With consumers now more health conscious than ever before, nutrition food labels are becoming increasingly important to help us choose between products.

In light of recent advances in nutritional science with regards to the link between diet and chronic diseases such as heart disease, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in May 2016 published rules on the new Nutrition Facts label for packaged foods which will facilitate consumers in making informed decisions when it comes to food choice. By January 1st this year, manufacturers with $10 million or more in annual sales must have switched to the new label. Those with less than $10 million in annual sales have until January 1st 2021 to comply.

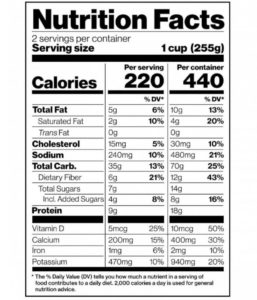

With the new nutrition labeling rules kicking in this year, consumers will be seeing labels which reflect how Americans actually eat. One of the requirements listed in these rules states that the first column of the label must list nutrition information based on the serving size for the product and the second column based on the entire contents of the package.

With the new nutrition labeling rules kicking in this year, consumers will be seeing labels which reflect how Americans actually eat. One of the requirements listed in these rules states that the first column of the label must list nutrition information based on the serving size for the product and the second column based on the entire contents of the package.

Do nutrition labels influence healthier food choices?

There is little information on how food labels are used in real-life shopping situations, or how they affect dietary choices and patterns. It is important for consumers to understand what nutrition claims mean so that informed decisions on product choice can be made, supporting the argument that smarter labels and smarter policies are needed to make healthy eating the cheaper and more widely available choice.

A systematic review recently published in BMC Public Health examined the evidence that nutrition claims relating to fat, sugar, and energy content influence energy intake and food choices. The study’s results suggest that these claims can shape the knowledge of consumers with respect to perceived healthfulness of products, as well as the expected and experienced tastiness of food products. Furthermore, nutrition claims can also make the appropriate portion size appear to be larger and lead to an underestimation of the energy content of food products.

Front-of-package nutrition labeling

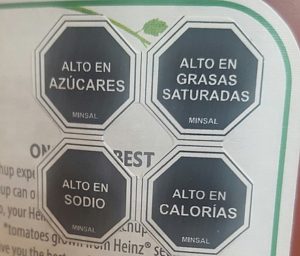

With the increased public interest in identifying healthier foods, U.S. food processors have been adding nutritional  information to the front of packages (FoP) in addition to nutrient content or health claims, a type of labeling also seen in other countries. Examples include symbols that broadly suggest that a food is “healthy,” “good for you,” or “a better choice.” and symbols that purport to list on the front of the packages the key nutrients in that food.

information to the front of packages (FoP) in addition to nutrient content or health claims, a type of labeling also seen in other countries. Examples include symbols that broadly suggest that a food is “healthy,” “good for you,” or “a better choice.” and symbols that purport to list on the front of the packages the key nutrients in that food.

Chile was the first country worldwide to implement a FoP warning label and several countries have followed this model. A study describing the process of development for the Chilean FoP warning label looks at the visualization, understanding, and ability to modify intended purchase of different prototypes of warning labels. A black-&-white stop sign with a simple text indicating ‘Excess of <nutrient>’ was identified as the best option to implement a warning message in the context of the Chilean Food Labeling and Marketing Law. In June 2016, the Chilean government implemented this FoP warning label (amending it to ‘High in <nutrient>’) and several countries such as Uruguay, Peru, and Israel have approved the implementation of warning labels similar to this one.

Research suggests that consumers like FOP labeling, finding it to be a time-saver. In a study published in BMC Public Health, Jorge Vargas-Meza and colleagues compared the acceptability and understanding of labels used in Latin-America among low- and middle-income Mexican adults. The participants were assigned to one of three labels: Mexican Guideline Daily Allowances (GDA), Ecuador’s Multiple Traffic Lights (MTL), or Chile’s Warning Labels (WL) in red. The time participants took to choose the product was measured, as well as the differences in label acceptability and understanding. The GDA, which indicates the grams and percentages (according to the guideline-based daily intakes) per portion of kilocalories, saturated fats, other fats, sugars, and sodium, had the lowest acceptability and understanding among the labels tested. The MTL and the WL were more accepted and understood, and allowed low- and middle-income consumers to make nutrition-quality related decisions more quickly.

Can food labels affect health behavior?

Calorie-only food labels at points of food purchase have had limited success in motivating people to change eating behaviors and increase physical activity. Christopher B. Deery and colleagues set out to examine changes in physical activity in participants exposed to activity-based food labels compared to those seeing standard calorie-only labels in their worksite cafeteria. The results of the study suggest small positive effects for the Physical Activity Calorie Expenditure (PACE) labels on self-reported (~ 20% increase) and objective (~ 6% increase) physical activity. While the overall effects are modest, the results support the need for additional study on factors that may interact with intervention effects. The study also highlights the possibility that women and men respond differently to food labels.

A pilot randomized controlled trial carried out in Singapore used an experimental web-based grocery store to test two FoP warning labels intended to reduce purchases of products high in sugar. The first label is an English language version similar to the one used in Chile, that shows a black stop sign with the words ‘high-in-sugar’ in the center. The second label is a text-based health warning label which is similar to labels considered in several municipalities in the US and also resembles the warning label on cigarettes, but without the accompanying graphics. The text-based health warning label generated a statistically significant reduction in labelled products purchased, suggesting that FoP warning labels have the potential to reduce demand for products high in sugar.

A pilot randomized controlled trial carried out in Singapore used an experimental web-based grocery store to test two FoP warning labels intended to reduce purchases of products high in sugar. The first label is an English language version similar to the one used in Chile, that shows a black stop sign with the words ‘high-in-sugar’ in the center. The second label is a text-based health warning label which is similar to labels considered in several municipalities in the US and also resembles the warning label on cigarettes, but without the accompanying graphics. The text-based health warning label generated a statistically significant reduction in labelled products purchased, suggesting that FoP warning labels have the potential to reduce demand for products high in sugar.

Downsides

Surprisingly enough, nutrition claims labels may also be used to falsely give the impression that a product is healthy.

The WHO 5-a-day fruit and vegetable (FV) guidelines generally recommend consideration of fruit juice as only one FV portion regardless of quantity, for reasons based on the processing of nutrients and fiber breakdown.

If a product claims to contain two or more portions of your 5-a-day FV, this should come from more than one fruit or vegetable. It should also be ensured that that the serving size is appropriate and the amounts of saturated fat, salt and sugar are limited.

Food product labels which highlight the healthy component of a product can have positive impacts on healthy dietary profiles. However, if the ‘healthy component’ of a product is exaggerated, this could lead to negative effects.

Food product labels which highlight the healthy component of a product can have positive impacts on healthy dietary profiles. However, if the ‘healthy component’ of a product is exaggerated, this could lead to negative effects.

With this in mind, researchers from Bournemouth University carried out a study published in BMC Public Health, which investigated the impact of a ‘3 of your 5-a-day’ versus a ‘1 of your 5-a-day’ smoothie product label on subsequent FV consumption. Using an acute experimental design, 194 participants (90 males, 104 females) were randomized to consume a smoothie labeled as either ‘3 of your 5-a-day’ or ‘1 of your 5-a-day’ in full, following a usual breakfast.

The authors found that exposure to a ‘3 of your 5-a-day’ FV label following a usual breakfast resulted in reduced subsequent FV consumption compared to exposure to a ‘1 of your 5-a-day’ label. This can probably be explained by the fact that consumers felt they had achieved higher adherence to the dietary goal by consuming the product with this label and therefore allowed themselves lower adherence with subsequent FV consumption.

The results of this study indicate the potentials dangers of providing exaggerated information on food product labels with regards to FV provision. Increased regulation may be required to ensure accuracy in these types of messages.

Eating out

As eating out has now become very common, and food served outside of the home is often of low nutritional quality, the FDA also oversees food labeling in restaurant menus.

Although kilocalorie (kcal) labeling of food and drink products sold in restaurant chains in the US is now mandatory, in store kcal labeling practices among major UK restaurant and takeaway chains have not been examined. In August 2018, researchers based at the University of Liverpool contacted, visited the website and/or retail outlets of major eating out and takeaway food chains in the UK, including full-service and fast-food restaurants, cafes and coffee shops. They examined the proportion of chains providing kcal information to customers at point of choice in store and the extent to which kcal information provision adhered to labeling recommendations. They found that it is rare for eating out and takeaway chains in the UK to provide point of choice kcal labeling and when labeling is provided it does not adhere to recommended labeling practices.

Calorie information alone may not be sufficient to motivate behavior change, especially when making a decision at the point of purchase (such as in a fast food or cafeteria line) where distractions and time-pressures are common. Physical activity equivalents provided with calorie information may provide increased motivation for healthier food choice as previous research suggests that calorie information alone may not be sufficient for behavior change. Anthony J. Viera et. al. explored this idea in a study examining the effect of PACE food labels compared to calorie-only labels on point-of-decision food purchasing in three worksite cafeterias in North Carolina. They found that cafeteria patrons exposed to PACE labels during their workday lunch did not purchase any fewer calories than those exposed to calorie-only labels. Future studies in alternative settings, especially fast food restaurants, are called for in order to determine whether physical activity equivalents are a useful addition to existing calorie information in order to provide the extra motivation required to make a healthier food choice.

Calorie information alone may not be sufficient to motivate behavior change, especially when making a decision at the point of purchase (such as in a fast food or cafeteria line) where distractions and time-pressures are common. Physical activity equivalents provided with calorie information may provide increased motivation for healthier food choice as previous research suggests that calorie information alone may not be sufficient for behavior change. Anthony J. Viera et. al. explored this idea in a study examining the effect of PACE food labels compared to calorie-only labels on point-of-decision food purchasing in three worksite cafeterias in North Carolina. They found that cafeteria patrons exposed to PACE labels during their workday lunch did not purchase any fewer calories than those exposed to calorie-only labels. Future studies in alternative settings, especially fast food restaurants, are called for in order to determine whether physical activity equivalents are a useful addition to existing calorie information in order to provide the extra motivation required to make a healthier food choice.

Are you carrying out research on nutrition labeling? BMC Public Health would love to consider your work! Submit your manuscript here: https://www.editorialmanager.com/pubh

Comments