We now know that it is something in the farming environment that makes the salmon there have many spots, but we have yet to find out exactly how the spots are triggered. It could be anything from the lighting regime, temperature, diet, to the fish density or growth rate.

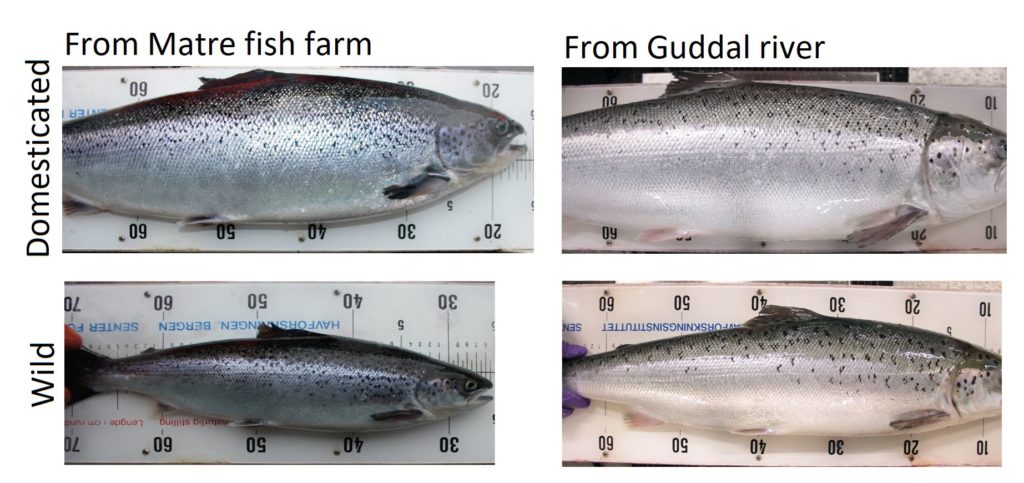

We investigated whether a specific breed of domesticated salmon had different numbers of spots depending on whether it had been hatched in a river or lived on a salmon farm its entire life.

We planted domesticated salmon into the Guddal river, Norway, where it hatched and stayed for 2-4 years before we took the salmon out of the river as smolts (juveniles) and moved it to our research station at Matre. After spending two years in land based tanks there, these salmon were still seven times less spotty than domesticated salmon that had lived its entire life at Matre under standard farming conditions, even though the salmon were the same breed.

Both domesticated and wild salmon growing up in a farm environment had many spots, while all the salmon, both domesticated and wild, that were reared in the river had few spots. This means that we can be certain that it’s the environment that decides how many spots a salmon gets.

However, we also identified a region on salmon chromosome, a quantitative trait locus (QTL), containing genes linked to the degree of spottiness. So, genetics does play a role, but it is small compared to the effect of the environment.

Both the wild salmon and the domesticated salmon from the Guddal river had few spots even though these salmon lived for two years in land based tanks at the research station at Matre. This indicates that the spots were established on the salmon before it was removed from the river at smolting. That the salmon receive their distinguishing marks before they have time to escape is a useful observation.

Many spots are nevertheless a safe indicator of an escaped farmed salmon if you catch one in a river.

Cleaning rivers of escaped farmed salmon currently happens based on visible traits such as body shape, the wear of fins and spots. If farmed salmon survive for long in nature, they start to resemble wild salmon. Spots on salmon have been shown in several studies to be stable over time, so they probably don’t disappear upon escaping, although this is not what we have tested here. Many spots are nevertheless a safe indicator of an escaped farmed salmon if you catch one in a river.

Recently, experiments in Zebrafish show that when their stripes are disrupted experimentally they grow back in a way that is consistent with Alan Turing’s theory of how biological patterns form. Turing patterns are known for allowing the environment to influence the pattern in ways which create individuality in each one – like in human fingerprints. Finding environmentally determined patterns in a well characterized species like Atlantic salmon points to new opportunities for studying biological pattern formation.

Individuality of patterns together with spot stability over time also suggests that spot patterns could be used for identifying individual fish using video surveillance, which may be used to monitor the environment in both fish farms and rivers.

Comments