Personality is one of the most complex and variable traits and describes an individual’s behaviour and habits. In order to measure personality, behavioural traits can be put on a scale, which can range for example from shy to bold, active to passive, or social to non-social; taken together the scores on each scale describe a wide variety of personality phenotypes.

Given that personality defines organisms at the individual level it is generally assumed to be stable across different environments and circumstances, and certain personality traits are inherited from parents to their offspring. An individual’s personality will directly affect its social interactions and is likely to influence its social status. Nevertheless, social rank and dominance are also known to be context-dependent and hence can change rapidly.

In our study we were particularly interested in understanding how such a complex trait as personality is transmitted across generations and how much is actually determined by the parent’s genes and how much is affected by the social status and hence inherited through non-genetic factors.

The role of non-genetic factors in transmitting environmental conditions experienced by the parents to their offspring has gained increasing attention over the past few years. Environmental stressors such as dietary restriction or toxins experienced by males have been of particular interest due to their mostly negative transgenerational effects on a wide range of offspring phenotypes.

In contrast, much less is known about the influence of social factors on offspring behaviour and phenotype as these are often experienced during a limited amount of time. In addition, the role of the father in this context has traditionally been marginalized, especially in situations without paternal care, where males seemingly contribute nothing else but sperm and hence their genes.

However, with the recent discoveries of non-genetic factors such as different types of RNAs and modifications of the DNA that regulate gene expression also in the zygote, this stand has been overruled. Now is the time to look into the consequences of short-term variation in the paternal environment for offspring fitness.

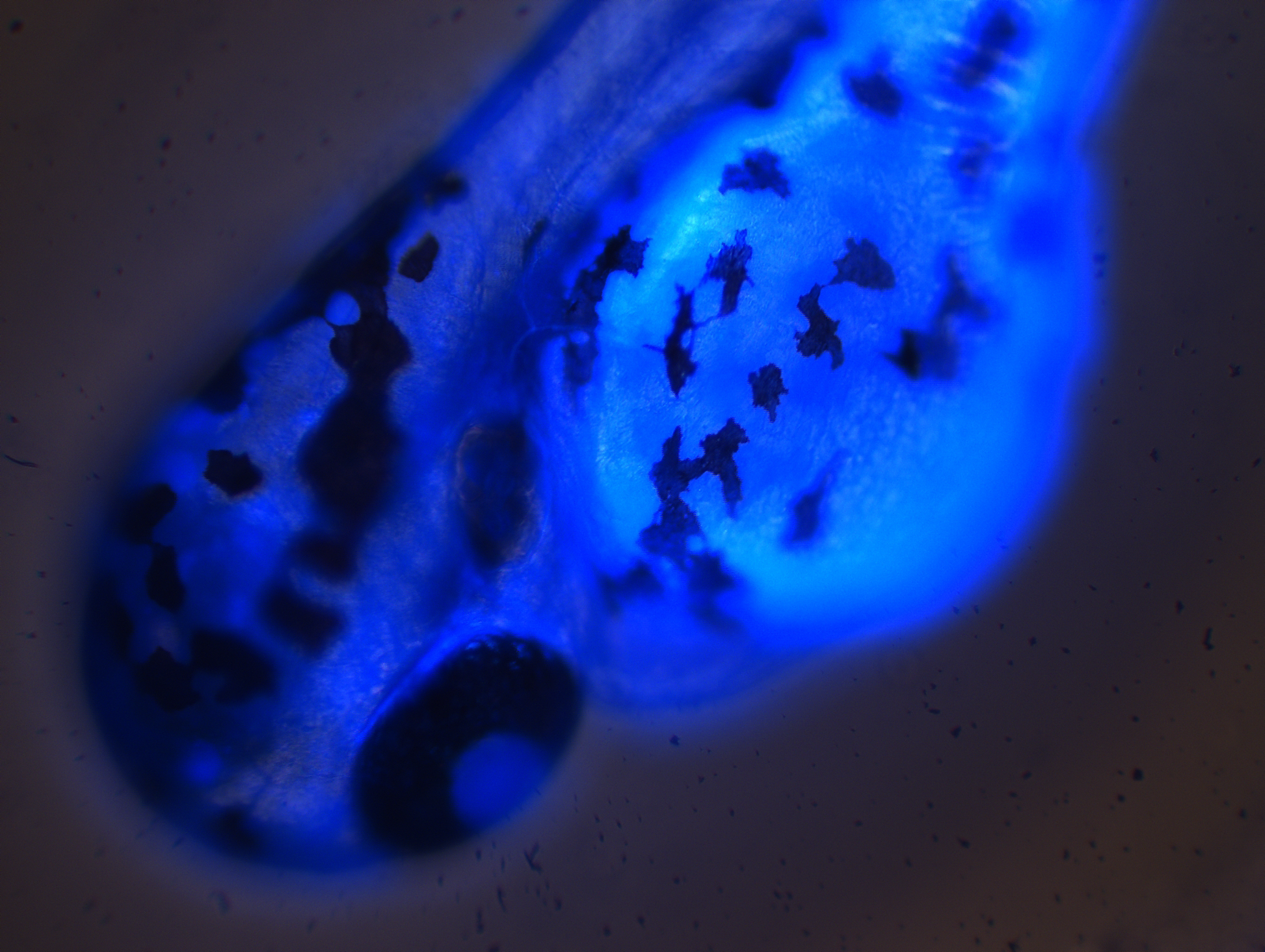

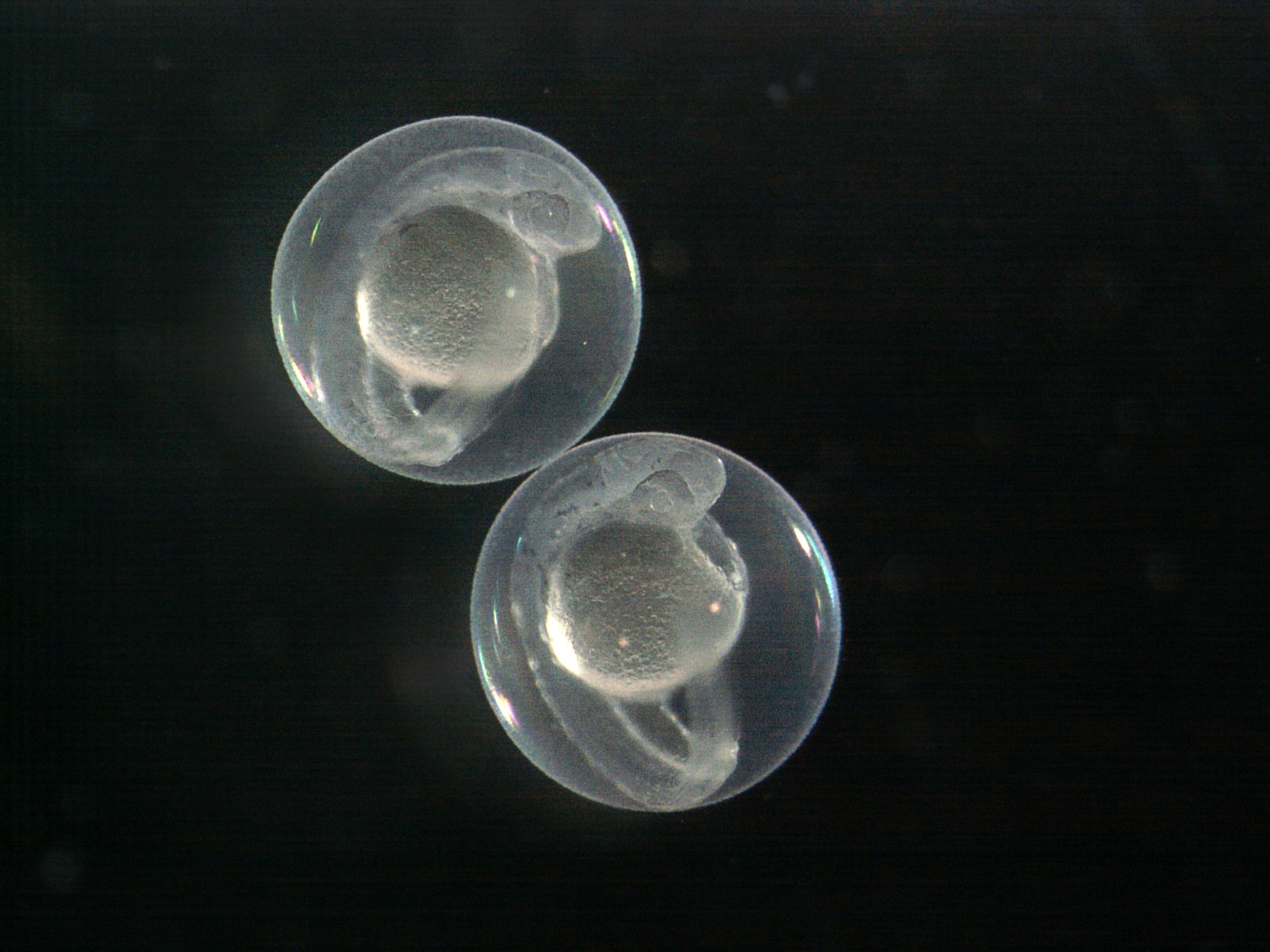

We tested male personality of zebrafish in repeated assays to create an accurate personality measurement and manipulated the social rank among males by forcing dominant males to become subordinate and vice versa. The offspring sired by the males after each of the two rounds of manipulation were found to be significantly affected by their father’s personality as well as his current social status. There was no indication for a predictive relationship between personality traits and initial dominance status, but personality traits were relatively stable across time and across manipulation periods.

We used in vitro fertilization assays and a split-clutch design to account for paternal and maternal individual differences. The most marked differences occurred in offspring sired by fathers that were forced to change from a dominant to a subordinate status.

The fact that we found a significant influence of the father’s social environment as well as his intrinsic personality on offspring performance supports the idea that an individual’s behaviour is determined by a complex interaction between its father’s genes and his social status.

Comments