Integrated care is characterized by a proactive and person-centered approach to care, which is seamlessly coordinated across multiple professional disciplines and care interfaces. Integrated care aims to improve outcomes such as functioning, quality of life, and quality of care. The organisation of integrated primary and community care is considered an essential step towards supporting older people to age in place.

Maintaining people’s safety at home

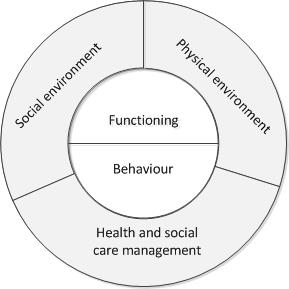

To support older people living at home, it is essential to maintain their safety. Older people encounter limitations in multiple domains of life, which could pose risks to their ability to live safely and independently at home. Such risks may relate to different factors, including people’s functioning and behavior, their physical and social environments, and the health and social care they receive. This wide range of risks could lead to a multitude of problems that challenge people’s safety at home, ultimately resulting in emergency department visits, (re)hospitalization, institutionalization and mortality. Given its proactive, interdisciplinary and comprehensive character, integrated care is expected to provide opportunities to address the prevention of such risks.

Our recently published scoping review in BMC Geriatrics shows that integrated care programs for older people living at home address a broad range of safety risks. After examining included programs according to the predefined conceptual framework shown in Figure 1, findings show that all programs addressed risks related to people’s functioning and behavior, and several programs addressed risks associated with people’s health and social care management. Fewer programs addressed risks related to people’s social and physical environments. However, as the number of people receiving care and support at home keeps rising, risks related to people’s socio-economic conditions, their home environments, and increasing caregiver responsibilities, for example, are becoming more prominent. Therefore, addressing such risks is important, especially since older people themselves also express their concerns regarding these issues.

Timely identification of risks, combined with relevant clinical, behavioral and environmental interventions and support, as well as care coordination or case management, would enhance care providers’ ability to support older people’s safety at home. Prioritizing such a proactive and multidimensional approach requires combining the expertise of professionals from different disciplines of health and social care. However, our scoping review suggests that these linkages between health and social care are not yet common practice in integrated care programs for older people living at home. Investing in collaborative skills and inter-professional dynamics, as well as addressing financial and organisational incentives for collaboration, are deemed necessary to strengthen these linkages.

Balancing safety, autonomy, quality of care and quality of life

This review showed that integrated care programs can potentially incorporate many ways of addressing and preventing risks. However, it remains challenging to priorities these activities in a way that is meaningful for older people. Adopting a person-centered way of working, in which professional expertise is tailored to people’s individual needs and preferences, is considered one of the core components of integrated care. In this light, it is important to acknowledge that safety is not the only aspect to consider, especially in the care provided in the context of people’s homes. People’s homes are not only care settings, but the setting of their daily lives, and older people may have preferences or make choices that value quality of life over safety. This means that safety risks cannot be addressed independently of older people’s perspectives. Instead, professionals are tasked to consider their professional perceptions in combination with older people’s preferences, and find a balance between aspects such as safety, prevention, autonomy and quality of life.

Truly supporting people to age in place requires a societal shift towards a broader paradigm of health and well-being.

However, in practice, this raises the question of responsibility and accountability for the safety of older people living at home. Naturally, professionals have no control over how older people live their lives and the choices they make. As such, professionals cannot be held accountable for the adverse consequences of those choices. What then, exactly, is the responsibility of health and social care professionals? And what is the responsibility of older people themselves, their families, or society? How is accountability for adverse events shared across these different stakeholders? These questions necessitate a widespread debate on our perceptions and expectations of quality of care, prevention, and ethics, as well as individual, professional and societal responsibility and accountability.

Expanding the health care paradigm

Concluding, integrated care provides both a platform and tools that could be harnessed further to support older people living at home in a manner that balances safety with other values important to older people. However, it is important to note that efforts to integrate health and social care alone are not enough. Truly supporting people to age in place requires a societal shift towards a broader paradigm of health and well-being – a paradigm that recognizes the role that health, social, and environmental factors play in older people’s ability to live safely at home, and in which many different actors in the wider community play their part and perform their responsibilities.

Comments