funded. However, since the beginning of this decade coordinated initiatives to improve this situation suggest there is some light on the horizon.

The Lancet reports that on April 2nd 2014 a meeting took place at the Pasteur Institute, Paris, to release a report from the informal group, Uniting to Combat Neglected Tropical Diseases, a global movement of people and organisations committed to combating 10 NTDs. The report details progress made in 2013 towards the commitments identified in the 2012 London Declaration to control, eliminate or eradicate 10 NTDs by 2020. These are: leprosy, sleeping sickness (African human trypanosomiasis), blinding trachoma, Chagas disease, soil transmitted helminths, schistosomiasis, visceral leishmaniasis (VL or kala-azar), onchocerciasis (river blindness), lymphatic filariasis, (elephantiasis) and guinea worm disease.

A previous Bugbitten blog highlighted progress towards the eradication of guinea worm disease and in April the Carter Centre recorded a 73% reduction in reported cases worldwide since 2012, with only 143 cases remaining in 2013. This is by far the leading NTD in this quest for eradication and it is set to be the first human parasitic disease to be eradicated.

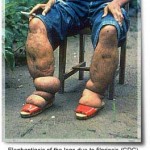

Very encouraging progress is also being made in the fight against two NTDs caused by filarial nematodes. These thread-like roundworms are transmitted to humans via the bite of their insect vectors; mosquitoes or blackflies. Elephantiasis, also known as lymphatic filariasis, is caused by worms such as Wuchereria bancrofti whose adults

live in the lymphatic nodes. They block the flow of lymph, causing oedema (swelling), particularly to the lower limbs and groin area. After mating the females produce microfilaria that migrate into the lymph channels and blood vessels where they can be ingested by a mosquito when she blood feeds. These larval stages develop in the muscles of the mosquito before migrating to its head, ready to move into a new human host when the infected mosquito takes its next blood meal.

Other filarial nematodes cause subcutaneous filariasis, so called because the worms live in the

fat layer beneath the skin. One such worm, Onchocerca volvulus, causes onchocerciasis, also known as river blindness because of the symptoms caused by the parasite and the locations in which it is transmitted. The blackfly vectors (Simulium species) of this disease breed in fast flowing streams and rivers. Infected blackflies transmit the filarial nematodes when they bite people in the vicinity of their breeding ground. Adult worms reside in nodules under the skin where the females produce thousands of larvae. These larvae migrate to the skin, where they cause intense itching, and to the eye, where they eventually cause blindness.

The World Health Organisation’s weekly epidemiological record for 11th April 2014 reported on the current status of these two diseases, as discussed at a meeting of the International Task Force for Disease Recognition (ITFDE). In 2011 this organisation concluded lymphatic filariasis could be eradicated in Africa by 2020 if mass drug administration (MDA) and the mapping of cases could be speeded up, but, elimination of onchocerciasis was more of a challenge with respect to strategies for MDA.

Currently, elephantiasis is prevalent in 33 African countries with people in Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Ethiopia most at risk. Likewise, of the 27 African countries where river blindness occurs, these three countries also pose the greatest risk of infection.

The WHO epidemiological record reports that the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control has shifted its objective from control to elimination and 5 African countries have national programmes for onchocerciasis elimination in place. Nigeria, the country with the highest endemicity of both Onchocerca and Wuchereria, aims to eliminate both diseases by 2020.

Mass administration of the drug ivermectin has given good value for money and is helping to eliminate poverty caused by economic losses in villages were many of working age are blind. However, ivermectin only kills the microfilaria and new drugs that kill the long-lived adult worms are required. The issue of when to discontinue annual mass administration of the drug is also an issue in the face of adults worms that can live for about 14 years. It was also reported that treatment for lymphativc filariasis is lagging way behind that for onchocerciasis but, unlike the day-biting blackflies, transmission by mosquitoes will be reduced by increasing the use of insecticide treated bednets to interrupt transmission by the mosquito vectors at night.

The International Task Force for disease eradication conclude that there has been significant progress towards elimination of river blindness and elephantiasis in the last 3 years but the delay in reporting authoritative annual statistics for these diseases is hampering the planning of elimination programmes. Included in their recommendations is a need for accelerated mapping of these diseases, the integration of these control programmes with those for malaria elimination and the development of better diagnostic tools.

Another addition to the rise in interest in NTDs is a United Nations backed initiative, set up in 2011, that connects partners with interests in combating NTDs who are willing to share compounds and knowledge with researchers. On 24th April, this UN World International Property Organisation announced that it now has 50 partners in the consortium.

Finally, as many NTDs are transmitted by insects, it is fitting that the 2014 World Health Day was devoted to raising awareness about vector-borne diseases.

One Comment