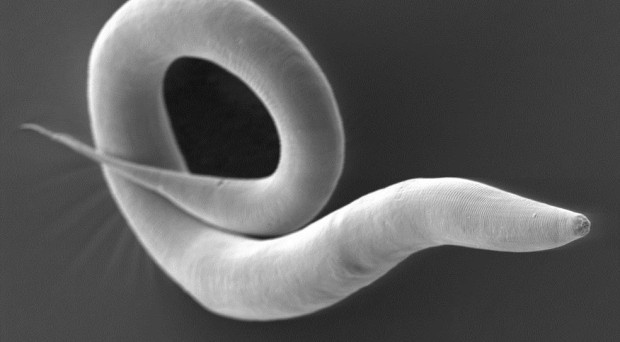

It is one of the most intensively studied organisms in biology: a tiny worm of only about one millimeter in length, more specifically called the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans.

During the last 50 years, this worm has been studied in almost all biological disciplines – with the major exception of one field, namely ecology. It is only very recently that the natural habitat of this nematode was investigated in more detail and our understanding of the worm’s ecology is still poorly understood.

Small animal, vast distances

In our current study, we were initially interested in understanding how very small and rather immobile animals like nematodes can cover substantial distances between spatially separated habitats. One likely strategy is to hitch-hike on larger animals including, for example, slugs. They indeed do so, but in a manner that had not been expected.

My group discovered that C. elegans is able to survive even inside the body of the slugs and apparently uses this option to travel from one habitat – a food source – to another. For example, several slugs of the Arion genus and three other slug species are used by nematodes for this kind of transportation.

Surviving inside the slug

Most surprisingly, the worm seems to proliferate inside the guts of slugs. This is unexpected because it implies that the nematode is able to cope with the very hostile environment of the slug’s intestine, suggesting that it evolved mechanisms to protect itself in this milieu.

Moreover, this finding additionally suggests that the worms are able to feed on the slug intestinal microbiota, likely influencing the composition of the microbial community with possibly detrimental effects on the slug. Consequently, our findings may indicate that C. elegans is expressing first steps towards a parasitic lifestyle.

Addressing the nematode’s ecology

These previously unknown findings on a possible new lifestyle expands the understanding of C. elegans’ natural ecology. In fact, almost all previous research with this nematode was performed under rather artificial conditions in the laboratory.

This study represents one of the few that directly addresses the nematode’s ecology. Based on these findings, new research programs can now be directed at the nematode’s biology and gene function in a more meaningful ecological context.

Comments