BMC Health Services Research

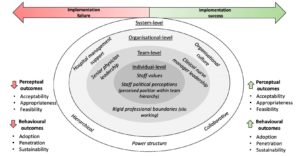

The micropolitics of implementation; a qualitative study exploring the impact of power, authority, and influence when implementing change in healthcare teams

How can healthcare implementation be understood through a political lens? A study by Rogers et al. explored the effect of micropolitics, the use of power, authority, and influence, on implementation processes in the healthcare context. Because of the multidisciplinary nature of healthcare teams, healthcare professionals have discipline-specific priorities and expectations. Thus, multidisciplinary teams must reach agreements in spite of their divergent organizational priorities. Rogers et al. sought to address how micropolitics influences implementation processes by utilizing a multiple case study design and a theoretical framework.

The qualitative analysis revealed that implementing change is an inherently political process in the healthcare context. Hierarchical systems were exemplified in both case studies; however, the impact of the hierarchy differed across settings. The first theme of the micropolitics of implementation was utilizing the hierarchy to exert influence. The physicians were identified as important “role models” in implementing change. Senior managers served similarly to senior physicians, though their role was perceived to have less influence on staff engagement. Additionally, clinical nurse managers played an important role as the “middle-man” to liaise between the disciplines. In one instance, the clinical nurse manager’s rejection of the intervention led to a lack of information amongst the team, negatively impacting implementation. In each instance, the hierarchy structure impacted how team members related to the intervention.

Teams often described a culture of “put up or shut up”. Staff articulated how the hierarchy made them feel “constrained” and “beaten down”, ultimately leading team members to fear expressing their personal opinions regarding the intervention.

The second theme that emerged was how traditional power structures constrained implementation. Teams often described a culture of “put up or shut up”. Staff articulated how the hierarchy made them feel “constrained” and “beaten down”, ultimately leading team members to fear expressing their personal opinions regarding the intervention. Furthermore, the hierarchy of the team impacted how the staff viewed the intervention relating to their influence on the decision. While some staff felt the intervention offered them an opportunity to participate as members of the team and to “have a voice”, which led to more consistent attendance throughout implementation, other members felt the implementation was irrelevant to their role, resulting in poor adoption of the intervention. Finally, silo working, or working in isolation rather than collaboration, negatively affected the dissemination of information within the medical team, limiting engagement. Thus, the hierarchy also impacted cross-disciplinary interactions.

These findings ultimately apply the micropolitical concepts of power, authority and influence to the healthcare context in hopes of providing insight on how to develop more appropriate implementation strategies. The thematic analysis and knowledge of the “everyday politics” of healthcare will certainly help develop a framework for successful implementation.

Defining culturally safe primary care for people who use substances: a participatory concept mapping study

In the midst of the global opioid crisis, developing safe care parameters for people who use substances is essential. Urbanoski et al. conducted focus groups with a variety of individuals who use or used substances, focusing on the patient perspective of safe primary care.

“I would feel safe going to the doctor if…”

Participants were recruited from peer-run organizations that provide support and advocacy to people who use substances. Participants were an average of 42.5 years, half identified as female and one quarter as Indigenous. Following several rounds of focus groups focused around the statement “I would feel safe going to the doctor if…”, the participants produced a cluster map as a “comprehensive and meaningful” representation of the data. The clusters can be summarized as the following:

- Act to prevent stigma: Don’t treat me like crap! This cluster deals with the external and internal stigma associated with substance use.

- Hey I’m human. Treat me right! Similar to Cluster 1, this cluster reflects the importance of humane and compassionate care.

- Uphold professional standards. Cluster 3 primarily focuses on professional competency, particularly around pain management and how providers can recognize patients’ experience of pain as legitimate.

- Do you care about me? How can physicians develop trust with their patients? This cluster speaks to the importance of personalized care, continuity of care, and developing rapport.

- Maintain my confidentiality in a welcoming and comfortable environment. Cluster 5 articulates concerns around the waiting room environment and clinic practices. Participants described crowded waiting rooms and limited privacy in conversation as chief stressors.

- Be a champion for advocacy. How can primary care providers address issues of accessibility and support to improve perceived safety in accessing care? Cluster 6 states examples such as allowing the presence of advocates or friends at appointments, providing care in discrete locations, etc.

- Acknowledge and accommodate my needs and circumstances. Cluster 7 identifies how circumstances impact plans of care. Participants indicated the desire for increased forgiveness of missed appointments, understanding fear of being criminalized for the disclosure of drug use, and more. Each of these statements asked primary care providers to recognize the “structural conditions” that impact accessing healthcare.

- Don’t red flag me: Recognize addiction as a health issue. The final cluster addresses how a physician’s view of addiction as a health issue, not a criminal behavior, helps people who use substances feel safe in seeking care.

Ultimately, these focus groups provide a starting point for improving the delivery of compassionate primary care to people who use substances. This model provides concrete, patient-centered suggestions for improving primary care processes.

BMC Endocrine Disorders

Impact of malnutrition on systemic immune and metabolic profiles in type 2 diabetes

Nutrition has a large impact for diabetes patients and can be linked to managing the condition. Typically associated with overweight or obese patients, this condition is being tracked within malnourished populations and how it affects the individuals’ immunological and metabolic profiles.

It was found that people with a low BMI, or those suffering from malnutrition, had decreased levels of glycemic, hormonal, and cytokine parameters and were therefore less likely to be able to manage Type 2 Diabetes.

Malnutrition has been linked to negatively affecting the immunology of a patient and increasing their mortality from infections. It was hypothesized that a low BMI alters the pancreatic hormone, adipocytokine, and cytokines in Type 2 Diabetes patients, resulting in an increased risk for a more severe form. Covering 88 participants, this study found strong links to BMI and immune response.

It was found that people with a low BMI, or those suffering from malnutrition, had decreased levels of glycemic, hormonal, and cytokine parameters and were therefore less likely to be able to manage Type 2 Diabetes. Consequently, BMI was also associated with the immunological parameters of patients, with normal BMIs having a significant positive correlation for immune response.

BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies

Do women who consult with naturopaths or herbalists have a healthy lifestyle?: a secondary analysis of the Australian longitudinal study on women’s health

Many Australians report that they consult naturopaths, but what does this mean for their health? Steel et al. evaluated the relationship between health behavior and consultations with naturopaths in Australian women among three age cohorts (19-25, 31-36, and 62-67).

Through analyzing the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH), they found that women of all cohorts who had consulted with a naturopath in the last 12 months were less likely to smoke, more likely to report at least moderate levels of physical activity, and more likely to have a vegetarian diet. Additionally, women who had consulted with naturopaths were also more likely to have used marijuana or illicit drugs in the last 12 months.

Further research is needed to understand this relationship between naturopaths and health behaviors, but this study uncovered opportunities for naturopaths to support health behaviors and minimize risky behaviors.

BMC Genomics

Competitive mapping allows for the identification and exclusion of human DNA contamination in ancient faunal genomic datasets

Unjumbling contaminated DNA in ancient specimens pose issues for cost-effective sequencing and interpretation. Identifying the contamination between human and faunal DNA has the benefit of being able to affect analyses when mapping the reference genomes.

This work focuses on the most effective method to competitively map human contamination from ancient faunal DNA with reduced losses of data, thus acting as a beneficial tool within ancient DNA research. This was achieved through the sequencing of genomic data from 70 ancient and historical mammalian specimens, including an ancient favorite: the wooly mammoth.

BMC Medical Research Methodology

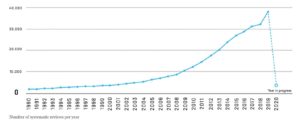

Epistemonikos: a comprehensive database of systematic reviews for health decision-making

Systematic reviews are arguably the most robust form of research evidence. However, as the literature becomes continually more saturated with these reviews, it is more difficult to identify relevant reviews addressing specific questions. How can the scientific community keep up?

On behalf of the Epistemonikos project, Rada et al. developed a database called Epistemonikos of more than 300,000 systematic reviews, making it the largest database of its kind. The included reviews were selected using a machine-based approach, which were then validated by a network of over 1000 collaborators. This database is a free, multilingual, and quality-checked “one-stop shop” for systematic reviews.

BMC Research Notes

What is the size of Australia’s sexual minority population?

Australia’s sexual minority adult population (LGBTQIA+) are difficult to estimate as the Australian Bureau of Statistics does not publish or collect any data on sexual identity. Therefore, this work attempted to provide this estimate and fill the gaps in the latest census data.

Combining data from multiple national surveys and population data, average prevalence rate produced an estimate of Australia’s sexual minority population – utilising data from the General Social Survey (GSS) and the Household, Income And Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. It was found that Australia’s sexual minority was higher in the younger population and steadily increased with surveys conducted in later years.

It was found that Australia’s sexual minority was higher in the younger population and steadily increased with surveys conducted in later years.

Proposing a potential cohort effect for this trend, it is suggested sexual identities can be influenced by social attitudes and the legal environment of the time. Younger cohorts have spent their formative years within a time of higher acceptance of sexual identity and the willingness to disclose one’s identity. This cohort effect has the potential to impact future population surveys and the percentage of Australia’s known sexual minority population.

Comments